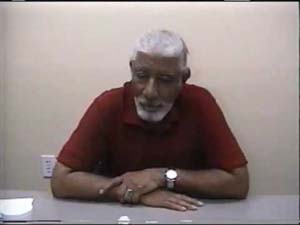

9/25/2003 Val Archer interview, Atlanta History Center He is president of the Atlanta chapter of Tuskegee Airmen Veterans group. Transcribed 10/2003 by Frances Westbrook. NOTE: I have not tried to check spelling of the military bases he mentions. Interview with Mal Roseman, volunteer from the AARP. Side 1 MR: I'm Malcolm Roseman in Atlanta, Georgia, on September 25, 2003. I have the honor of speaking with Val Archer, also from Atlanta. Val, let's begin by just telling me where you were born and when, and a little bit about your early years. VA: OK. I'm Val Archer. I was born in Chicago, Illinois, on my grandmother's birthday, in 1929, on April 13. I attended elementary school at Betsy Ross, and I recently heard in the news it's still around and having probably more difficulties today than they were having then. As my family moved from one neighborhood to another, I transferred to different schools. I eventually graduated from [summer?] school, at a school called Charles Cominsky[?], which was over on the far east side of Chicago, I believe, from the 8th grade. I didn't go to high school, sort of dropped out then. My mother passed when I was 12, and I guess I didn't have the type of supervision that was necessary to compete with my peers at that time. My environment. I joined the service in 1945. Because I was out of school I associated with some fellows who were a few years older than I, and I sort of followed them when they went into the service, and it was my plan to follow them, and so on. MR: You were quite young when you went in. VA: Yes, I was. But I was sort of caught up, as I think many people were, with what we know as propaganda now, the way the war was described through the mass media and throughout the community, in every kind of institution. We were sort of bombarded with information about the enemy and the Axis and so on, and Uncle Sam needs you, and the USO, and the news reels, and so on. And in my young mind, I was caught up very much in that. And I figured that, I think I estimated that since I wasn't very productive at that time in any case, being in the military service would not be a bad thing for me. So I tended to follow in the footsteps of some of the older guys and I tried to enlist. I think, first in the Marine Corps and then the Navy and then the Maritime Service. And that went on, in fact, for a couple of years. And, one day another, a friend of mine and I were passing a recruiting station and decided we'll just go in and heckle these guys, ‘cause they're not going to take us anyway. As it turned out, I think, on that particular day, I've since deducted that probably that recruiting sergeant didn't have his quota at that time, because Freddy West and I both wound up being processed straight through, and finally loaded onto the back of a six-by-six and shipped out to Fort ____, Illinois, where we were inducted and sworn in and so on into the service. From there, it was a short trip, a short time before moving on into basic training in Wichita Falls, Texas, and so on. My early years in Chicago, I think, as I look back, everything seems to be sort of normal in my own terms. Perhaps it would not be normal for someone else who was observing that as I observe young people today. Some of their experiences are extraordinary and I think probably some of mine were as well. I had two brothers and one sister. One of my brothers recently passed a couple of years ago. Both my brothers sort of followed me into the service. Of course, they went to high school and graduated. MR: Were you the oldest? VA: I was the oldest. And ….let's see… MR: Well, let's go back to your military. You're now in Texas in basic… VA: Yeah. As I recall, that was quite an experience. And as I look back at it, some of it, I find some humor in it. Growing up in Chicago as I did, and I had, I did my time with gangs and so on. And as I came into the service I sort of brought myself into that picture and I obviously came into conflict with people from other backgrounds. I recall an incident with a wrestler from Oklahoma who was, I think, I guess he was probably about 200 pounds and I think I was probably about 130 pounds. And one day, he had decided that since our organization at the time was very close to his home, from Texas to Oklahoma was just a short trip for him, he had figured out that if he managed to get our training set back, then he would have an additional amount of time out near home, and so on. So, I thought that was kind of silly and kind of selfish on his part, and so did another kid from Detroit who was probably about my size, who said something to this guy, and he got smacked. And I thought, if he can get away with that, smack this kid and get us to go back and do that, then I'd have to try my luck with him. So, we were on the second floor of this barracks and so almost immediately we were tumbling down the stairs. And that lasted for I think a good 20 minutes or so, maybe longer than that. But I, I rather enjoyed it, and looking back at it, to be bloody or have that kind of physical engagement was not unusual for me. And I think probably fortunately for me it was, because it was not for the wrestler. So we both wound up going to the hospital. And I just always find some humor in that, in recalling that experience. MR: I have to stop you and ask you a question, because I think it's germane. You went into a segregated army, and my knowledge of the segregated army at the time was mostly officers, maybe all the officers that were around, tended to be, they were white. [Yeah.] How did you feel about all that? VA: I guess I had some feelings about it, but as I was incorporating all this new experience, I didn't know anything about, anything about the military, about the officers corps, the enlisted corps, or any of that. That was something that I had to learn. But I very quickly learned that some of our white officers were quite racist in their outlook and their expectations. And with my attitude as I was describing with the altercation with this wrestler, I would have had the same propensity to deal with them in the same way. I guess I was fortunate in a way that I received a few reprimands and had a lot of extra duty but I never punched one of them. And I therefore managed to stay out of serious, serious problems with them. But I fairly quickly became aware of the fact, and it was not, it was a kind of a group learning experience. It wasn't just that I was learning this myself but I was learning it from the other guys who were in the organization, and their attitudes, some of which I adopted, some of which I rejected, and so on. But I managed to keep a perspective over my feelings of individuals that I was involved with, and I met some pretty rotten white officers, and I met some very good officers that I later learned what a good officer was, and how he performed. And I quickly learned the difference, I think. MR: So you did the six weeks of basic? VA: Yeah, it seemed to have been longer than that, but it may have been six weeks. MR: Then what? VA: Well, from that I went to an aviation squadron, that's what they were called at that time, because when I enlisted, I had an opportunity to indicate which organization I wanted to belong to, and I checked the air corps, not knowing much about it other than what some people had told me. And I didn't have any expectations one way or another at that time. It didn't matter which branch you were in, you were still a soldier. And all of the appearances for the uniform and the attitudes and the values and so on were still that of a soldier, which was Army. I later on learned that being a part of this aviation outfit [was different?], though I didn't know at the time that there was an effort to develop this all-black outfit which was still going on since 1941 and 1942. MR: Before you go further, you put that down, to join an air group. Was there something that triggered that thought in your mind? I recognize that they were all part of the Army, and they were all soldiers, but still, I mean, going up in a plane, you know that whole thought, for somebody who grew up in a Chicago neighborhood, that's pretty extreme. I mean, what …. Were you a risk-taker? VA: Oh, big time. Yeah, I would take any risk at that time, although I did not perceive that as a risk. What I knew about airplanes at that time was, now I know that they were DC-3's that used to fly very low over Chicago, and you would hear them comin' for days. And of course by any stretch of the imagination they were slow, you know, because you could see them if you were in an area where the buildings were not very tall, you could actually see this DC-3 just flying over on its way. And I thought, boy, that would be great to do that. My exposure to anything to do with aviation was kind of fantasy stuff that I read in comic books and I think there was a radio serial at that time, I think it was Buck Rogers in the 25th Century or something to that effect. And that was sort of, I read a lot, and that was one of the things that I knew just a little bit about. So, when I had a choice of being in the army, I thought, OK, marching, carrying a weapon on my soldier, or flying in an airplane, whatever they did in the airplanes, I didn't know anything about fighters and bombers and stuff like that at that time. But I thought it was a pretty good choice. And I really didn't expect to get it, I just thought, OK, I'm going through this stuff. And I was psychologically geared to a kind of a racist culture that I could not articulate at that time. But my expectations were that, you're going to get the short end of the stick anyway, so just put down whatever you think you can get away with it, and go for it. MR: All right, so you moved into this, to where, at this point? VA: My first stop after basic training at Wichita Falls, Texas, was a place called Geiger Field at Spokane, Washington, and I went there. That was a fairly pleasant experience, you know, being out of the city, and out of Texas, which is another world by itself. To go up into the mountains, and it was cold and pristine, and a new experience, and I was excited about it. I went to, I think it was a demolition school, to learn how to blow up stuff, which was not inconsistent with my character at the time. But when I completed the training, I was very quickly put on a train with orders going to join this 332nd fighter group in Columbus, Ohio. And that's where I went to spend the next, a little more than three years until the integration occurred. MR: And so, you were in Columbus, Ohio, for three years at that point? VA: That was my base. Of course, I left here for training at different places, at Chinault [sp?], Scott, Keesler, Mississippi, short training. MR: At least for the World War II piece you were always in the states, you were stateside. [Yeah.] What were you trained for in Columbus? VA: Well, when I got to Columbus one of the first assignments that I had was as, to work on B-47s as assistant crew chief. And initially I was a gofer but that was called on-the-job training or OJT, which I became involved in. First in aircraft engine mechanics, and then I sort of gravitated to instrument specialist, where I worked with the instruments and related component parts like the—the instrument doesn't operate just by itself, it operates on some principle that's related to something else. Like the air speed indicator for example. In those days we had what was known as a peto-static tube [?] where that would register the pressure of the forward motion and that would be registered into this air speed indicator that would do that. Then there were engine instruments, manifold pressure gauges and tachometers and indicators and so on. MR: At this point, you were 17, 18, 19 years old…. VA: 16. MR: Even younger. 16, when you first went in. You never went to high school, here you are getting a whole education. How did you feel about all that? VA: I thought it was a real challenge. I enjoyed every minute of it, including all the other altercations that I got involved with. The thing I did not enjoy is I did an awful lot of KP, washing pots and pans, reporting to that at like 3 o'clock in the morning and working on that until 7 or 8 o'clock at night before, you know, getting off. MR: They taught you discipline. VA: Yeah. I can tell you some stories about [laughter]. I had some pretty creative first sergeants. But I managed to not spend a lot of time in the guard house. I did get to know most of the guys over there on a first name basis. MR: Well, we don't need to go into all the details on that… VA: No. MR: Tell me, so you were in Columbus for the most part until 1948? VA: '48…'49. MR: '49. Now, I believe Truman integrated the services in… VA: '48. MR: '48. How did that affect you? VA: Well, that, in terms of segregation, that really brought that home to me. You know, from my growing up in the civilian community was in Chicago. And it was not like growing up in Georgia or Mississippi or someplace like that, so I had a whole different kind of learning thing to get a grip on. It occurred to me when I left this all-black outfit, that was the only kind of military experience that I was aware of. In fact one distinction we briefly mentioned earlier about the white officers corps, when I finished my training and went to Lockborn, that was the end of my white officer experience. Our officers were all black, and in my estimation, far more professional and qualified in every way than those white officers that I had met prior to that time. And they were good mentors. Some of those guys I met back in those days who decided that they would take an interest and teach me some lessons, which they did, a lot of them, I still know those guys who are still surviving. And we can recall some interesting experiences from those days. But as far as the integration was concerned, that was my first experience with segregation from a different sense, because I was moving from an all-black community that had its own social and political and other kinds of dimensions into an all-white installation where there may have been 2,000 white troops there and three black troops. The black troops who were already serving on those installations were in the food service jobs and motor pool and what were considered unskilled jobs at that time. Now when I hit, my first assignment was at Bowling Field [?], headquarters of USAF. And when I reported in there, although I'm sure it was well publicized that, you know, you're going to get some black troops coming in here, and probably that they are skilled and qualified people, when I went to first report in to the flight line, I was told, well, I was a sergeant at that time, and I was told that, well, you can't supervise anybody here, we can't have you supervising any white troops, so we'll have to find something else for you to do until we get a white person who will come in and be over this shop, or this position. So I wound up being sent off to tech school, and spent more time in tech schools, and then I decided I would try and play football there, although I didn't weigh very much, but I was fast and I liked the game. So I did that for a season, in fact I did that until the Korean War. My first experience, initial, with that was, I had orders to go to Korean on assignment. And I was shipped out to a base, point of debarkation I think it was called in the San Francisco area, it was an Army base. And when I got there, I stayed around with a bunch of other guys who had come in from different places, and we were going to be on this joint assignment, I guess, leaving together anyway. MR: The war in Korean had already begun? VA: Oh, yeah. And so while I was there waiting for my direct orders, saying ok, you report to this base, I can't think of the name of it now, and then with further travel to…either K-6 or K-9 or something like that. In any case, when we finally got our orders to move out and board the ship, I remember that the name of the ship was the General Altman, which was a troop carrier. I wound up on this thing for, I think for about 30 days we were on that boat, just weaving in and out of the Pacific, sick as a dog. But we were told that that was necessary and the reason that you're going on this route is because of submarines and you know the whole, kind of scary stuff. In fact, what happened was that I wound up being dropped off on an island after we left Wake Island and we went to Quadulan [??] and then from Quad another few days after that wound up at Antiretoch [?], which was another island in the Marshall Atoll. MR: This is the first time you've ever left the country, at that point. VA: Uh, yeah. As a matter of fact it was. And I was glad not to have to go in that mode of transportation again. That troop ship, I think we were stacked up about 13 high in this place and you know, it's always the guy on top who gets sick first. And trying to find a place where you can breathe, you know, to get up on deck, that was a whole routine, getting permission and so on. MR: Were you part of a unit at that point, or you were unassigned? VA: I was assigned to a unit and didn't know it. I was assigned to a special task force, I remember that, it was called Task Force Number 3.4.1, was our designation. And I think there were, how many of us, got off, I think there were seven who got off, were dropped off on this island at that time, and the ship moved on and went to its next destination, which may or may not have been Korean, I don't know. But anyway I wound up there and this project turned out to be a nuclear project to test an atomic device, which was a whole other kind of experience. And some of the training that I received there was interesting as well. That whole experience was interesting. MR: When you say training, what were you training for? VA: Well, we were, our mission was to fly these drones through an atomic cloud after the weapon was detonated, and then the drones would come back and be examined, or all the checking that was done. The Atomic Energy Commission guys were there. We had Navy and Air Force, I know were there in this joint operation. MR: Your role in all this? VA: My role, I was assigned there as an instrument specialist. There were two of us assigned to that mission. I'll never forget this guy, a guy named Dolan, a white guy who was a kind of senior instrument guy. He had been, I think Dolan had his 20 years in at that time. And he taught me a lot. The two of us, we, you know when you're on an island that size, and practically nothing to do except work and read and so on, which we all did a lot of, I think. The other thing was to booze and fight. I did a little bit of that. But Dolan taught me a lot about instruments, instrumentation and so on. And we had, through our briefings we had a pretty good idea about testing devices which were going on at that time, mostly [?]. We heard about what was happening in New Mexico, and other places in the States at that time. MR: So, when one of these devices was tested, were you able to at least see the… VA: Well, you could…Understand that the device is detonated either on or near an island called, I think it was ___, I think it was 35 miles from where we were, on _________. That was what the report was, but, yeah, we experienced the whole thing, the detonation from that distance…as I recall our instructions were to lay on the ground. And we had some special eye protection and other stuff and we lay on the ground and covered our face, facing the opposite direction of the blast. I'm not sure that that made a lot of difference, because when it went off it was the most brilliant light, almost like you could see it going through your body and through the ground and everything else. And I'm trying to recall which was, if we felt….the island was sort of moving back and forwards, like that, at least that was the sensation. MR: You felt the pressure from the slight movement…. VA: Yeah. And of course the sound was, I think the sound may have been first, no, I don't know whether the sound was first or the flash was first, from that distance. They were separated by a distinct period of time, and it lasted for quite a while. The detonation was early in the morning, maybe 2 or 3 o'clock in the morning, and so on. And we were sort of experiencing that way after dawn the next day. And then of course we were busy again with our separate operations. MR: How long were you on the island doing this? VA: I think for, it was less than a year, maybe eleven months or so. I recall that it was less than a year. [What next?] Next I came back intact with that organization, for the most part, and I was assigned to Eglin Field to a proof test wing, and when I got back there I sort of picked up right where I left off with the base in Washington. “We don't have a spot for you on the flight line.” And I'm sure I was offered, “Would you like to work somewhere else, would you like another job somewhere?” I recall going off to some more tech school at that time. MR: So you're getting a heck of an education at this point. VA: Well, I got some technical training but it was not really an education. I knew what was going on, it was pretty obvious. No one tried to conceal the purpose or the reason for any of this at that time. I had been to Eglin Field before because while stationed at Lockhorn [?] we had our gunnery training there at one of their auxiliary fields where we went every year. We went to, I think there were several auxiliary fields there, and different years we went to different ones, to do training, you know, for the pilots to go out and get their gunnery stuff in. And, of course, we had to support that, those operations. So I was sort of familiar with that. What really went on at that time was some more, that was my first sort of exposure to the south, and what all that meant in terms of being a black soldier. The segregation, the kind of places that we were allowed to go, when we were permitted to go. I remember going to a movie once in Pensacola and being told that blacks had to go, I think into the balcony, but you had to go up the back stairs like the fire escape, that was the entrance to the [unclear]. And there was a place, kind of like a section of seats that we were allowed to sit in. I think that was the only time I ever went to a movie off base. MR: You're about [19]52, '53? VA: No, this was back in the ‘40s. So when I came to Eglin after the nuclear assignment, I was somewhat familiar with that installation so I sort of knew what to expect there. I did have friends, young friends who were married, that I knew, and in Washington, who were assigned there, and they were living in an area called Skunk Hollow, which was at the bottom end, the swampy end of the base, in segregated housing on base. MR: Now let me make sure I understand this. The Army was integrated but the housing was not? VA: Well, it hadn't caught up, the integration. Well, the integration was going on. What was happening, we had black troops on the same base as white troops. That was the first step of the integration. How it unfolded from there was pretty slow, and in fact that's where the real abuse came, in such subtle and unsubtle ways, like the kind of housing again that my friends lived in. Just because they were married and they were allowed to have their families accompany them, they lived in this area called Skunk Hollow. And there were, I'm not sure what kind of housing that was, exactly. It was like, like shacks, but it was like a community of shacks on this installation. And I remember one family in particular had an infant child and they would, the deer would walk up, you know, they were very sort of domesticated almost. And the baby would crawl around on the ground among these fawns that were out there. But it, you know, was so basic and so crude. There was no, I don't recall what it was like there in the winter, I don't recall visiting them during the winter months, which could be quite cold and damp. MR: What were you doing at this point? What was your role? VA: At that point I was, most of my time was waiting for school assignments, so I had some time on my hands. MR: I have to ask this question, because you're now, it looks like you're making it a career. I mean, at some point in your head, did you ask that question of yourself, “Do I want to make the Army a career?” VA: No. I don't think that was ever really, that came later, much later. And I had, you know, we got…in 1950 unless you were at the point of completing your tour, at some point you got an additional year hung on, it was called a Truman Year. And that was I think because of the Korean War. And so, actually by that time, I think in 1953, I think it was 1953 or 1954, when I had an opportunity to get out, I took it. I separated. MR: 1954. VA: Yeah, I think it was 1954. I think it was after I had gone, I went to, yeah, I went to McGill in Tampa, Florida, to B-47 school. Prior to that I had gone to an ______ course. That was crazy stuff. Back at Chanook. And then I went to another course at Scott Field. I don't know what that was about, I don't remember that. But I came back and was kind of excited about this B-47, which was a whole new system, and jet bombers, and really it was a neat, neat system at that time. But I knew after I finished that, it was going to be some other thing, so I just decided, OK, I'll take my marbles and go home. And that's how I got involved, I think, with the Reserves unknowingly. I was carried on the rolls for the Reserves, although I was given an honorable discharge. And I think I'd been out for six or eight months or so and I got this letter saying that, “Report to…,”some base or something, I don't recall the details of it. But, “You've been recalled to active duty.” And, I thought, well, I've been discharged… MR: And the Korean War is over at this point. VA: Well, yeah, '54, it was over. MR: Eisenhower became president in '52. VA: That's right. So I said, well, it's got to be some mistake, you've got the wrong, maybe somebody else with the same screwed up name or something. And I think I contacted whoever the authorities were at that time, and they said, “No, you've been recalled.” And they didn't explain very much as you know oftentimes bureaucrats don't do. And they didn't feel any compunction about, in other words, you're AWOL if you don't, if you're not here, so you don't deserve an explanation. So my attitude was, Come get me. So then I moved to New York to Brooklyn and worked on the docks for, I think, about a month before, I don't know how they tracked me, but I got a letter again saying, “Report to someplace.” And I left again, and I went to Chicago, and I think I was there for six months or so and I got another one of those. And so I left and went to….I don't think, I wasn't really running from them, but in one sense I didn't feel that I owed them any explanation the same way they didn't feel they owed me one. And so, we were having a little standoff there. Anyway, finally, some really official guys who came, I think, in black suits and stuff, and they said, “You're…we're escorting you to your new assignment.” And they gave me two hours or something like that. One of them stayed and the others left. And then they came back. And so, went off to Mitchell Field in Milwaukee. MR: Before you go on, what year…. VA: This was, I think this was in '55. MR: So, you'd been out for a little over a year. VA: More than that. It must have been '53… MR: That you went out… VA: Yeah. Because it was over, no, it was more than a year, because I was bouncing from…as a matter of fact, Eisenhower was president, I think, then. And I remember how interesting it was that every time you turned on the news for something all you would get is how popular this guy is. And at the same time, you couldn't buy a job. There were people in soup lines, you know, and I thought, “What the hell's going on?” With people starving and they're talking about how popular and what a good job, that I didn't. I was not political at all, didn't have any interest, no knowledge of it and so on. But I did think that was pretty strange stuff. MR: OK, so now you're in Mitchell Field in Milwaukee. VA: Yeah. And I think I was there for a few hours and I met this colonel who also had an attitude at that time. I don't know if somebody had done something to him, but in any case, he had this attitude like, “We don't owe you any explanation. Here are your orders…you go next door and get your orders” or something. And I wound up at Geneva, New York. I forget the name of the base, in the dead of winter. And I stayed there for, I was there for I think a couple of months and there was some question about whether or not they were going to give me a grade adjustment or if I was going to have to be a private, which ultimately was the case. They never gave me a grade adjustment. MR: Because you left as a sergeant. [Yeah.] And then you've coming back as a private. VA: Yeah. So I was told that, that the authority for that whole operation was something called the Universal Military Training Act. And the fact that I was not old enough to be out of that category. Now this is what I was told, and I never got a straight answer about it actually. So it really didn't matter all that much. You know, there was no way I could get out of it without going to jail. And they made that clear. So, I sort of started off all over again. I didn't have to go through basic training or any of that, but I did, I think I was offered a chance to go to be a flight engineer, but without the pay. I would be a private on that. And so I thought, well, that's not, you know, we can do better than that. So, I said, you know, give me, send me somewhere else. And so they sent me to a different school again. I spent a lot of time in tech schools. Eventually, well, let's see, after that I was assigned overseas again. I did a tour on Guam, and from Guam I did a consecutive tour in Japan, and I had some assignments in Korea, brief, TDY periods. And then back to Japan, and I got married in Japan at that time. There was, that was a whole other story, it would take two hours to describe that to you. MR: You met your wife in Japan. VA: Yeah. And then I was assigned from Japan to a missile squadron, ICBMs, 395th Missile Squadron at Vandenberg Air Base in California. There was another interesting place where they were no, there was no housing at that time. I think that was a new base, a new facility, a new program and so on. I was assigned to the Titan. Also on that base we had the Atlas. MR: Now, when you say you're assigned, what was your job with respect to that? VA: By this time, I was in training. My job was, I was an instructor, and I did, mostly management training and then some technical stuff from time to time. But mostly I had an opportunity to work with some of the contractors, like Aerojet General and General Dynamics and so on, at night, learning to write technical data. And so that was a good experience, I had an opportunity to do that for a couple of years. MR: Now what years are we… VA: Now we're in 1958 to 1960, almost 1961, November of 1960, when I got another overseas assignment. MR: But at this point, you're in the Army, I mean, you're, you've kind of made the decision to stay? VA: Yeah. Well, by this time it was dawning on me that I was past the halfway mark for some retirement and I was still thinking that at some point, and I think I had given up on the grade adjustment thing. MR: But you're still very young, I mean you're 30, 31 years old in 1961. VA: Yeah, well, I think I felt pretty old at that time. [laughter] Anyway, I had some good experiences, some good training, military training, I think I was one of the most trained people in the military. And I had the opportunity to move into different career areas and learn that. And at some point I got wised up enough to go to night school, and I continued those, attending night school throughout the period when I was in California and then overseas. And I got my undergraduate degree, my education with the University of Maryland. MR: So, you finished, you got your high school diploma, equivalent [yeah], and then you went on to college and got your undergraduate degree. VA: Well, yeah. I didn't do it in that order. I normally didn't do things in a proper sequence. I was, I think I was on the Dean's List for two years, and someone decided that OK, you have, before you go onto the next category, whatever that is, you have to have proof of your high school stuff. So, I faked it, no one had ever challenged me on that before, and I said, well, I went to the school that my brother went to, in Chicago. And it took them about another semester to catch up with that, and they said, Well, they don't have any record of your attending there. So then I was given the option of taking the GED, which I did… MR: You'd been on the Dean's List in college and now you're taking your GED for high school so you can get the piece of paper that says you did it. VA: Anyway, after I left there, that was a long story… MR: Before you go on, what was your degree in, at Maryland? VA: In Maryland, economics and psychology. And that was primarily because at my last year and a half there, because of other people rotating out, and my having the most time remaining there, I became the education officer. So I hired the faculty to teach the off-duty courses for the University of Maryland. And the two best instructors that I had were a young guy, Dr. Lou Everstein [?], who was at Oxford, I think he was doing, he was reading philosophy there, and an economics [instructor] from the London School of Economics. And these were the two best guys that I had. And then, I got another economics professor who had been at West Point, and he was back at Oxford getting his masters in it. So I had these guys consistently over, and… MR: But you're still not an officer. Doing all this and you're not an officer. VA: No. Well, that didn't bother me as much as just not having enough, not having enough money to support my family. But then there were occasions when I had an opportunity to work a part-time job at the Officers Club or the NCO Club, or something like that. MR: But with all this knowledge and background, there was no way of you going into an Officers Candidate situation? VA: No, no way. MR: Was that in part because of the racial issues of the time, or…. VA: Yeah, I think so, because… MR: Even in the ‘60s. VA: Oh, yeah, because I had, I did apply for a program known as Bootstrap, to go away to get your final semester, to get your degree, and that was put off. In fact, when I got my undergraduate degree I was already taking graduate courses. And, because I had more than enough to graduate, except that you had to do one year, your final year had to be at the institution that you got your degree from. MR: So after that, where did you go next? VA: Well, I came back to the states, and I was assigned to Syracuse, New York, where, again, I was the education officer. I didn't have the grade, but I was the only person that they had to do that. And I did, part of my graduate stuff I did at night again at Syracuse. And then I got a fellowship to finish up my masters, and another one to begin my Ph.D. studies. And I was moving, I changed my field from education to political science and public administration. And I wound up with my doctoral studies in inter-disciplinary social sciences shortly after, and I retired there. I put in for retirement in 1968, and at that time I was offered an opportunity, the way it was put to me was something like, If you'll sign on for ten more years, there's this officer program that's in place now. But it was something, the way I understood it was that it was like a ten-year enlistment. You'd sign up for this program and possibly you can come out of it with an O-5 by the end of that ten years. And the sales pitch was, well, look at what you'll be earning ten years from now, compared to what you're doing now. And I had, fortunately I had some good counsel at the university and they said, well, that would be peanuts compared to what you might earn if that's the only consideration. MR: Now, in '68, Vietnam's obviously going on. Your involvement at all?….You never went over there? VA: Just TDY, temporary duty. I had gone over for, I went over for, well, a classified thing for, just for a month, less than 30 days. In fact, I did sign up to go there, to put in a tour, and there was no opening for my career field at that time. And I wasn't serious enough, I wasn't worried about it enough to, you know, to really pursue it. MR: Plus, the war really heated up in '68 when you were really getting out. VA: Yeah. MR: I should shut this off. [They pause to check time remaining on tape.] Side 2 MR: OK. Val, I'd like you to kind of tie together the whole Tuskegee Airmen as it affected you and if you could explain the relationship that you had with it and the benefits and a little bit about the organization. VA: Well, I'm glad to have this opportunity to share some of that. My experience with the organizations that were known, became known, as the Tuskegee Airmen, had—that experience was pretty profound, the impact on me. When I first joined the 332nd and the 477 compadre [?] group at Lo____ in Columbus, Ohio, I was just briefly removed from the whole different perspective and direction that my life was taking. I think that my experience at that installation was probably the most profound in my life because it has influenced the direction that I've taken since that time. To share a little of the background of that organization, it's important to know where they came from, to know where I come from. At that time, I quickly learned that this was a unique organization, it was the only black organization in all of the military services at that time that were engaged in actual military aviation, flying airplanes and everything that goes with that, the entire operation, the entire support function, ground support, operations support, everything. It was like a black city. It had all of its own resources, and all of its own specialists, who performed all of their activities. In my brief experience in the military at that time, that was the organization that had all black officers. We didn't have a single white officer on that installation. I think perhaps there was an occasional TDY person there, but not assigned. What some of those guys went through, they shared with me in a very positive way. The experiences that they had, the frustrations that they had, being trained to maintain the airplanes and then to fly them and then the other, for the fighter pilots, that was the first group that began. The Tuskegee Airmen started off as one squadron, the 99th Pursuit Squadron, which later on became a fighter squadron. It was the first black organization, flying organization, to go overseas. That was a real, they faced real challenges just accomplishing that. This was an organization that wanted to get into the fight. They were skilled, qualified, they had met all of the demands and requirements to be engaged in combat, and they wanted to go and contribute their performance to that. It started off, I think, there were five graduates in the first class. And it was headed at that time by ________ Davis, Jr., captain, West Point graduate. ___ spent four years at West Point, his complete tour there, receiving the silent treatment without anyone speaking to him outside of official duties. A guy who had to go and ask permission as a cadet if he could have a meal at the table of other cadets and would have to get permission to sit down. And often, as I understand the story, was not given permission until the meal was over and then it was back into the drill, and so on. So, some of the kind of harassment, the ugly, unnecessary experiences that this guy had there was, created the kind of discipline in him that as he became the first commander of this all black squadron, as the captain, and eventually—his promotions came quite rapidly—to catch up with his classmates from West Point. He graduated in the top numbers at West Point in his class. Despite all of the difficulties that he had there. MR: Was he the first black soldier at West Point? VA: No. No, he was not the first. There were, I can't give you the names right off now, but there were several. His father was the first black general in the Army. And, but that did not ease his path at all at the Academy. Anyway, when he came out of that, the kind of discipline that he had to develop, the kind of self-discipline to move through that experience, made him the kind of commanding officer to take over this first black flying organization. Now, to get his training along with four other guys who graduated from that, I think there were more than that but I don't have the numbers at my fingertips. So, anyway, going into taking this organization overseas into combat. And at first the numbers of cadets who washed out at Tuskegee where this training was established, it was the only training station for black pilots at that time. Subsequently, a few years later, when we were given the opportunity to fly bombers, B-25s, we received training from several other different locations at that time, different bases where we went for navigation training, places for gunnery and bombadiers and all the crew places, the different kinds of armament training that was required. And we had people to do that as well. Unfortunately, what happened, at different times we didn't have a home, a home base after returning from overseas. We had people who were assigned to Selfrage Field in Michigan, that was part of the organization. And the reason for these different locations…we had personnel at Walterboro, South Carolina, _____ Field, Kentucky, S____ Field in Michigan, and I think there may have been a couple of others. Until we all finally wound up with a base, a home base, at Columbus, Ohio, which was Lockborn. And that's when all the components from different places would pull together. Freeman Field in Indiana, there was a very famous incident there where the base commander, in order to prevent the blacks from using the Officers Club, designated all the black officers as trainees and then established the order that trainees were not permitted to use the Officers Club. And there was a, like a sort of mutiny. What happened was that 101 of these guys decided that they would not comply with that order. They went into the Officers Club. And they were threatened with court martial if they did not comply with that order. The last guy who was finally exonerated from that, and at great personal sacrifice to his career, both in and out of the service, received, I forget the word for it now, but President Clinton forgave his court martial. MR: So, were 101 actually court martialed? VA: Not all of them. But some, as a result of that, though, many of them decided that, OK, I will not remain in the service, because this is already on my record, I'm not going to go anywhere, every opportunity that would accrue would be put down by this court martial thing that was considered to be like a mutiny. We still have at least one of those guys right here in Atlanta, in the Atlanta Chapter. But the kind of discipline that we had to develop, and in my relationship as I came along and joined this organization at the time that I did, and with the experience and everything that was going on in their environment and their lives at that time, was a kind of conditioning process. And for those of us, the black troops who were brought into that organization, we were just sort of sucked into it. And fortunately for us, for the most part, these guys were smart enough and dedicated enough so that they said now, the training that they passed on to us, is that you better not fail at anything. If you fail, we're going to take care of you. And it's going to be worse than [laughter], and I think we got the picture. But, it was that kind of commitment, that kind of dedication and sacrifice that gave us the strength I think, that prepared us to go in and integrate this Air Force, this Army Air Corps. The kind of racism that I personally encountered, and I know that other people encountered the same way, was mostly kind of humiliating experiences for the most part. As being abused mostly, well entirely, verbally, of course. In fact there was some stereotyped stuff about black guys being like Joe Lewis, who was in fact a role model in many ways because he was a champion, and we had him to sort of respect, and that kind of thing to look up to. Fortunately or unfortunately, I think we had the reputation of every black guy is a prize-fighter, and you don't want to engage them in physical combat, but you screw ‘em every other way that you can. And there are thousands of ways to express that kind of racism. Most prominently it had to do with promotions, where on any number of occasions I did, and I experienced it with other people, where we would actually train some white troops who came in, and in a very short time they would replace us with the promotions and all. So, that kind of humiliation and not only the humiliation of it, but the actual loss of money, which was important in trying to maintain a family, and after being involved as long as some of us were, you reach a point where you have to, you've got to finish off the job. And that could be anywhere from wherever you make that decision, and depending upon what your circumstances were at that time, anywhere from, say, 10 years to between 10 and 20 years, and that was the time that you had to stuff that stuff up. And that's a long time. And it creates some very powerful feelings, I think, that kind of deprivation and that kind of vicious ugly stuff. MR: So the Tuskegee Airmen organization really becomes your support group. VA: We were our own support group, yeah. And, as important as it was to go out, to move out and turn the entire military around, and that's happened to a very large extent right now, as important as that was, it was done at great sacrifice, at great expense to many people. And I feel abused by that myself to a certain extent. But I think not enough to stop me from where I want to go, my direction has changed. MR: Now, this organization, you are president of the Atlanta Chapter. VA: Right. MR: So, this is an ongoing organization? VA: Yeah, established in 1972 in Detroit. Some of the guys got together, Coleman Young was one of our pilots at that time who got out of the service and developed a political career. It was under his watch as mayor at that time in Detroit where the organization started. Not that Coleman was the leader or the sparkplug for it, but there were many people who came together. In fact, as in the case I think with a lot of military organizations, where there are friendships that go beyond the active duty part, and together they make contributions to their communities. MR: Is it only veterans, or at-home service… VA: No, membership in the Tuskegee Airmen has always been open. Race, gender, it's open to anyone who agrees to work with the directions and the goals and objectives of the organization, which is to a large extent to help young people, especially minority kids get through some of the barriers and meet some of the challenges that they have to meet that many of us have gone through and are no longer intimidated by them. MR: So there are active servicemen part of the organization. VA: Oh, yeah. MR: It's ongoing. How many members are in Atlanta? VA: Atlanta at the moment has about 50 members, which is a very low count compared to other metropolitan areas of similar stature. We should probably have at least 200 members. That will be my primary responsibility. MR: How long have you been president? VA: Three months. MR: Oh, so it's recent. VA: Yeah. MR: I'm going to take you back a little bit. We're going back to 1968 when you left the Army. Let's talk about the rest of, the sequence… VA: Well, you probably recall that in 1968 was nearing the end of a very violent racial situation in the country. At that particular time I was in graduate school and I was teaching some classes while I worked on my doctorate. MR: In Maryland? VA: No, this was in Syracuse. [Oh, in Syracuse, sorry.] And typically on I think most campuses in the country, particularly in large, predominantly white campuses—our numbers, I think there were two other black guys in my graduate school at the Maxwell School at that time. I think we didn't face a kind of discrimination after getting in and being accepted, we had the same challenges as anyone else. But what was going on on the campus at that time, there were militant undergraduate students and they were agitating for their rights and positions. And we had to some extent an intransigent administration. We did not have…I think black faculty at that time were practically non-existent, and trying to adjust in that situation of kind of racial disparities and so on, while the city wasn't burning down around us, it was very close to it. There were riots with the police and so on. While I was attending school before I got my fellowship, I had worked for the city, actually for the mayor on the human rights commission, and so I was sort of exposed to a lot of that. In fact, my physical condition at that time, I was going to school full time and I was working full time, and I was working with the police on one hand, and several other organizations, and also trying to keep the community focused instead of the actual combat and burning the place down. So I didn't get a lot of sleep and I didn't get a lot of taken care of myself at that time. And as a result of that, I wound up having a heart attack. MR: You were young at this point. VA: I can say that now. I feel now I was young, but at that time I felt pretty old. MR: You were forty? VA: Yeah, somewhere about that. MR: In '69 you would have been 40 years old. VA: Yeah, that's right. Well, in any case… MR: The good news is you survived. VA: Yeah, I survived. Unfortunately, I had, I didn't complete my dissertation, which was a real, it seems like I've had two major blocks in my life. I didn't get a commission from the service, and I didn't finish my doctorate. Those are my two huge disappointments in my career. But it's not over. MR: OK, so you convalesced, you got better. Then what did you do? VA: Well, then I was offered another kind of a challenge, to work for the government again, and I took a job as a training officer with the Civil Service Commission. After about a year of teaching, kind of a normal continuation of my management and leadership studies that I taught… MR: Where was this? VA: This was Syracuse, started off in Syracuse, then it moved to New York. I was offered an opportunity to work with the Carter administration on the Civil Service Reform Act, a special task force again, which I did in 1967 [corrects to 1977]. MR: Carter was president from '76-'80. VA: Right. When I completed that I was given an assignment to teach at the Executive Seminar Center at King's Point in New York. I did that for a while and then I was recruited by one of my students to be the director of training for the Department of Defense Logistics ____ Agency. So I did that, and I subsequently had a friend who was at, who did his mid-career training at Syracuse as an O-6, as a colonel. At that time, he got his second star here at Fort McPherson. I had been out of touch with him for a while. And anyway I was offered a chance to come down and work with him on a special kind of efficiency review study that was going on. That turned into another major, major project, designing a new kind of military light infantry division which was, in fact, it's been operational now in, not Vietnam but… MR: Iraq? VA: Iraq, yeah. At the time it was designed to do combat kinds of operations at FORSCOM and Alaska and other places, but the concept was the one that I worked on. And that was with FORSCOM. And I got another offer from there after completing that assignment. And I got some big awards and stuff for that. And I was offered a chance to work with an organization that John Lewis had established, and it was called, it wasn't a Peace Corps, the Peace Corps was a part of it at the time he did it. But it was called…Action was the name of the organization. MR: He wasn't in the government at this point. I mean, was he a congressman? VA: No, you know I'm not sure what John was doing at that time. I think it was before he went into Congress, though. I think he was doing something else. In fact John was, John had been the first director, the first national director, for this agency [unclear]. In any case, I think he was in some political [?] by the time I got there. And I think since it's been converted over to another kind of operation. But it had, it was an all-volunteer agency working with young children and with seniors and communities and so on, directing volunteers. MR: And where was this? VA: Southeast Region, the headquarters was here in Atlanta. MR: Is that how you wound up coming to Atlanta? VA: No, I came to Atlanta to work with Mike Brown out at Forces Command. And then after completing that assignment Mike was shipped out to Germany again and I worked for the chief of staff for a while, and then he shipped out to Europe and I decided OK, there's nothing else for me to do here. So, I took the other assignment. And I retired from that and I just decided I've had enough. MR: And you retired when? VA: Hmm. '89 or '90. MR: I know you have two children. VA: Yeah. Alicia and Portia [sp?]. MR: And they have children, you have grandchildren? VA: Alicia has two boys, Sam and Jack, who are teen-agers. Sam is 17 and a fairly brilliant kid like his mom, but he decided that he's not interested in higher education, at least not at this time. His younger brother Jack, who is very much like Alicia's younger sister, Portia, who sort of decided that he does want an education. And he's preparing, his goal is Yale. And he's in his sophomore year at high school now. He's an A student, and an athlete and a scholar, and so on. MR: They all live in Atlanta? VA: No, no, they live in Brighton, in Massachusetts, right out of Boston. MR: Val, is there anything else you want to add? VA: Well, I have a grand-daughter who's four years old, who's taken over the family. This is Portia's daughter in Rochester, back in New York. One last thing, since I was divorced and married again, I have a wife here, Victoria, and I'll say 12 years to be on the safe side in case she's watching this. [laughter] MR: OK, Val, it has been a pleasure speaking with you. Thank you very much. VA: Thank you, Mal, I've enjoyed it.