MEN AND THINGS

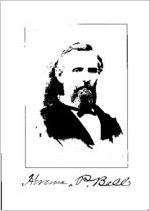

BY HIRAM P. BELL

BEING REMINISCENT, BIOGRAPHICAL AXD HISTORICAL

t

PRESS OF THE

jfoott & Dairies Companp

ATLANTA: I9O7

CoPTfBIOHT 1907 BY

H. P. BELL

PREFACE.

The author has lived in eventful times. He pre

sents to the public in this unpretentious volume,

sketches biographic, historic, reminiscent and analec

tic of some of the men aiid things that have made them

eventful. He does so in the ardent hope that they

may be interesting to the present generation, and use

ful to future ones.

Gumming, Ga.,

HIBAM P. BELL.

March 7, 1907.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

CHAPTEB I. Parentage and Birth of the Author.

CHAPTEB II. Boyhood on the Farm.

CHAPTEB III. The Old Field School.

CHAPTEB IV. Education, Admission to the Bar and Marriage.

CHAPTEB V. The Bar of Georgia in 1850.

CHAPTEB VL Changes in the Law and Its Procedure since 1850.

CHAPTEB VJLJL. Secession and Reconstruction.

CHAPTEB Vlll. Conditions after the War Lawyers.

CHAPTEB IX. Amusing Incidents in Court.

Secession.

CHAPTEB X. V.

In the War.

CHAPTEB XI.

CHAPTEB XII. Second Confederate Congress.

CHAPTEB XIII. Personnel of the Members of the Second Congress.

CHAPTEB XIV. Lincoln and Davis.

CHAPTEB XV. Condition of the Southern People at the Close of the

War.

CHAPTEB XVI. The Forty-third Congress and Party Leaders.

CHAPTEB XVII. The Forty-fifth Congress.

CHAPTEB XVI1L Disappointed Ambition.

CHAPTEB XIX. Social Problems.

CHAPTER XX. Woman in War.

CHAPTEB XXI. Reminiscences of Some Famous Preachers.

VI.

CHAPTER XXII. Russo-Japanese War President Roosevelt Peace.

CHAPTER XXIIL Legislatures of 1898-9, and 1900-1 In the House

and in the Senate.

CHAPTER XXIV. Life, Service and Character of James Edward Ogle-

thorpe, the Founder of Georgia.

CHAPTER XXV. The Religion of Christianity.

CHAPTER XXVI. The Miracles Coincident with the Crucifixion.

St. Paul.

CHAPTER XXVII.

CHAPTER XXVIII. Bishop A. G. Haygood.

CHAPTER XXIX. The Causes of Crime and best Methods of Prevention.

CHAPTER XXX. Literary Address delivered at Commencement of Madi

son Female. College.

CHAPTER XXXI. Semi-Centennial Address.

vn.

MEN AND THINGS

CHAPTER L

AND JftKtB OF TEJD

I was bom in Jiekson County, Ga., January 19th, 1S37.

Jtfj father wag of English extraction. He was a native of Guilioid County, North Carolina, He was bom July 23, 1704. H ncme vu Joeepb 3cctt BeU, Hia father, !Prancis Bell, raflored ftom Sbrlh Carolina, tnd settied in Jickaroi Cotrnty, Gi t abont the year 1800. HP died ID 1S37, at iin ag^ hf Dine^one jeara. Se wsa a Eon-eonuoiBaianed officer in tJie Ooatin^ntril urmj? and failed to be in the battig of Quilford Court House, by reason of beiag in. commutd of a flqofld on detacfcfd wjrvifs. My father vms t miin of iron constitution, phjeicfiJlj, of bigb temper, strong j-mpnl^ rcflolnte will and fearless courfigp, Hia edu cation was limited, befog suet only as could be obtained by A abort, irregular attendanee upon irLfermr nduwla in the bact-voods. He was by occopation, a fanner; never Aeld a ciyil office, and waa neer a eandidete fnr one. In politica IB was a ^States Righls He was no trader. E3s ccnunuiuciti&nB ffere

und "HILJ, nay.l> He waft thu puniuH uf

2

MEN A.ND TSIVOS

labor. I do not remember to have known him to spend an hour in idleness.

My mother was Rachel Phinazee, a native Georgian, and of Irish descent. Like my father, she was brought up in a newly settled country, from which the Indians had but recently disappeared, and therefore, her edu cation was meagre. With poor people, in a newly settled country, bread-winning was the watchword. She was born on the second day of November, 1794. Her mother, whose maiden name was Sarah Harris, died at the advanced age of ninety-one years, which age, my mother also attained. She was distinguished for plain, practical common sense, unremitting industry, devotion to duty and faith in God. Her spirit was quiet and gentle as a May zephyr, and even her reproof was in tones sweet as the "Spicy breezes of Araby the blest." Success did not elate, nor defeat depress her, but always and everywhere she maintained that self-poise which is the offspring of philosophy and Christianity.

My father and mother married young, probably in 1813 or 1814; and located in a cabin in the woods, on a small tract of land given to my father by his father. This was in the northeast portion of Jackson County, Ga., fifteen miles from any town. Here they lived and toiled in agricultural avocation, until 1838, when, immediately after the removal of the Oherokees to the West, my father bought a few hundred acres of land in the woods, unmarked by human invasion, except an In dian trail, leading from the Chattahoochee to the Etowah River, in the county of Forsyth, to which a part of his family removed in the early part of the year

MEN AND THINO8

S

1838. The remainder of the family joined this col ony in the spring of 1840. Here he repeated the ex perience of his early life, the building of a home, and clearing a plantation in the woods, unscarred by the civilizing touch of the axe and ploughshare. Here he wrought, until he "crossed over the river, to rest under the shade of the trees."

The family of my father and mother consisted of six sons and six daughters, all of whom lived to attain majority, and a majority of whom passed the allotted threescore and ten years. The senior son, Joseph T., died at the age of twenty-two years. His death left a scar in my mothers heart that never healed.

My parents were both deeply religious. They united with the Methodist Church shortly after their marriage. My earliest remembrance is associated with the visits of ministers of the Gospel at our home, which was always open to them; and with the regular and syste matic family worship. Such was their admiration for them, that they gave to each of their six sons, the name of a favorite preacher.

My father was an official of the church either stew ard, class-leader, or trustee practically all hia church life. He was a man of extraordinary power in prayer. I have heard him often, at the family altar, pray with an earnestness and power and pathos, that seemed to me to make the foundation of the house tremble. Faithful, earnest, consistent, devoted Chris tians, they lived together in harmony, peace and love, for more than sixty years, until all of their children

4

ME* AND THINGS

became grown, and married; and passed away without a cloud upon their spiritual horizon.

On a calm, moonlight night in May, 1876, I wit nessed my fathers translation; with a face all radiant with the light of high communion, his last utterance was: "I leave the world in triumph," and gently ex changed the cross for the crown. My mother survived him nine years. In September, 1885, at the home of her daughter, in Cumming, Ga., she closed a long life, with the stainless record of duty faithfully done, suf ferings patiently borne, wrongs freely forgiven, and faith unfalteringly kept; and passed sweetly into the joys of the true life. I honor my parents for their character and their virtues; I bless their memory for their love and benefactions to me, in a thousand dif ferent forms.

CHAPTER H.

BOYHOOD oir THE FABM.

Those familiar With the history of Georgia during the first half of the nineteenth century, will remember that, at the close of the Revolutionary War, but a small part of the State, extending from the coast up the Savannah River, was occupied by white inhabitants; the bulk of the territory, of what now constitutes the "Empire State of the South," was wild woods, occupied by hostile Indians and wild beasts^ The absence of money and commerce, the continental war-debt, appre hension of failure in organizing successfully the new system of civil government, and the general demorali zation resulting from the war, and the disorganized state of society generally, created the conditions to be met. These conditions developed the cardinal factors in achieving our present advanced type of civilization enterprise and industry. Men and women went bravely to work to win bread and better their condi tion. Controversies were adjusted, and treaties nego tiated with the Indians, population poured in, new counties were formed, forests subdued, the wilderness reclaimed, churches and school-houses built cheap and humble at first, it is true, but they were the seed of a harvest to be gathered later.

That portion of Georgia lying west of the Chatta-

8,"

6

MEN AND THINGS

hoochee Eiver, known as Cherokee, Georgia, waa the last portion of the State opened for settlement by the white people. It was occupied by an industrious, hardy class of people, with small means, very speedily. There were few slave-holders among them. The set tlement of this section of the State took place at tne time when President Jacksons removal of the deposits from the national bank, and specie circular burst the bubble of "flush times" sent the wild-cat banks, which had sprung up like Jonahs gourd, to grief; and left the- people in debt without a circulating medium. Tinder these conditions from 1840 to 1847 and be tween thirteen and twenty years of age, from sunrise until sunset, in winter and summer, I was engaged, without intermission, in work on the farm, which con sisted in the winter season, in clearing and fencing the land, cutting, hauling logs, and erecting buildings. The county was heavily timbered, which was wasted with reckless prodigality. Each neighborhood had its circle of fifteen or twenty neighbors; and every spring, as regular as the Ides of March, each neighbor had his regulation log-rolling; and in the fall, each within "the circle had his corn-shucking. The house-raising waa another institution of these primitive times. This waa carried on either in the winter or in the summer, be tween the crop-finishing and fodder-gathering season.

These good people wrought hard and constantly, without money; and strikingly illustrated the truth that: "Man wants but little here below." They were plain and simple in their dress; the cotton patch, flocks, cards, spinning-wheel, loom-room, and deft hands of

MEN AND TB12T08

7

good, virtuous house-wives, supplied the wardrobe. Jt was not long, however, until the farm, herd, orchard, garden and dairy, poured their treasures into the refec tory in a variety and profusion that would satiate the appetite of Milo, or eclipse the board of Lticullus. They lived like princes on the proceeds of honest labor.

In those days many communities had its little log church, built after a vigorous controversy over the place of its location, at which they held their Sundayschool and attended preaching, which was often on a week day, and to which the men would go from the field and the women from the loom all in fatigue dress. They went to hear the Word of Life, and were generally thrilled by its power, and comforted by its solace. They lived in peace, all, or most of them, unconscious of what was transpiring in the great big world around them. If they were denied the blessing of different en vironments and a more advanced state of civilization, the law of compensation exempted them from the an noyance of an army of cooking-stove, sewing-machine, and insurance agents, and peddlers of rat poison and Chinese grips. It was not long, however, until the thin-nosed, irrepressible wooden-nutmeg Yankee clockpeddler put in his appearance.

It is written: "In the sweat of thy face shall thou eat bread." My boyhood life on the farm is a striking illustration of the truth of this divine statement. An accident to an elder brother in the spring of 1834, sent me to the plow at the age of seven years. Other hands put on the gear and tied the hamestring, and a friendly stump or fence corner, after climbing, enabled me to

8

IfBN AND THINGS

reach the back of the horse. In 1843, in the absence of my father, I bossed the farm. The weather was phenomenally cold in the winter and spring, forage was scarce, live-stock died a magnificent comet stretched across the southwestern heavens. Millers prediction of the approaching end of the world alarmed the superstitious. It snowed in March, and the ground was deeply frozen as late as the 5th of April; and vegetation indicated no sign of appearance at that date. A little later, an indiscreet neighbor put out fire on an adjoining farm in dry, windy weather, which caught the dead timber on my fatters farm, set the fence on fire, and necessitated the tearing down and rebuild ing of between two and three hundred panels, to save the rails. I felt something of the consternation of Napoleon, when he discovered the blaze of Moscow. I did not retreat, but saved the fence. How much trouble, labor, expense and solicitude we could save others by a little caution at the proper time! In the winter of 1842-43 my elder brother and myself made the rails and enclosed a forty-acre lot of land, thirty acres of which was mainly a chinquapin thicket. When the crop of 1843 was finished, my father returned home from a mining enterprise in which he and my elder brother had been engaged, and constructed a threshingmachine, the band of which my two brothers and my self turned, in the month of August, until we threshed out the wheat crop of one hundred bushels, at the rate of five or six bushels per day. In the winter of 1843-44, my elder brother having attained his major ity, left home and entered school. My two youngar

IfSN AND TSINOS

9

brothers and I devoted our time to the clearing of the thirty acres of chinquapin thicket, which consisted in cutting off the bushes near the ground with club or pole-axes.

Early in the month of May, 1844, the brush was burned, the ground was laid off, without breaking, and planted in corn. After wheat harvest, on the twentieth of June, my brother Matthew and I com menced to plow it for the first time. Father and a negro woman followed with the hoes. The rows were nearly a quarter of a mile in length. The watersprouts were as thick, and very nearly as tall, as or dinary wheat at maturity so thick and tall that we frequently lost the row in running the furrow next to the corn. The corn having grown in the shade, was about eighteen inches high, and the stalk but little larger than a well-developed sedge-broom straw; so slender in deed, that when the sprouts were taken from around it much of it fell down. We had been plowing, or trying to plow, for about three hours in this wilderness on an immensely hot day, when I discovered an im mensely large rattlesnake making an effort to dis engage itself from entanglement with the foot of my plow. I shall not attempt to describe my horror, for the reason that there are some things beyond the at tainment of human power. I killed the snake, re ported at once the adventure to my father, and beggedhim to abandon the field, urging that it was tempting providence to take the risk of the snakes. But my father had more faith than I, and scarcely gave my importunate plea a respectful hearing. We ploughed

10

MEN AND TBING8

on for nearly a week; and passing each other near the centre of the field, we stopped and engaged in conver sation. I noticed in a moment my brothers face turned white as cotton. He had discovered a large rattlesnake lying under a bush in the row between us. We loosed our horses, despatched the rattler, and turned to hitch them, when I discovered, under another bush nearby, a companion snake of equal size, which was also promptly despatched. After ten days of ploughing in new ground covered with a wilderness of bushes, permeated with roots and stumps, and in habited by rattlesnakes suffering all the agonies of mental crucifixion we finished the job, with Nil as the result, so far as the crop yield was concerned. A few years ago, as I closed my brothers eyes in death within an hour after I reached his bedside in Milledgeville these struggles, toils and associations of our boy hood came trooping down the dusty aisles of memory, with a power and pathos for which language has no expression.

The year 1845 was eventful in most of the Gulf States, on account of the absence of rain, and the fail ure of crops. Hundreds of families, especially from South Carolina and Georgia, sought homes in the West. Four weeks of the summer of this year is epochal in my history. I had, for that period, the benefit of my brothers instruction. The preceding year, he had. the instruction of a first-class teacher, and was himself an accomplished grammarian. This months instruc tion from a competent teacher laid the foundation for what little I may have attained in the way of education.

MEN AND THINGS

11

In 1846 my father took a new departure in his farm ing enterprise. He had tried cotton, which his boys had shivered with cold in picking during Christmas week and in January and which he had hauled with an ox-team to Madison, Ga., then the head of the Ga. K. R., and sold at two and one-half cents per pound. This departure consisted in substituting a tobacco for a cotton crop. He planted ten acres in tobacco plants. The land happened to be in the most favorable condi tion to produce its largest yield of crab-grass. The season was unusually wet, the growth of the tobacco was retarded, that of the grass, not. After much toil, the crab-grass, late in the summer, was subdued. If there is any one thing for which a farmer-boy ardently pants, it is a few weeks of rest, after the crop is "laidby," and the peach and watermelon season puts in an appearance. But just as this halycon heaven of boyish delight was reached, the tobacco plants must be topped, and the worms and suckers removed. This process consists in pinching off the top bud, and suckers with the fingers; and knocking off the great, green, loathsome worms with a stick, and mashing them with the foot. The operator is bent forward in the broiling sunshine, besmeared with the gum and stench of this plant, and disgusted with the sight of the worms. This is anything but a delightful exercise. It was com pleted, in this case, some days after the drying fodder had suffered for gathering. Then the tobacco-house was to be built and daubed, the plant to be cut, placed on sticks and cured, stripped from the stalk and bound into hands. What the crop yielded in money I do

12

MSN A-ND

not now remember. I am sure it was the only ex periment my father ever made with tobacco. He went back to cotton.

Having attended school all told, only six or eight months in snatches of two or three weeks at a time in the old field school, most of that time to very inferior teachers, even for this grade of school; and having at tained the age of twenty years, without education, I proposed to my father to serve him another year if he would send me to school for one year; or, that if he would release me from the service, I would discharge him from the obligation to give me a years schooling, as he had done for my older brother, and take the chances of educating myself. He generously accepted the latter proposition. It is due to the memory of my dear father to say that he had a high appreciation of his obligation to educate his children, and ardently desired to discharge that obligation. But having a large family to support, always necessarily in debt, settling in the woods remote from schools fitted to be entrusted with ones education, it was utterly impracti cable for him, with these environments, to carry out his wishes in this respect. It is a matter of solace to me, that most of his children, somehow, secured a good English education.

Before I close this chapter, allow me to say that there is one phase of the life of the average cotmtrybrought-up boy, that it would do him great injustice to omit. It is about the time, in his history, when the first application of a dull razor is made to his upper lip, designed to elicit the appearance of an infantile

MEN AND THINGS

IS

mustache, and he is, or thinks he is, desperately in love with a neighbors pretty daughter. My observation convinces me that this event in a boys life constitutes a rule of general, if not universal application, I was not an exception to the rule. On a bright Sunday morning, having blacked my shoes that is, the top of the front portion of them with a mixture of cold water and chimney soot as much as I could induce them to mix donned my best suit, saddled and mounted a small mule, something but little larger, than a full grown Texas jack-rabbit (it was a very small mule), and set out on the Don Quixotic adven ture of calling to see the object of my supposed idolatry. Within a quarter of a mile from the house the road crossed a creek with rather precipitous banks. The mule, as it soon afterwards became apparent, was thirsty. As soon as it came within reach of the water, it very naturally but very suddenly and decidedly un ceremoniously, put its mouth to the water, which left its body in an angle of something over forty-five de grees. The result was, the rider was tumbled over the mules head into the creek, followed by the saddle, which fell on Tiim. This mishap was then esteemed a calamity. It is now regarded as the poetry of the ludicrous. It would present a picture that would shame the genius of Nast, whose artistic skill as a cartoonist broke the heart and caused the death of Horace Greely.

CHAPTER III.

THE OLD FIELD SCHOOL.

The old field school, like some other institutions of this country, has, in its peculiar way, served its day and generation, and by common consent has been rele gated to memory and history. In these days of pub lic school fads, higher educational pretentious, college and university base and foot-ball games, and punch bowl banquets, reference is seldom made to an institu tion which, though lowly in origin and humble in claim, has made possible all these institutions as well as our advanced state of civilization. When it is referred to it is usually with the sneer of derision or the smile of amusement. It seems that such a spirit of ingratitude is capable of repudiating the love of a mother, or re proaching the misfortune of poverty. It met a condi tion of society at a time and under circumstances which could not have been met without it. It kindled a light that makes the opening years of the twentieth century all radiant with the glow of intelligence. The "old field school" possessed three distinctive sides the ludicrous, the sentimental and the useful. Its houses, furniture and comforts, as well as the extent of its curriculum and the qualifications of its teachers, com pared with those of the present time, appear ludicrous in the extreme.

14

MEN AND TBINOB

15

The school-house was usually located in the corner of an old field cleared by the Indians, or in the woods, constructed of small round oak or large, split pine logs, notched down at- the corners and covered with clap boards. The orthodox dimensions were 24x16 feet. The larger part of one end was devoted to what is known as a "stick and dirt chimney." Economy in labor and money was promoted by dispensing with sleepers and floor, and substituting the ground therefor. The furniture consisted of a small, rough pine table and a superannuated chair in the rear of it. This was the throne of the intellectual sovereign. The seats for the pupils were made of oak or chestnut logs about six inches in diameter, split open in the center and pegs driven into auger holes from the round side of the halflog. These pegs were of a length that would prevent the feet of the urchins occupying the benches from reaching the dirt floor by a distance of from six to eight inches. To occupy such a seat for a long, hot summer day was a penance that ought to atone for a multitude of sins. The remaining article of furniture was the writing bench. This consisted of a rough plank nailed to. the top of a frame, as nearly on a level as practicable, twelve inches wide and ten feet long, and a plank of similar dimensions joined to each of its edges, slightly inclining downwards.

The aesthetic will perceive that this equipment, in the line of convenience and comfort, was neither ex pensive nor elaborate. The curriculum was not exten sive but it had the merit of being in harmony with it3 surroundings, and confined, within the constitutional

16

ME2f AND THIN0B

limitation, to "the elements of an English education

only." It embraced spelling, reading, writing and

arithmetic The standard text-hooks were: The Ameri

can Spelling-book, the American Preceptor and Dilr

worths or Fowlers Arithmetic. A little later, as this

class of educational institution advanced, the Colum

bian Orator and Weems Life of Washington were

added.

The teachers, in the main, were men of advanced

age, too lazy to work and too poor to live without it.

Having appeared after the age of [Raphael, Titian,

Angelo and Keynolds, and passed away before the dis

covery of Daguerre, the world has lost the pleasure

of looking upon their pictures and must rely only upon

such faint and imperfect pen-pictures as memory alone

can supply.

I have in mind with some degree of distinctness, the

image of four of them who are strikingly typical of the

class. For fear of marring the pleasure of some filial

descendants in tracing his heraldry, for the discovery of

his ancestral escutcheon, I refrain from stating names.

Indeed, the given or Christian name of the first one to

whom I refer is forgotten. I only remember that his

students, by common consent, substituted for it, what

ever it was, the name "Nipper," so that he was known

only as Nipper A s. I do know, however, that

he was a tall, ungainly, bald-headed, sour-tempered old

man, with no magnetism and but little intelligence. He

was not deficient in physical force, as two certain boys

.1

who engaged in an innocent game of "hard-knuckles"

during study hours when he was supposed to be asleep,

MBIT AND THIN&a

17

after having visited, at the noon recess, a neighboring still-house, discovered to their mortification and discom fort.

The next one, W , whose only possession was a homely wife and a bad "small boy," was an Irishman of exuberant cheerfulness. No conditions seemed to discourage or dishearten him. He secured his sup port, principally, from his neighbors by borrowing such articles of food as were necessary to prevent actual starvation, under the pretext that "to his surprise, he had ascertained that the articles desired had just been exhausted at home," and with the munificence of a prince bestowing an "order" or conferring a proconsulship upon a grateful subject, he promised to return it with manner that simply defies description, except to say that it was done in a way of Irish shrewdness that made the lender feel that he was the beneficiary. This feeling was the only benefit he ever received for the loan. His theory of teaching seemed to consist, judg ing from his practice, in the belief that light could be communicated to the mind by the application of force to the body.

H , unlike W , was a man of some means. He had a wife, a very large family of children, five or six dogs and two rifiegnns; the stocks of which were well worn by long use. Mr. K was a man of large frame, dark complexion, of slow motion and deliberate speech; though of robust health he seemed to be averse to motion, and the act of breathing appeared to be irk some to him. If the "law of the Lord" was not his delight the law of inertia was. His uncharitable

18

MBN AND THINGS

neighbors entertained the suspicion that he was afflicted

with an attack of remediless laziness. Of the truth

of this imputation, posterity must judge. I only state -

the facts in the case.

F , the remaining member of this quartet of

famous pedagogues, was a man of decidedly marked, if

not unique, personality. His stature was low, his head

large and of peculiar form, his lower limbs short and

bent with a regularity that fitly represented the seg

ment of a circle, the convex side being outward; his

feet inclined to the club variety; his walk was sort of

hobbling and shuffling movement. The conception of

a cross between a chimpanzee and a dwarf would pre

sent the nearest an ideal picture, of which his figure

was susceptible. In bestowing her gifts, Nature had

been parsimonious with him; some and among them,

beauty had been entirely withheld. An officiating

clergyman said at a vagrants funeral, that ^Whatever

else might be said of the deceased, all would admit that

he was a good whistler." So I can say of this dead

pedagogue (and it is about all that could be said), he

wrote a beautiful hand.

These great men of the olden time were differen

tiated, mainly, if not solely, in their personality. They

were all old men. They were about on an equality in

scholarly attainments, perhaps I should say, in the

.j

absence of scholastic attainments. They all taught at

?| ,

the same place, used the same books, practiced like

>

methods and quenched their thirst at the common "still-

house."

As the branches taught were few, the methods em-

HEN AND TBINO8

19

ployed were simple. The lessons were studied vocally, not silently, and by far the largest portion of the study consisted in the hubbub of mingled voices in every va riety of key. The full measure of vocal power was developed in preparing the "heart lesson" preceding the evening adjournment. With favorable atmospheric conditions the hum of this noise could be distinctly heard at the distance of a mile, and the peculiar shrieks of one boys voice (Duncan Campbells) could be easily distinguished at that distance. The useful art of writing was taught by commencing with a socalled "line of straight marks" across the top of a leaf of coarse, unruled paper. This, of course, was made by the teacher and called the "copy." The beginner, equipped with a goose-quill pen and the juices pressed from oak-balls (well known among the scholars as inkballs) for ink, commenced the process of copying the marks. The second lesson was the mark, as in the first, curved at the bottom and traced upward. This mark, in the figurative language of the teacher, was called "pot hooks." The third copy was a line of "pot hooks" with the second line curved at the top and brought down to evenness with the lower curve; then followed copies of capital letters of the alphabet, etc. It was a singular fact that the students almost inva riably in making these curves, slightly twisted and pro truded the tongne, and kept the tongne and eyes in a movement precisely corresponding to the motion of the pen. I never did understand, and do not now know, which was the dominant motor in this operation these members or the pen. I had the privilege of securing

20

MEN AND THINGS

early instruction from each of the worthies here men tioned, in an institution which I have endeavored to describe. Whatever mistakes in instructions or dis cipline they made I forget and forgive. For whatever of good they did me, I give them the thanks of a heart, which I trust is incapable of ingratitude.

THE SENTIMENTAL SIDE OF THE OLD FIELD SCHOOL.

"A land without sentiment is a land without liberty." The short resolution adopted by the Pilgrim fathers in the cabin of the "Mayflower" was the prophecy of our magnificent structure of democratic constitutional gov ernment. They symbolized the religious faith of the United States as they stood on "Plymouth Kock."

"And shook the depths of the forest gloom with hymns of lofty cheer."

The old field school was our present civilization in embryo. It was the beginning of what now is. Pioneer settlers were always distinguished for their energy, industry, fearlessness and faith. This school was theirs. Indeed, it was the pioneer educational institu tion of the North American wilderness.

On a Monday morning, late in July or early in August, coming from all directions, in a circle within three miles around the school-house, from forty to fifty children of both sexes, ranging in age from five to twenty years, might be seen to meet at the school-house. They were simply and cheaply clad in such apparel as their good mothers could manufacture. They were all barefoot, except the few grown girls. They were all

MSN AND THINOB

21

bronzed by the mingled force of hard labor and hot sunshine. The commissariat consisted of bacon, or steak, sandwiched between slices of corn-bread, or bis cuit, neatly wrapped in a clean napkin and placed in a small tin bucket, or basket, and a black quart bottle which had seen other service filled with butter-milk and closed with a corn-cob stopper. The dessert peaches and apples were carried in the boys pockets. There was no difficulty in arranging classes. All that was necessary was to point out and assign as lessons, the alphabet, the lesson in spelling and the multiplica tion table. A few lessons being recited, the noon re cess reached and lunch over, they assembled on the play ground, and speedily renewed old and formed new acquaintances. They cared little for the ceremonious etiquette of courts, or the military discipline of camps. These children on the play-ground presented a scene on which idle angels would delight to look for.

"They also serve, who only stand and wait." The games they played, if lowly and rustic, were healthful and harmless. Their section of the country, at least, had not been favored with the entertainment of the cock-pit, the bull-fight, nor foot-balL Nor had a powerful daily press then delighted the public with columns of detailed description of the bloody "rounds" of Jeffries and Fitzsimmons. To preserve the facts of history, a list of them is given; they were: Base, tag, cat, marbles, bull-pen, town-ball, shinny, roly-hole and mumble-peg. Both sexes joined in the first two named, therefore base and tag had precedence in popu larity. I always thought, for the reason, that the exe-

22

HEN AND TSIN08

coition involved the thrill of touch. These children had a common experience in labor and poverty; had learned self-denial and self-sacrifice; had waded in the branch and been charmed by the ripple of its tiny water falls; had gathered autumnal fruitage in the tangled wildwood; had breathed alike the fragrance of the rose and honeysuckle; had listened in ecstacy to the chorus of the birds and gazed in wonder upon the stars that deck the diadem of night. They had communed with Nature and reveled in its charms until their life had become an unwritten idyl. They had likewise realized in their short, young lives all the emotions of hope and fear, of success and defeat, trial and triumph, and grati fication and disappointment.

As they stood on the play-ground about to advance a step in the social and intellectual world, each felt the consciousness of a force within that was not understood, and that could neither be denned nor described, still it throbbed in the brain, pulsated in heart-beats and gurgled through the veins. It was present in their ambitions, aspirations, admirations, envyings, rivalries, likes and dislikes. What was this force? Was it the struggling of the mind for higher attainments in knowl edge, the panting of the restless spirit for the solace of peace, or the thirst of the soul, clamoring for one full draught of immortality? No body can tell. No one knows. Whatever it was, it was the power, dying

"Ion caught from Clemanthes eye"

that assured him of a reunion of love,

"Beyond the sunsets radiant glow."

MEN AND TBZN&8

23

If they never heard the name of the poet, nor read the couplet, they all felt the sentiment that

"Kind words were more than coronets, And simple faith, than Norman blood." It was very soon discovered that in playing the game of base some boys were very easily caught by certain, particular girls. It was further observed that the same boys and girls, in going home in the evening, would linger at the parting of their ways and play, or pretend -to play, "tag." They parted with the com pact, that whichever one reached the place first on the succeeding morning, in returning to school, would make a cross-mark or drop the twig of a green bush in a particular place in the road. This sign always accel erated the movements of the party of the second part. I never heard of any complaint of violating the stipu lations of this treaty. It may be, after all, that these trivial, simple little things shed light on the solution of this great problem that has baffled the learning and exploded the theories of psychologists. It was a little thing to dip seven times in "Jordan" but it healed a leper. In long after-years and from far-away places, many a heart has sent memory back to the old play-ground, and silently sighed for

"The touch of a vanished hand," and the sparkle of an eye forever closed.

THE USEFUI. SIDE OF THE OLD FIELD SCHOOL.

It must be remembered that the school under con sideration, was the educational initiative, the first

24

MEN AND THINGS

grade or primary species of the genus old field school. This grade did not, and necessarily, could not exist long. It was subject to the great law of gradation, progress and development, which seems to have dom inated the process of creation, as well as the disclosures of revelation. As the good people improved their con ditions, increased their means and enlarged their views, they built better houses, used superior books and em ployed more capable teachers. Occasionally, in a more wealthy neighborhood, an academy would spring up, and as new counties were formed the law provided for the establishment of an academy at the county-seat. In the meantime the University was struggling up to the guerdon of triumph; later the great churches built colleges for both sexes; finally public sentiment crystalized into constitutional provision for the public school system.

The first grade of the old field school, as described in these pages, is the granite bed-rock upon which this superb superstructure rests. It was the small seed from which this luxuriant harvest within the period of a century was gathered. The children of this school, belonging to the same grade of society, identified in common environments, and the sympathies which result from early association (at least many of them), mar ried and organized homes in the quiet country, in which peace, gentleness, affection and contentment ex emplified the only remnant of Eden, unblasted by the falL They became the parents, and grandparents, of a race of men and women that subdued the wilderness, beautified it with gardens, orchards, farms, towns and

MEN AND THINGS

25

cities, and crowned it with temples of worship and learning, and hospitals and asylums. A race of chiv alrous patriots, who in 1812, dispersed the boasted navy of England, sent back to her, from New Orleans, the pickled corpse of Packenham; scaled the rocky heights of Cherubusco, Chepultepec, Milino del Key; floated the American flag from the dome of the eapitol of the Aztecs, and spangled the "milky way" of national glory with a gorgeous jewelry of stars.

The people provided the old field school for them selves. It was the best they could do, and they deserve the grateful thanks of all the coming ages for what they did.

There were two other potent factors co-operating with the old field school in laying the foundation for these achievements. They were the Decalogue and the Sermon on the Mount Side by side with the school appeared the irrepressible Methodist circuit rider, with his much-used and well-worn Bible, hymn-book and "Discipline," preaching every day in the week, at the little log church or school-house, and at night fre quently at some house of a brother in the neighborhood. At the same time the Baptists appeared, preaching on Saturday and Sunday. The preaching of that day dealt with the doctrines of depravity, repentance, faith, regeneration and obedience, as taught in the Bible, with occasional reference, by the Baptist brethren, to some of the dogmas of the ironclad theology of Geneva, such as election and reprobation, final perseverance, mode of baptism, etc. These combined forces formed the char acter of a good people and directed the course and

26

MEN AND THINGS

shaped the destiny of a great nation. The power of many of these men finds fit expression in Wirfs de scription of the blind preacher: "They spoke as if their lips had been touched with a live coal from off the Altar." They accepted the Mosaic cosmogony. They taught that "the Son of Man came to seek and to save that which was lost," and that He brought "life and im mortality to light." They indulged in no speculations on the "glacial" and tertiary periods, nor did they waste any time in searching for "protoplasm," nor tracing their paternity, through the processes of "evolution," to a monkey progenitor.

Schools, academies, colleges and universities can not educate. They can only supply the means to aid and enable people to educate themselves. Education, in its last analysis, is a personal work, facilitated by the aid of helpful agencies, or retarded, of course, by their absence. To become thoroughly educated, compara tively, requires a life-long, unremitting, systematic pro cess of observation, reading and thinking; and this can only be done by the student himself. The great and learned Newton said that he "had only picked up a few shells on the shore, while the great ocean of knowl edge lay, unsailed, beyond him." The old field school did its work, and did it welL Like the "Mother of the Gracchi," she can present George Washington, Ben jamin Franklin, Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay and Abraham Lincoln, as her jewels, and proudly challenge Harvard or Tale, Oxford or Cambridge, Leipsic or Heidleberg, or all of them combined, to duplicate this quintet of American immortals.

CHAPTER IV.

EDUCATION, ADMISSION TO THB BAB, AND MABBIAGB.

At the age of twenty years, with an attendance, al together, at school, of six months four at the old field of the first grade, and two of the second grade. I left home "with the blessing of my parents, and entered on the battle of life. My wardrobe was such as my dear, good mother could provide. I had a purpose (this was all), owned no properly, did not have one cent of money; bought books and secured board and tuition, on credit; and entered the academy at Gumming, in Feb ruary, 1847. It should be stated that my school in* struction had been supplemented by studying during the long winter nights, with my brothers and sisters. We had many and most interesting "spelling-bees," and recitals, in English grammar and geography. I made it a point to read every book upon which I could put my hands; and in 1845, I had the advantage of very superior instruction from my brother, for five weeks, who taught near Sheltonville, Ga., the odor of whose lessons has lingered for threescore years, in the com munity, like the fragrance of roses that have once been distilled.". The principal of the Academy, Joseph K. Valentine, was a professional teacher, in middle life; a fine scholar and a gentleman. He was so thor ough in the Greek and Latin languages, that he read

27

i

28

MEN AND THINGS

the text-books in the course as promptly and with as

much facility, as he read English. The students, in

constant attendance, numbered about one hundred, half

of whom, approximately, were grown. It was a mixed

school. In arranging the classes, it was my good for

tune to be assigned to a class of five grown girls, in-three

or four studies. In preparing the lessons in these

studies, we occupied seats together. Being further ad

vanced, especially in English grammar, than any of

them, I was helpful to them in that study. I had

parsed most of Miltons "Paradise Lost," and when sur

rounded by this coterie of beautiful girls, I felt as if I

was in "paradise found." One of the most interesting

and valuable lessons, was ttie "Heart" spelling lesson.

The class was a large one, more than twenty, of the

grown students. The book used was "Towns Speller

and definer," a book of something over 300 pages, con

taining the words in most common use, with accurate

definitions. The first thing after the noon recess was

this lesson, which had been carefully studied during

the recess. The class stood in a line; the teacher called

the word, and the class spelled and defined it. At the

formation of the class, each student took his place at

the nearest point at which he reached it; before the

end of the second lesson the five girls and myself were

the first six in the class, counting from the head four

of them above and one below me. We stayed there

for one year not one of the six missed the spelling or

defining of a word in the book for that period. These

girls were: Virginia M. Lester, Martha Erwin, Joseph-

N

ine Strickland, Virginia Sims, and Mary Sims. They

MEN AND THINGS

29

all had been trained by practical, sensible, good parents; were all of nearly the same age and size, were social chums, ardent personal friends, free from malignity and envy, bright as stars, and animated with ambition and rivalry to excel each other. A years class and social association with them failed to discover the slight est defect or weakness in the character of any one of them. The respect, confidence and friendship of all of them, and the priceless love of one of them, have been the blessing and solace of my life. And now, the precious memory of them comes to my spirit, sweet and sad, as the tremulous echoes of a nightingales dying song.

Within three months from the day I entered that class, Virginia M. Lester and myself were engaged to be married so soon as I finished my education, and was admitted to the bar. As unwise and reckless as this engagement may have then seemed, time and trial vin dicated its wisdom. Her bright smile, like light on "Memnons lyre," set my heart to throbbing with the music of love, that was as resistless as a decree of des tiny. She was in the bloom of young womanhood. The ease and grace of her pose, the simple elegance of her manner and the beauty of her face and figure, would have delighted an artist, as a model for his masterpiece. Added to these charms was a spirit radiant with the light of hope and joy; and a heart, pure as love, and faithful as truth. For thirty-seven years she made more than one heart contented and happy, and one home a paradise of peace and love. She merited the highest eulogium ever pronounced on woman that which came

30

MBN AND THINGS

from the lips of the Nazarene, when he said of Mary of Bethany: "She hath done what she could." I loved her, living, with an ardor for which language has no expression; I mourned her, dead, with an anguish for which earth has no consolation.

Josephine Strickland married John B. Peck, of At lanta, Ga., and was the first of the class to pass away. Mary Sims married Lewis D. Palmer, now of Nash ville, Tenn. She and Virginia M. Lester died on the same day, April 30, 1888. Virginia Sims married Mr. Backman both are dead. Martha Erwin, who mar ried Mr. W. H. Camp, now of Floyd County, Ga., ia the only survivor of this class of splendid girls and noble women. She is now in "the sere and yellow leaf," but possesses all the sweetness, gentleness, mod esty and sly humor of the long ago.

My studies were grammar, geography, philosophy, chemistry, logic, rhetoric, composition, history and the Latin language. In spare hours I read "Plutarchs Lives," Irvings "Life of Columbus," Prescotts Con quest of Mexico," Senecas "Philosophy," and Locke on "The Understanding." I pursued these studies in this school during the year 1847 and the greater portion of 1848. In 1849 I taught in the Academy at Ellijay, Ga.; and read law. I was admitted to the bar, at Spring Place, Ga., on November 28, 1849, by Judge Augustus R. Wright, after an examination in open court of four hours, by a committee consisting of Judge W. H. "Underwood, Judge Turner H. Trippe, Warren ATnTi, J. W. Johnson, William Martin, and B. W. Jones. I entered upon the ordeal of that examination

ItXN AND THINGS

SI

with a trepidation that makes me shiver to think of now, but my good angel was not nodding at his post; and it so happened that I did not fail to answer every ques tion correctly. In pursuance of our engagement, Vir ginia M. Lester and myself were united in. marriage in Gumming, Ga., on January 22, 1850. I taught that year, in Ellijay; and continued my study of law. In, the latter part of that year, we settled in Cumming. I possessed only two things the best of wives, and the noblest of professions.

On June 11, 1890,1 was united in marriage to Miss Annie Adelaide Jordan, in Eatonton, Ga., at the home of her aunt, Mrs. M. L. Keid. She was the daughter of Warren H. Jordan, of Nbxubee County, Miss. a native Georgian and her mother was Miss Julia L. Hudson, of Eatonton, Ga. both of whom died before she was grown. She is an accurate scholar, and an ac complished pianist. Her sweet and gentle ministries of love and devotion to me, in joy and sorrow, in health and in sickness, have imposed upon me an obligation, of gratitude I can never recompense.

CHAPTER V.

THE BAB OF GEOBGIA IN 1850.

At the time I was admitted, the bar of Georgia, com pared most favorably with that of any State in the "Onion indeed, with that of any age or country. At its head were John M. Berrien, Kobert M. Charlton, William Law, Francis S. Bartow, John E. Ward, Charles J. Jenkins, George W. Crawford, Andrew J. Miller, Robert Toombs, Alexander H. Stephens, Wil liam C. Dawson, Francis H. Cone, Joshua Hill, Augus tus Reese, Linton Stephens, Augustus H. Kennan, William McKinley, Eugenia A. Nisbet, Barnard Hill, Washington Poe, Samuel P. Hall, Absalom H. Chappell, Henry G. Lamar, Seaborn Jones, Walter T. Colquitt, Martin J. Crawford, Hines Holt, Henry L. BenTnng, William Dougherty, Hiram Warner, Robert P. Trippe, Herschel V. Johnson, Edward Z. Hill, Benja min H. Hill, Charles Dougherty, Junius Hillyer, Howell Cobb, Hope Hull, Thos. R. R. Cobb, James Jackson, Cincinattus Peeples, Thos. W. Thomas, B. H. Overby, Nathan L. Hutchins, Charles J. McDonald, David Irwin, Andrew J. Hansell, George D. Rice, Wil liam H. Underwood, Turner H. Trippe, Warren Akrn3 Augustus R. Wright, George N. Lester, John W. H. Underwood, Edward D. Chisolm, Joseph E. Brown, Logan E. Bleckley, Dawson A. Walker, William H. Dab-

32

URN AND THINO8

S3

ney, John B. Floyd, O. A. Lochrane, James L. Calhoun, James Starke, William Martin, and the first Chief Justice of the State, Joseph Henry Lumpkin. This list of illustrious lawyers furnished cabinet min isters, senators and representatives in the United States Congress, equal to the best in the Union; governors, judges of the supreme and superior courts of the State; and ministers to foreign countries. It contained many of the ablest statesmen and most eloquent orators of the age. In their day, they led the public sentiment, and moulded and shaped the public policy of the State, and largely, of the nation. They were the leaders of the bar. Yet there were hundreds of lawyers, very nearly, if not quite, their equal in legal learning and professional skill, in the management of causes in the courthouse.

The country will never know its wealth of talent and capacity for public service, for two reasons the mod esty of meritorious men, and the lack of opportunity. Public position, like the clowns measles that "struck too large a family to go round," can not furnish the op portunity to all the capable and meritorious.

As a class, lawyers are the closest thinkers, and best logicians in the world. The reasons are obvious. The science of law trains its votaries in the best methods of securing its object, which is the ascertainment of truth and the enforcement of right.

The definitions of the law are clear. Its distinctions being fine, must be accurately observed and drawn, con flicts (or seeming conflicts) reconciled, language con strued, doubts resolved, and its application to faota in-

34

IfBN AND TSINOS

finitely varied made; all to be done with reference to the rights of an anxious client; and involving the reputation of the lawyer, and frequently the bread of his family. His profession is a direct intellectual com bat with an antagonist that may be relied upon to do his best to defeat him. The struggle is in the open before the public with a judge present to decide who is victor or vanquished. The practice of the law is the best possible training in the art of successful disputa tion. It has the incentives to thorough research and thought, to the examination and study of both sides of a case or question. He studies the strength and the weakness of his adversary. He learns much of human nature and human infirmity by contact with parties, witnesses and jurors. It has been urged that the study and practice of law contracts and narrows the mind. Precisely the contrary is true. It expands the horizon of mental vision, enlarges the field of investigation, of inquiry, and liberalizes the process of thought. Law, in its different departments, of in ternational, national, civil, criminal, military and mari time, comprehends every right and interest of man ab solute and relative, in all his relations. Familiarity with it and the knowledge of it, therefore, extend the range of thought, and increase the domain of knowl edge. Jefferson and Hamilton, Pickney and Wirt, Webster and Choate, Clay and Crittenden, Prentiss and Douglass, and Stephens and Toombs, illustrate and dem

onstrate this truth.

Able and upright lawyers are no unimportant factors in conserving the moral interests of society and eleva-

MEN AND THINGS

.

35

ting the tone of public sentiment to proper standards. The vindication of rights, the denunciation of wrongs, the maintenance of truth, and the exposure of false hood, in the discussions of the courthouse, involving, as they do, the interest and rights of every spectator, is an education by no means lost on the public mind. Discussions of moral questions in the pulpit and on the platform deal with them in the abstract, in the court house, in the concrete.

It has been urged that lawyers were ambitious and inclined to seek office and honors. This is not true of them as a class, any more than it is of any class or pro fession. It is perhaps true that more offices in the government are filled by them, than any other class. Civil government is an institution of law; and a knowl edge of the law is an important, if not a necessary, qualification for the duties of the office. In all judi cial offices it is absolutely indispensable, and legal training and knowledge is a qualification for wise and intelligent legislation, as experience has abundantly shown.

Lawyers have always* ^K! the van in the assertion, maintenance and defense of liberty. They have always stood for human rights and against the tyranny of des potism. It was a lawyer who sounded the first note of hostility to British oppression in the Virginia House of Burgesses, in a resolution written on the fly leaf of a law book. That sound had its last echo in the surrender of the Britisb at Yorktown. A lawyer wrote the Declaration of Independence. The Constitution of the United States is mainly the product

I

38

MEN AND THINO8

of two lawyers James Madison and Alexander Hamil

ton. These two great and patriotic lawyers were the

representatives and exponents of two opposite schools

of political thought and theories. They were equally

}

able, honest and patriotic. They each urged their

k

views with the emphasis of conviction. The Constitu-

fi

tion of the United States embodies the compromise of

ij{

these opposing theories of civil government.

k

John Somers, in a five minutes speech, procured the

f;

acquittal of the Bishops, in a trial, that drove the last

h:,

of the Stuarts from his crown and kingdom. The

!"

learning and eloquence of Halifax and Somers obtained

J

in the Convention Parliament, the limitations upon

:

power and prerogative, secured in the Act of Settle-

{:

ment, and the Bill of Rights. The powerful denuncia

tions of oppression by Webster and Clay, in the Ameri-

!

can Congress, thrilled and incited the Greeks to the

!:

resistance of Turkish despotism in Europe, and the

Latins in opposing Spanish tyranny in South America.

In the late war between the States, Bartow fell in

the first fray and Cobb soon thereafter; and hundreds

of lawyers of perhaps less learning and eloquence, but

with equal valor and patriotism, "poured out their

generous blood like water" in defense of the right of

self-government, on more than five hundred fiercely

fought fields.

History amply vindicates the claim of the profession,

to the highest niche in the temple of fame, for devo

tion to learning, liberty and patriotism.

CHAPTER VL

CHANGES IN THE LAW AND ITS PBOOBDUBE SINGE 1850.

At the time of which I write, Joseph Henry Lumpkin, Eugenius A. Msbet and Hiram Warner occupied the Supreme bench. Such men as Edward Y. Hill, David Lrwin, Junius Hillyer, John J. Floyd, Qarnett Andrews, Herschel V. Johnson, Francis H. Cone, Au gustus B. Wright, and many others of equal ability, presided on the circuit bench.

The Supreme Court was established in 1845, after a protracted struggle. The earlier volumes of its re ports contain monumental evidence of the independence and learning of the first three judges. Lumpkin was learned, eloquent, impressive and humorous. Nisbet was equally learned, dignified and elegant; Warner was cold as a Siberian icicle, and clear as a tropical sunbeam. I confess that he was my ideal of a judge. I never think of him, as he sat upon the bench, strug gling, sometimes alone, to uphold the constitution and the law against the debauchery and dishonesty of socalled relief legislation, without applying to him, the magnificent eulogium pronounced by the Attorney-Gen eral, on the dead vice-president, when Gushing said of King: "He stands to the memory, in sharp outline, as it were, against the sky, like some chiseled column of antique art, or consular statue, of the Imperial republic,

37

38

MEN A.ND THINGS

wrapped in his marble robes and grandly beautiful in the simple dignity and unity of a faultless proportion."

The last fifty years have wrought marvelous changes, in Georgia, in the law, its forms of procedure, and the questions with which it deals. The War and the al tered conditions resulting from it have contributed greatly, if not mainly, in producing these changes.

Before, the principles, practice and forms of equity and the common law were separate and distinct; now, they are merged. Then, the English common law forms in all their "vain" repetitions, and technical refinements and distinctions in pleadings, were followed; now, the pleader states his clients case in law or equity, what ever it may be in short, pithy paragraphs. Then, all persons interested in the event of the suit were incom petent witnesses; now, all parties living and sane (with a few exceptions) are competent. Then, only the parties to the record could be .heard in the case; now, anyone, in any way interested, may intervene and be heard.

There has been as decided change in the subjectmatter of litigation as in the forms of proceeding. The institution of slavery was the fountain of a stream that carried fortunes to the profession. The farmers be came rich, breeding negroes, buying land and making cotton. The validity and construction of wills, breaches of warranty of the soundness of slaves, action of trover for their recovery and debt for large amounts of in debtedness upon their sale these and the trial of dis puted land tides, as population increased and settle ments were extended raised the questions upon which

MEN AND TB1NG8

39

the legal giants fought their battles and won their fame and fortunes.

This was the agricultural age of Georgia. The abolition of slavery eliminated, from the courts this source of litigation, and substituted a totally different kind of questions and controversies. The ordinance of the convention of 1865, providing for the adjustment, by the courts of Confederate contracts, upon the princi ples of equity and justice, the depredations and tres passes of home guards and robbers during the last years of the War, and the relief legislation of the reconstruc tion period, filled the courts for a few years with a flood of litigation. But this was necessarily tempo rary, and soon passed away. Now (1904), commercial and corporation law and practice are regnant, and con fined, principally, to the cities and larger railroad towns. In the rural counties the practice arises from the levy of distress warrants and executions upon the foreclosure of liens, and the defense of negroes for larceny, robbery and burglary usually by assignment of the court. How the hundreds of young men, an nually brought to the bar by colleges, universities and otherwise, are to win bread, by the practice, in the light of the present outlook, is their problem; not mine. It is alleged that some of the more enterprising mem bers of the profession especially in cities have hench men employed to hunt up business, and that they follow a train wreck, like vultures, the scent of a carcass. I. hope, for the honor of the profession, that this allega tion is a slander.

This progress, reform, or certainly change in our law,

40

XSN AND THINGS

commenced in 1847 upon the passage of the act which substituted, for the common forms of pleading, the short forms, popularly known as the "Jack Jones forms." The law allowing appeals in the superior court was repealed. The marital rights of the husband as to property owned by the wife at the time of marriage or acquired by her after marriage were wholly changed. The homestead laws enlarged from their pony propor tion up to sixteen hundred dollars worth of property real and personal which, however, is practically nulli fied by the creditor invariably taking a waiver note and mortgage on everything that the debtor owns or ever expects to own. The school law which humanity provided for the education of the poor has given place to a system that imposes annually, upon the people of the State, a tax of nearly two millions a large portion of which is devoted to training negro children in idle ness and crime, under the pretext of qualifying them for useful citizenship. These and numerous other radical changes have been made in our law to such an extent that if a Georgia lawyer had fallen asleep in 1850 and waked up in 1904 Kip VanWinkle would have been no more remembered! Whether these changes were all wise and promotive of the public in terest-raises a question upon which opinions will differ.

The British government sent an agent to this country to investigate the question of law reform, who carried back copies of the "Jack Jones" forms of pleading, which were enacted into law by Parliament. The

MEN AND THINGS

41

youngest of her American colonies, in less than one hundred years from the establishment of its independ ence, furnished to the Mother of the common law her form of pleading.

CHAPTEK VII.

SECESSION AND RECONSTRUCTION.

On the sixteenth day of January, 1861, the people of Georgia, by their chosen delegates, assembled in con vention at the capitol in MilledgeviJle.

This was perhaps a body of the ablest men ever assembled in the State. The magnitude of the issue to be considered and determined induced the people toselect the men supposed to be best qualified to deter mine wisely.

The people were prosperous; many of them rich; all of them peaceful and happy. They owned African-, slaves, numbering hundreds of thousands. Their barns were crowded with fullness and plenty. They ex hibited the finest type of society civilization ever pre sented. This prosperity had been achieved in the Union, under the protection of the Constitution of the United States. The practical nullification of the fugi tive slave provision of the Constitution, by the hostile legislation of fourteen States, and the election of it. President by them from one section of the Union, uponthe issue of hostility to the institution of African slav ery as it existed in the Southern States, convinced a> majority of the convention that their safety and pres ervation of their rights could only be secured by dis solving their relation with States thus faithless to con-

42

MEN AND TBINOB

43

stitutional obligations. Three days after the conven tion met on the nineteenth of January, 1861 it adopted, by a vote of 166 yeas to 130 nays, the Ordi nance of Secession, and thus withdrew from the Union, in the exercise of the right of self-government asserted in the Declaration of Independence. This opened "Pandoras box," and a tragedy was enacted that Gen eral W. T. Sherman rightly named "helL"

On the twenty-fifth of October, 1865, another con vention of the people assembled at the same place. The environments were different. The slaves had been freed by force; the barns were empty; the fields, gardens and orchards had been trampled down; dwellings robbed; cities sacked and burned; live stock slaughtered or stolen; mills and factories demolished; churches pro faned and cemeteries desecrated; the flower of South ern chivalry dead; the land groaning in poverty, widow hood and orphanage; and crashed by the iron heel of a relentless military despotism; the people put under the government of military satraps. This convention, like the former, was composed of able and patriotic men. Herschel V. Johnson presided over its delibera tions and Charles J. Jenkins led them upon the floor.

President Johnson had adopted his plan of readjust ing the seceded States in their relations to the Union. James Johnson, an able and conservative citizen of the county of Mnscogee, had been appointed Provisional Governor, and the convention assembled for this pur pose. The Ordinance of Secession was promptly re pealed by a unanimous vote, the payment of the War debt prohibited and the emancipation of the slaves ex-

44

MEN AND THINGS

pressly recognized. The presidential program of recon struction was literally carried out. A State constitu tion was adopted in conformity to the Constitution of the United States. A general election for Governor, members of Congress and members of the General As sembly was held. Charles J. JenMns was elected Gov ernor.

"The pure of the purest,

The hand that upheld our bright banner, the surest." The legislature assembled on the fourth of December

and unanimously ratified the thirteenth amendment to the Federal Constitution, prohibiting the existence of slavery. Charles J. Jenkins was inaugurated Governor on December 19,1865, and Provisional Governor James Johnson relinquished the conduct of the State affairs to the authorities thus constituted. The legislature elected Alexander H. Stephens and Herschel V. John son United States Senators. The people supposed that constitutional civil government was restored, that mili tary domination would cease, and that they could persue their avocations in peace and hope, if in toil and poverty, but this was a mistake. The legislature met on November 1, 1866. The fourteenth amendment tov the Constitution had been submitted to the State for ratification. Governor Jenkins, in his message to the legislature, made a masterly argument against ratifi cation. The legislature declined to ratify by a unani mous vote in the senate, and by a vote of 132 to 2 in the house. Major-General John Pope assumed command in the third military district, containing Georgia, Flor ida and Alabama, on April 1,1866. Civil government

IfSN AND THINGS

45

having been restored and in successful operation in the State, Governor JenHns made an effort to bring the question of the constitutionality of the reconstruction act before the Supreme Court for adjudication. This effort failed. The State of Georgia presented the anomalous spectacle of being under two governments a civil government under constitutional law adminis tered by Governor JenMns, and a military despotism, in violation of law, enforced by Major-General John Pope.

On the sixth of January, 1868, Major-General George G. Meade assumed command in the third mili tary district. Congress had repudiated the Presidential scheme of reconstruction and adopted that provided in the several reconstruction acts; and impeached the President.

On January 11 the State officers were admonished under color of authority, not to interfere with the exer cise of military authority in the States composing the third district. Governor JenMns and State Treasurer Jones were ordered to pay out of the public treasury the public money, under military order, which they declined to do for the reason that they had taken an oath to support the Constitution, which provided that "No money shall be drawn from the treasury of this State, except by appropriations made by law. Where upon General Meade issued the following order: "Charles J. JenMns, Provisional Governor, and John Jones, Provisional Treasurer, of the State of Georgia, having declined to respect the instructions and failed to co-operate with the Major-General commanding the third military district, are hereby removed from office.

46

MEN AND THINGS

Brevet Brigadier-General Thomas H. Ruger appointed Governor and Brevet Captain Charles F. Rockwell to he Treasurer of Georgia." .

A constitutional civil government in a time of peace was thus summarily abolished by an order, on the ground that its officers refused to violate their official oaths and allow the treasury robbed, and a military despotism substituted in its place and the treasury opened to the robbers.

Under the congressional plans of reconstruction, a registration of voters, under the first civil act, was ordered, and an election for delegates to a constitu tional convention. One hundred and eighty-eight thousand six hundred and forty-seven voters, white and black, were registered. The white majority was about 2,000. The election of delegates was held from October 29th to ^November 3d. Of the delegates chosen, 133 were white and 33 black. John E. Bryant, of Skowhegan, Maine, was one of the whites, and Aaron Alpeoria Bradley and Tunis G. Campbell, from the southern coast of Georgia, were two of the blacks. This white and black spotted convention assembled in Atlanta, under the supervision of General Meade, made for Georgia the organic law, known as the Constitution of 1868. On March 14, 1868, a military order was issued for an election commencing April 20th, to continue four days, on the ratification of the Constitution, and for State officers, representatives in Congress, and members of the General Assembly, of which three Senators and twenty-five representatives elected were negroes. On July 4, 1868, "pursuant to General Order No. 98, is-

IfEN AND TSIN&S

47

sued from Headquarters, Third Military District, De partment of Georgia, Alabama and Florida, dated At lanta, Georgia, July 3, 1868," the Legislature met in Atlanta, and was organized by R. B. Bullock, under military order of Gen. Meade.

On July 29th, Joshua Hill and H. V. M. Miller were elected United States Senators. The fourteenth amendment to the Constitution was ratified, and all the conditions of Congressional reconstruction complied with. On July 28, 1868, the State was declared to be restored to the Union,

Upon examination of the Constitution of the State, no provision thereof expressly gave to the negroes the right to hold office; the negroes were therefore expelled from the Legislature. On December 22, 1869, Con gress passed "An Act to promote the Keconstruction of the State of Georgia." Whereupon JRufus B. Bullock issued the following order: "Atlanta, January 8, 1870. In pursuance of the Act of Congress (to promote the Teconstruction of the State of Georgia), approved December 22, 1869, it is ordered that J. W. G. Mills, .Esqr., as Clerk pro tern, will proceed to organize the Senate. He will call the body to order at 12 oclock k., on Monday, the tenth instant, in the Senate cham ber. The names of the persons proclaimed as elected members of the Senate, in the order of General Meade, dated "Headquarters, Third Military District, Depart ment of Georgia, Florida and Alabama, Atlanta, Ga., January 25, 1868, General Order 90. As each name is called, the person so summoned will, if not disquali fied, proceed to the clerks desk, and take oath or" make

48

MEN AND THINGS

affirmation (as the case may be) prescribed in the said act, before Judge Smith, United States Commissioner, who will be present and administer the oath. When the oaths are so executed, they will be filed with the Honorable, the Secretary of State, or his deputy, who will be present; when all the names mentioned in said order of General Meade, have been called as be fore provided, such of the persons as shall be qualified will thereupon proceed to organize by the election and qualification of the proper officers."

KTJFUS B. BULLOCK, Provisional Governor.

On February 15, 1870, the General Assembly pro ceeded to elect three United States Senators, after hav ing already elected two Messrs. Hill and Miller, who were in life, had not resigned, were at Washington applying for their seats, and whose term of service had not expired. But, of course, official oaths and constitutional obligations were cobwebs, with the ma jority of the Legislature. Poster Blodgett was declared elected for the term of six years, to commence on March 4, 1871. Henry P. Farrow was declared elected for the term expiring on March 4, 1873, and Kichard H. Whitely was declared elected for the term expiring March 4, 1871. Georgia had seven Senators in life, elected not one of whom had been permitted to qual ify, and take his seat. The patriotic members of the Senate entered upon the journals their indignant pro test. But Provisional Governor Eufus B. Bullock had the protection of Brevet Major-General Alfred H.

HEN. AND THIN&B

49

Terry, commanding the military -district of the State of Georgia.

On July 18, 1870, the Provisional Governor in formed the General Assembly that he had secured un official information of the passage of an act to admit the State to representation in Congress, and adding that he was informed that "the General commanding will make no objection to the General Assembly pro ceeding with legislation." The Governor and Treas urer, presented against each other, respectively, charges of high crimes and misdemeanors, which were investi gated by a joint committee of the two houses of the General Assembly during the months of May and June, 1870. The evidence, and the report of the committee, which appears on the journal of the General Assembly, establish the guilt of both. Reconstruction in the se ceded States, was a reign of falsehood, lawlessness, rob bery and despotism. It is due to a few able and patri otic members of that historic Legislature, to say that they made a manly and gallant stand for constitutional liberty and common honesty, for which the country owed them a debt of gratitude it will be difficult to diecharge. Finally the State was allowed representation in Congress. Gov. Bullock found it necessary to his safety to retire from the State before the expiration of his term of service. A new election installed an honest democratic administration.

In 1877, the people of Georgia held a constitutional convention, over which that incorruptible statesman and patriot, Charles J. Jenkins, presided; and estab lished a Constitution that secured white over black do-

60

If EN AND TBIVOS

mination, and restored the supremacy of the civil over the military authority.

The men who invoked, imposed and enforced Con* gressional Reconstruction upon a brave and patriotic people defeated in war in the anguish of grief, and thralldom of poverty, sacrificed honor, race and liberty for power and plunder, and have gone to history, em balmed in infamy.

CHAPTER VHI.

CoiromoHs AFTEB THE WAB LAWYEBS.

The reconstruction regime packed the judiciary, as far as possible, with judges in sympathy with their policy. That policy had greatly demoralized the pub lic sentiment. This was especially true in certain sec tions of the State. The people of the mountain region of the State were opposed to secession. They lived remote from cities and railroads, owned few slaves, made an honest living by hard labor, and distilled their corn and fruit without revenue. They did not care whether slavery was established or prohibited in the territories; the government was beneficent to them. They honored its founders, loved its traditions, and were proud of its flag. Their delegates in the conven tion were nearly unanimous in opposing secession. Several of their delegates declined to sign the ordinance after it was adopted. These people had bright intel lects, strong convictions and high prejudices. They were true and faithful in their friendships, bitter and relentless in their enmities, generous in hospitality, and full of resources in the execution of their purposes. When the war came they were divided. Most of them joined the Confederate, but some the Union army; and many sought to avoid service in either. During the war, Home Guards, representing both sides under the pre-

61

62

1IEN AND THINGS