Outdoors

Georgia

Septeipber/October 1977 $1.25

George Busbee

Governor

Joe D. Tanner

Commissioner

BOARD OF NATURAL RESOURCES

Donald J. Carter Chairman

Gainesville--9th District Lloyd L. Summer, Jr. Vice Chairman

Rome-- 7th District

Leo T. Barber, Jr. Secretary

Moultrie-- 2nd District Dolan E. Brown

Twin City-- 1st District Alton Draughon

Pinehurst-- 3rd District George P. Dillard

Decatur--4th District Mary Bailey Izard

Atlanta-- 5th District James A. Mankin Griffin-- 6th District J. Wimbric Walker

McRae--8th District Walter W. Eaves

Elberfon-- 10th District

Sam Cofer

St. Simons Island Coastal District Leonard E. Foote

-- Waleska State-at-Large

James D. Cone Decatur-- State-at-Large

A. Leo Lanman, Jr.

-- Roswell State-at-Large

Wade H. Coleman

Valdosta-- State-at-Large

DIVISION DIRECTORS

Parks and Historic Sites Division Henry D. Struble, Director

Game and Fish Division

Jack Crockford, Director

Environmental Protection Division J. Leonard Ledbetter, Director

Geologic and Water Resources Division Sam M. Pickering, Jr., Director

Office of Information and Education David Cranshaw, Director

Office of Planning and Research David Sherman, Director

Office of Administrative Services James H. Pittman, Director

OutdOOrS \t) Georgia

Volume 7 September/October 1977 Numbers 9/10

FEATURES

Prince of Game Birds

Charles Elliott

2

Legal at Last

Gib Johnston 13

Guns and Loads for Dove

Aaron Pass 16

Special Section: Hunting in Georgia

21

Acres for Wildlife

Terry Johnson 29

Set Your Sights

Aaron Pass 34

Hunter's Forecast

Aaron Pass 38

.... Hemorrhagic Disease

Daniel K. Grahl, Jr. 41

Georgia Hunting Regulations

45

DEPARTMENT

Outdoors in Touch

Susan K. Wood 48

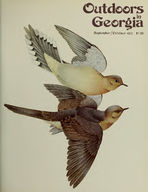

FRONT COVER: Dove painting by Dale K. Cochran. BACK COVER: Georgia's fall color. Photo by Mark Williams.

Phone-656-5660

MAGAZINE STAFF

David Cranshaw Aaron Pass

Editor-in-Chief Editor

Susan K. Wood

Bill Morehead Rebecca N. Marshall

Dick Davis

Bill Hammack

Rhett Millsaps . . .

Managing Editor

Writer Writer Writer Writer

Circulation Manager

Liz Carmichael Jones Michael Nunn Bob Busby Edward Brock Bill Bryant Jim Couch

Art Director Illustrator

Photo Editor Photographer Photographer Photographer

Outdoors in Georgia is the official monthly magazine of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, published at the Department's offices, Room 714, 270 Washington Street, Atlanta, Georgia 30334. Publication Number 217140. No advertising accepted. Subscriptions are $5 for one year or $9 for three years. Printed by Williams Printing Company, Atlanta, Georgia. Articles and photographs may be reprinted when proper credit given. Contributions are welcome, but the editors assume no responsibility or liability for loss or damage of articles, photographs, or illustrations. Second-class postage paid at Atlanta, Georgia. 31,000 copies printed at an approximate cost of $16,500. The Department of Natural Resources is an Equal Opportunity employer, and employs without regard to race, color, sex, religion, or national

origin.

Change of address: Please allow 8 weeks for address changes to become effective. Send old address as well as new address (old mailing label is preferred).

New dear's Resolutions -

A Bit Early

By now, you've probably noticed that this issue of OIG is a bit thicker than usual. It con-

tains 16 additional pages this month, or should

we say months. For this is the September/Octo-

ber issue of Outdoors in Georgia. We have com-

bined two issues into this 1977 Fall Hunting

Edition.

This enlarged issue is in many ways a prece-

dent of things to come. We are now trying some

new ideas that we hope will improve an already

-- good product. Improve it in a way that you

the subscribers will approve and enjoy even

more.

Before I enumerate these proposed changes,

let's mention those things that this issue does not

signify. One is that we are not planning to start

a bi-monthly magazine. This is our first bi-

GAME monthly issue since the first days of

&

We FISH in 1966 (it was a quarterly).

intend

to maintain our regular monthly publication,

however, this fall we had to face realities. The

realities of a tight budget, of staff reassignment

and of being late all year finally caught up with

us. It became apparent that there was no way

we could get back on schedule without drastic

measures and we view the combination of two

We issues as that drastic step.

have made it our

-- primary goal to get back on schedule during

1978 sort of an early New Year's resolution.

We may not make it on time every month next

year, but we will do better.

Now for some positive changes. This issue is

our first attempt at an expanded format since

July 1971. This is something we see very defi-

nitely in the future. Admittedly this combined

issue made this expansion possible, but we are

definitely planning more enlarged monthly is-

sues. We are charging you more for the maga-

zine this year; it's only fair that we give you

more.

We also plan to deliver more in the way of

stories and photos. Last year we conducted a

readership survey which gave us a better idea of

what you wanted to see. In 1978 you will begin

to see it. More stories of substance about Geor-

gia, her natural resources and their manage-

ment, more hunting, fishing, and outdoor rec-

reation, more things to do and places to go for

the reader. These plus some other new concepts.

These are not really changes in OIG's direc-

We tion, merely a refinement of it.

are not going

to be different, but we are going to be better.

The differences will not happen all at once but

gradually. We hope you like our direction and

-- we hope you will give us your opinions good

and bad. That is the way we make sure that our

direction and yours is the same.

OiLtrv^. 14^4

Septerpber/October 1977

prince ofGame Birds

By Charles Elliott

IJie picture could not have been more

striking or colorful even in oils by an Old Master. But this was no dead scene to be studied in detail, no tableau of frozen life, but rather a living, breathing drama against a tapestry of golds and greens and azure, and tense with

expectation.

Two immobile pointers, one the color of old

ivory and the other a lemon and white backing a few yards away, stood with heads and tails high, the essence of concentration. Beyond them in the golden sedge we knew that a covey of bobwhite quail crouched against the ground, aware of our approaching footsteps that momentarily would explode them like fragments of a brown bombshell into an unpredictable

pattern.

I licked my lips and gasped for an extra breath of air. The man whose pulse does not

beat a little faster and whose systolic pressure does not jump a point or two under these circumstances is better off playing dominoes in a

monastery".

We walked slowly on, our gun barrels pru-

dently angled skyward, our fingers ready to reach for the safety catch and then the trigger

when the birds' legs and powerful wings catapulted them out of the grass.

The point was perfect; the quail covey left

the earth with a roar. In keeping with the un-

written rules of quail shooting, my partner on

the left concentrated on the covey segment that flew in his direction and I picked out a bob

barreling to my right. Just as I put my line of

sight on him and swung for the proper lead

that would let my shot string engulf him in

flight, he disappeared behind the brown trunk

The following is Chapter One of the 1 93-page book, Prince of

Game Birds: the bobwhite quail published by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. & 1974

Bob Busby

of a tree. I needed a fraction of an instant to pick up another white-throated male and this

one was in the open. My lead was right and my

A second choice folded neatly in flight. clean kill.

The pointer closest to me had seen my bird

go down. At a word, he broke point, raced to where the bobwhite lay belly up on the carpet

of brown grass, picked up my trophy with a

gentle mouth, brought it back, and lifted his head until I could take it out of his mouth. Then

he looked up at me and laughed as only a happy

dog can.

My partner had taken out two birds on his

side and the other dog brought them back with long, bounding strides. With the gun in the crook

of his arm, my companion held up the brace of

bobs and admired them. "I saw generally where the singles went

down," I said. "We've got enough birds out of the covey

for this trip," he replied. "Let's save the rest

Outdoors ip Georgia

for later and try to find another bunch."

He again looked at the quail in his hand. "No doubt about it," he said, "This is the prince of game birds."

The dogs took off again in a rhythm of their own that covered the winter woods as far as we could see ; we followed more leisurely, skirting the far edge of the field and hillside where leafless trees marched down to the rim of a narrow swamp.

"The first bird that I put my gun on ducked

behind a tree and flew straight away," I said. "I'd probably have missed him anyway."

My partner, who had followed the bobwhite

coveys all of his mature life, chuckled.

"Ten to one," he said, "that if we could

prove it, we'd find that he deliberately put that tree trunk between you."

"Do you think," I asked, "that any bird has

got that much sense? Wouldn't it be instinct

instead ? '

Septen?ber/ctober 1977

Bob Busby

He looked at me like he was putting his

sights on the tail feathers of a bobwhite rooster.

"No sir-ree. You writers and technical peo-

ple harp a lot about the instinct of critters, and

to a certain degree you may be right. There's

a very thin line between instinct and intelli-

gence anyway. From more than fifty years of

chasing after quail, I know the bird is smart. I've seen them pull stunts that I couldn't attribute to anything but thinking their way out of a tough spot and you have seen it, too."

I assured him that I had. I remembered that on a plantation where I had hunted often, there was one covey that always flew toward the hunting wagon, horses, and handlers when it blasted off the ground. Somehow the birds had learned that we would not shoot in that direction. The occasional stray that deviated from this pattern was gunned down, but the bulk of the covey knew the direction in which

their safety lay.

It might be instinct that makes a covey lie close against the earth when the dogs are staunch on point, but someone smarter than I will have to decide whether its thought processes are working when the quail runs for a nearby thicket so dense that when it does take to the air, the odds are very much in its favor. I'm sure also that it is more than instinct that

inspires a covey or a single bird to fly almost out of sight, set its wings as if it were going back to earth, then over a little rise, or beyond the cover of trees or brush, pick up again and fly another hundred yards. These are only examples. There are hundreds of others.

Intelligence, however, is only one of the factors that makes the bobwhite quail the beau

ideal of game birds in those states where it is abundant. Another is the generous hunting season, which is longer than for most other game. The Georgia season usually runs from some-

time near Thanksgiving to the end of February. The bobwhite is one of the most popular of

all game species with the wife of the average hunter. After years of living with a man who

stayed out all night after raccoons, opossums,

or foxes, who got up in the wee small hours to make long drives to some distant spot for a dawn hunt for deer, ducks, turkeys or whatever, a friend's wife asked him, "Can't you

guys find something to hunt that doesn't get up in the middle of the night?" She was a bit

more affable when our hunting activities revolved around quail. Although we sometimes made early starts to unfamiliar territory so that we could locate coveys by hearing their dawn calls before they left the roosting site, we ordinarily got away after the breakfast hour, which would put us in the field after the dew or frost had gone and the coveys had moved around and left enough scent for the dogs to find them. The morning and late afternoon hunts were always more productive, but under good field conditions we could find quail throughout the

day.

There is something special about each type of hunting that separates it from all other kinds : this usually centers on features peculiar to the species of game. Deer hunting and camp-

ing may go together, as do boats and blinds and big water for geese and many species of

ducks. With quail it's pointing dogs and brown fields and winter woods.

The prince of game birds has many traits that put it in a class all its own. To say that

speed and strength of wing are among these characteristics is not saying enough, for many birds fly faster and others have greater ma-

neuverability. But the quail's explosive takeoff and ability to get beyond range thru the thickest of tangle leaves even the most expert wingshot breathless.

Perhaps the most distinctive habit that helps to stand the bobwhite at the head of his class as the most popular of upland game birds is that of crouching against the ground and remaining motionless only feet and sometimes inches from the nose of a dog, until a hunter towers Over and almost steps on him. It is true that some of the other game birds as the woodcock, ruffed grouse, and on occasion the ring-

neck pheasant will hold this way to a point, but

such birds usually occur in singles, so that the gunner has only one target on which to concentrate, instead of the quail covey's explosion of bodies.

When danger threatens, the birds in a covey

flatten out and conceal themselves as nearly as possible in whatever cover they happen to be using at the moment. Herbert Stoddard, who

is the most noted authority on quail, told me

long years ago, even before his great book The Bobwhite Quail appeared, that this trait results from the birds' association with the Cooper's hawk, one of the quail's most persistent predators. The scream of a hawk, or the

sight of one, usually freezes the birds into immobility. Their coloration is so blended into the terrain that not even the sharp eyes of the

hawk can spot a bird on the ground. Woe to

the individual bob or hen that panics, for it is likely to end up in the stomach of the raptor.

But the bob's holding to a point is not a hard and fast rule. As every hunter knows, some birds in the same area will hold while others will run instead of crouching, especially where

A the cover is thin. "false point" often means

that the birds have moved on. More than often, if they stay on the ground, a good dog can find them again, and where the cover is dense enough to hide them, they may hold to a point.

I am probably typical of the quail-hunting

clan, especially the older members who have been at it for decades. One of the pleasures in

the hunt is watching good dogs at work, another is enjoying the charm of a Southern winter day, and still another is relishing the fellowship of companions. But the greatest pleasure of all is experienced in that tense moment when

Outdoors ip Georgia

the dogs are on point and I walk in with a

measured tread as though each step were the

My last I'd ever take.

throat is constricted and

I may even be a little uncertain on my feet.

Even after fifty years, that is what walking up

to a pointed quail covey does to me. Most old-

time quail hunters feel the same way. You might

think we'd quit abusing ourselves in this man-

ner and take up some other less nerve jangling

outdoor pursuit. But there is no cure for

bobwhite-itis, once you are infected with the

disease.

There are two reasons why the quail hunter is so tense. One is that he doesn't know exactly

what is going to happen, and the other is that he does know. If the covey hasn't flushed wild

before the hunter comes in sight, or run off from the dogs, he knows that every step he takes should trigger some violent action. It's

like holding a lighted stick of dynamite ; it could go off at any second.

Septen>ber/ctober 1977

The dynamite explodes; although lie knew

it would, tlif hunter is never quite ready for it.

The birds are in the air and the sound of wings

drums against his ears. He must pick one bird

out of the bevy, because aiming in the general direction of the group and pulling the trigger

is a sure way to miss. If the hunter's got a quick, sharp eye, he may be able to select a white-

throated male, or sec two birds crossing at a focal point and try for both with one shell.

There is no fixed pattern to a covey rise. Each one is different from the last. In a thicket, the

bobs and hens may dodge through trees or

flare upward over the topmost branches. In the

open they may fly away in a bunch or scatter

in all directions. At times they've gotten off

the ground and barreled so straight at me that I've had to duck to keep my hat from being

-- knocked off or so I thought.

The covey's gone. If the hunter has kept his equilibrium and poise long enough to get off an effective shot or two, he may have one or a

brace of quail on the ground.

Many nimrods I know prefer single bird

shooting over the covey rises. "It's one against

one then," an old swamper told me, "and I got a better chance than when I take on the

whole bunch." If he is experienced with quail, a sportsman

will get in his blows on the covey rise and then watch the singles down, or if they fly out of sight, he at least knows the direction in which the majority of the covey has gone. The birds

may scatter when the covey erupts, but usually

a large percentage fly in the same direction and go down reasonably close together. There

is no set distance of flight. It may be a hun-

dred yards into a thicket or swamp, or the

birds may fly a quarter of a mile or more

through fairly open territory. Single bird shooting is another of the dis-

tinctions that give quail hunting a flavor all its

own and make it different from almost any other type of wing shooting. If the birds get up out of range or the hunter's shot strings go

astray on the covey rise, he almost always has chance to redeem himself.

Although the hunter marks the location where he has seen the singles scatter out and go to

earth, finding them again may not be quite as simple as it would appear. Some speculate that

the air flowing against a quail in flight washes

much of the body scent out of the feathers and when' he hits the ground he may either run a

Outdoors ip Georgia

short distance to more suitable cover or burrow

into the vegetation on the spot and be com-

pletely hidden. Maybe there is some substance

to the idea because I have often wondered if my

dogs had suddenly lost all sense of smell, when

after much kicking and stomping around I've

been startled by a bobwhite who has flown out

of the grass under my feet from a spot the

dogs had covered half a dozen times.

Another mystery for the experts to solve is

why one day a man can find a dozen or more

coveys of birds on a morning hunt, and a couple

of days later he can't get one point or raise

one bird over the same course. We know that

-- quail are not tourists not to a great extent -- at least but how a hundred birds can simply

vanish in two or three days and then appear

-- again a few days later

when scenting and

-- other conditions have remained the same has

many a hunter pulling at his wig.

Quail shooting is ever and eternally full of

surprises. Even false points by the dogs have

their moments of anticipation. No matter how

keen a nose the four-footed hunter has, or how

much bird sense, there are times when he may

be completely fooled. Several creatures must

carry odors very much like that of the quail ; an

example is one of several species of small

sparrows that live in vegetation close to the

ground. Every hunter has seen his brag bird

dog swing and freeze so suddenly on point that

he might have been looking a bob or hen right

in the eye. Many's the time I've walked up to

such a point with my throat tight and my pulse

pounding, only to flush a wisp of a sparrow

out of the grass. In the parlance of the seatter-

gunner, these are known as "stink birds." The

old pointer or setter thus hoodwinked is ob-

viously embarrassed, and will nose around a

bit more as if to insist, "Well, a quail has been

here sometime", or he'll look up with his eyes

rolled back as if to say, "Sorry, boss. I guess I

goofed. '

I owned an ancient pointer with an excellent

nose. With anything that smelled like a quail

he never took a chance, and sometimes when

he'd get going on the stink birds, you'd think

he had forsaken quail forever. The little stinkies

must have smelled mighty good to him, but

when one would dart away in front of his nose, lie was ham enough to try to laugh it off. He'd

roll out his tongue, look up at me with the most

ludicrous expression, and wait for any invec-

tives he must have thought he deserved. But

Septen?ber/ctber 1977

I'd only shake my head at him and he'd bounce

a couple of times as though it were a brand new ball game and take off in any direction he

-- thought a covey might be or another stink

bird.

A creature that must smell good to a dog is

the terrapin, or "gopher," as he is known in the southern part of the state. Dogs often point one of these and there is some question as to whether they really confuse it with a quail or just like the smell. Occasionally a dog will gal-

lop back to its master or trainer, proudly bearing a terrapin in its mouth as if to say, "Here's something that tastes better than a bobwhite."

But all these are merely little side excitements of the hunting day. The real drama begins when the dogs are down in such a way that they know, and the hunter knows they know, that a covey of bobwhites crouches in front of them, alert and ready to take to the air. If the hunter is a bit slow in getting up to the point, the birds

may have scurried off just far enough to flush wild and make any shot either impossible or

most difficult.

On the other hand the birds may lie so close

that the hunter is in the middle of the covey before it flushes and goes off to all points of

the compass. At such a time it would seem easy to down a bob or hen with each shell in your gun. But the careful shooter must pause long enough to see where the horses or vehicles stand, where all dogs and companions are located, to make sure that the bird is in the clear with

nothing in front of it but trees, brush, or open space. One can usually count on most targets being in a safe spot, but it doesn't pay to take

a chance.

Occasionally a covey is smart enough to flat-

ten out and let a brace of men march right through it and beyond. Then it roars off the ground and flies away behind the party. This is by no means an unusual maneuver.

Another one that no hunter, as far as we know, has ever explained is how completely a mass of single birds can disappear, without leaving a trace. Often the fields and woods are open enough and the visibility good enough to pinpoint the birds when they go down. But as

far as finding even one single is concerned,

those quail may as well have flown into a gopher

hole. The dogs can't smell them and tramping back and forth through the area won't flush even one bird.

If a fellow spends enough days hunting, this

V

li&U

Bob Busby

Outdoors it? Georgia

happens numbers of times in the course of a

season and never fails to leave many a sportsman trying to solve the puzzle. I was hunting

with a friend on his south Georgia plantation

where over many years he has maintained a maximum population of quail. Finding several

coveys around a field or in one strip of woods was not unusual, and once on a covey rise two more groups of birds got up at separate points

and flew with the covey we had flushed. We

stood and watched them go down in an open wooded area about 300 yards away.

"We should get some mighty fine single shooting out of that place," my host declared.

On our way to the spot where the birds had landed, we rode up a fourth covey, which flew

into the same strip of woods. "That head must have a hundred quail in it,'.'

I exulted. "Hope we've got enough shells."

We walked into the woods, our guns ready.

The dogs went ahead of us, casting back and

forth to cover every quarter-acre in that flat.

We spent a good half-hour there, tramping out

every bit of the dense cover, with the dogs ranging around us without getting a point or having the first bird flush anywhere in sight.

Even if the quail had hit the ground running and pulled the old military maneuver known as getting-the-hell-out-of-there, some of them at least should have left enough scent to be trailed. But those four coveys simply vanished without having a grain of powder burned at them.

This is one of the mysteries of quail hunting

that makes it such a fascinating sport. More

often, of course, the singles are there to dish

up a brand of gunning that only a bobwhite in flight can provide.

In a covey, the bird that has always intrigued

me and a lot of other nimrods is the "sleeper." No one has ever been able to tell me whether this is the most stupid member of the family

group, or one of the most intelligent. Often, after the covey rise, with the bang-bang-bang of the shooting, the yelling between hunters, the bounding of dogs to pick up dead birds, and the general tumult in this climatic moment of the hunt, one bird will roar up in the middle

Septerpber/October 1977

of all the confusion and fly away with dogs and hunters looking open-mouthed after it. If anyone ever comes up with the explanation of

the sleeper tactic, all of us old quail hunters would like to hear it.

One of the charms that makes quail shooting special is that it's a "team" sport, whether we're talking about the lone hunter and his dog

or the social ritual of plantation hunting with horses, handlers, and several shooters.

No other type of shooting gives a man such

rare fellowship with his dogs, which are an integral part of the hunting team. It's true that where quail are plentiful, an outdoorsman

versed in the habits of this game bird could walk alone and in the course of a day find a few bobwhites on his own, but this is the most difficult kind of hunting I know; the lone

hunter is lucky if he can stumble on one or two coveys. The pointers, setters, shorthairs, what-

-- ever breed is used the dogs add a whole new

dimension to the rewards of the hunt. The greatest satisfaction any quail hunter

can have is teamwork with a well-disciplined dog that he himself has trained from a puppy.

He knows the animal's personality, its strong

points and faults, just as the dog knows him and will respond to his instructions, whether they are given by whistle, hand signal, or voice. The fellowship with his dog or dogs and watching them work is one of the things any outdoorsman looks forward to as much as pulling the trigger on his gun.

Dogs find birds either by catching scent borne on a wisp of breeze or clinging to the low vegetation through which the quail have fed. Some dogs are considered "winders." They go to a covey with head held high, following the thread of body odor. Other dogs, the "trailers," work more slowly along the scent trail left by the covey on the ground. To watch either type of bird dog cast back and forth and work out the

scent pattern is one of the joys of quail hunting.

One of my dedicated quail-hunting partners,

who is even a few years older than I, thinks that

most hunters these days do not feel as close to their bird dogs, or know them as well as the

---

y-*

older sportsman did a few decades ago. "Then," he said, "it was like having one

of the family around. He had the run of the

place, and there were no sixty-mile-per-hour automobiles to run him down if he ventured into the street. In the evening, around suppertime, he'd come in and lie down by the wood fire on the hearth and act the gentleman in every way.

Two or three times during the season, I'd catch

a train to south Georgia to hunt with a friend. They let the dog ride in the railway coach with

me and when we got there, he stayed in my

hotel room. In those days I was not only better

-- acquainted with my hunting dogs I had the

best I've ever owned."

Some of my younger friends still have almost

the same association with their pointers and setters, except now it is usually necessary to

-- -- keep the dogs for their own safety confined

to kennels or on a chain in the back yard. But in the field a dog is one of the team, as a friend and as a part of the hunting ritual.

As one of my old swamper buddies observed, "A dog is like a people." Each, naturally, has

his own distinct personality, with all the traits or character any human might have, and a bird dog is no exception. One dog will tackle any

kind of a briar thicket if he thinks quail are there and the next explores every route around

it. One animal finds pleasure in gently retrieving a dead bird and the other chews it flat, no matter what the training or admonition. Most bird dogs have a passion for chasing a rabbit; with some it's a mania.

10

Many times I hunted in the southern part

of the state with a friend whose dog was an inveterate cottontail chaser. There seemed to be no breaking him of the habit. The farmer whipped his dog with the dead rabbit, stuffed it half down the animal's throat and almost choked it, and even hung the bunny around the dog's neck until it was putrid. In exasperation

he started shooting at his pointer every time it

jumped a rabbit, but was careful the dog was far enough away so that the No. 8 pellets would do no more than sting its hide.

The pointer didn't give up its rabbit chasing, possibly because it had become an addiction, like smoking or drinking. But after the first few shootings, the dog was smart enough to

stay out of range of that shot string. If he

found a rabbit in the bed, or if one jumped up in front of him, the dog paused only long enough to look back and see how far away his master stood. If he were within shotgun range, the pointer passed up the chase. Out of range, he was gone like a bullet and all we could do was sit down and wait for his return.

A dog's personality, as well as the intelligence

and unpredictability of the birds, adds up to one more reason that quail hunting has a flavor all its own.

Just as it does in most outdoor pursuits, quest of the bobwhite brings out the mettle of any man. If you want to see what sort of fellow a

man is, take him quail hunting. Watch his reactions when he's wading knee-deep in briars, when the dogs false point, when the quail don't fly his way and the hunter or hunters with him seem to get all the shooting, when he misses, and when he hits. Under these emotions he can

no more hide his basic character than he can

hide the color of his eye.

I made one quail hunt with a fellow; just one. I was on the verge of going into a business deal with him. In his home and mine he was a gra-

cious host and guest ; at a luncheon or dinner

he was the epitome of charm. He was a success-

ful businessman and our venture together looked promising. While not a dedicated hunter, he was familiar with a gun and had been in the fields and woods on occasion. I arranged

a hunt with my potential partner at one of my favorite quail-hunting places and he accept-

ed the invitation with great enthusiasm.

It was one of those cerulean days with a touch of frost at dawn and a bite to the wind that

made a fellow want to walk to warm his blood

Outdoors ip Georgia

and breathe deeply to clear his lungs. The dogs were alert and ready for action. They started out as though they intended to find every quail in the country that same morning.

Our first point came in the edge of an old field that ran along a narrow creek swamp. The

dogs held steady and sure. I was ahead of my

companion so I waited for him to catch up, and we waded in. The covey blasted off and I concentrated on that segment of the group that

angled away on my side. I folded one, swung

almost 45 degrees, and got another just before

it reached the swamp thicket.

"I got two," the guy yelled. "Great," I said. "We're off to a good start." Without waiting for the dogs, he raced over and picked up the first bird I'd shot and when

the pointer brought back my second bird, he

took it and said, "That's the other one."

Now a fellow knows when he makes a kill on any bird. He leads it right, pulls the trigger and,

allowing for the split second or so for his shot string to reach its mark, sees his bird go down.

It was conceivable that my gunning partner and

I had shot at the same bird that first fell, but if he had made a try for the second, he'd have

-- blown my hunting cap off or worse. When he

ejected only one spent shell, I knew the answer. "Nice shooting," was about all I could think

of to say.

That was the prophetic beginning of a most disturbing day. This guy, so gracious in the drawing room, seemed to lose all sense of values in the field. If he were nearest the dogs when they pointed, he didn't wait for me, but waded

-- right in and flushed the covey and usually

missed. When we shot together, he claimed the

birds on the ground, though a couple of times

when three went down, he did admit that perhaps I had been lucky enough to bag one of

them.

I really didn't mind all of this too much. I wanted him to enjoy the shoot, but some time after the middle of the morning when the action slowed down and he began to tire, he cussed the briars, the brush, and when he began to take his

feelings out on the dogs, I called it a day. I

didn't know how long it might be before he would start on me. You don't have to guess twice to know that I found an excuse to back out of the deal on which we had planned to work

together.

No doubt about it. Quail hunting brings out

the character of a man.

September/ October 1977

Prince of Game Birds: the bobwhite quail can be purchased through DNR's Office of Information and Education. The price is $5.50. Send check or money

order to Bobwhite Quail, Department of Natural

Resources, Room 719, 270 Washington St., S.W.,

Atlanta 30334.

Certainly not the least of the allurements

which make quail hunting special is the season of the year. With the exception of a few winter days when icy winds scour the countryside and

cold rains beat through leafless trees, Georgia weather is generally bright and cool enough to

be exhilarating and to make any man glad that

he can be outdoors behind a pair of eager hunt-

ing dogs. The green world of summer and the kaleidoscope change that came on its heels have faded to softer hues of brown grass and golden

sedge against an emerald background of pines and darker green live oak clumps in the more

southerly latitudes. To any dedicated quail

hunter this is the finest season of the year.

T. Craig Martin

11

!

i

1

.

w

;>

- 1 fa .i^A/i at ' _'

mv 1

. J-/. '

^> f

jt&

5&t.\

';'

<*

\

M

> M^H

Outdoors ip Georgia

the compound bow

By Gib Johnston Photography by Bob Busby

As most hunters know, Georgia has become the last

state to legalize the compound bow. It can now be used

wherever bows are legal. Many hunters have hotly de-

bated the wisdom versus stupidity of the state's hesita-

tion on the compound bow, but it doesn't matter now.

HB It's the law. Section 45-503 of

792 as passed by the

1977 General Assembly says:

"Legal Weapons. It shall be unlawful to hunt

wildlife with any weapon except the following:

(a) Long bows and compound bows for hunting

deer are permitted only during the regular hunting

season and during the archery season for deer,

provided such bows have a minimum recognized

" pull

In the numerous requests and demands for the legali-

zation of the compound bow it was said, in most glow-

ing term, that this is the ultimate bow, that it shoots

straighter, harder, further, flatter and better than any

bow ever invented. We heard about how many more

deer would be taken, how fewer would be wounded,

how much easier it is to aim properly, how normally

poor archers would equal Fred Bear's skills, etc., etc. If

all or even some of these claims turn out to be true, then

it is correct; this is the ultimate bow.

However, it seems that the ultimate bow has been

invented before. Let's look back a couple of thousand

years or so.

No one will hazard a guess as to when the bow was

Septenjber/October 1977

invented. Reasonable evidence indicates that man has been hunting with a bow and arrow for more than 8,000 years. More food has been taken with this weapon than

with all firearms.

The ancient armies of the Hittites, the Assyrians, the Medes and the Persians had their archers; the expression "a parting shot" came from the practice of Parthian archers shooting from the rear of chariots as they fled a

battle scene.

Truly the bow was the ultimate weapon. With this bow it was possible to kill an animal (or man) without close contact with him. The distance achieved was much greater than was possible with sling or spear. Some

sages probably envisioned that this strangely curved

weapon would destroy the human race. But man found he was able to protect himself from

man, hence the invention of chain mail, a steel mesh

garment that made the wearer arrow-proof. Bowmen

no longer had the upper hand. Then around the 12th century, the cross bow came onto the scene. Again the "ultimate" weapon was at hand, and mankind was again doomed. The short bolts (arrows) from the cross bow could easily penetrate mail, horseman and horse, with disgusting ease and serious results.

The next evolution in this mad arms race saw the advent of the "knight in shining armor." Armored suits made of plates of solid, but thin, steel again made the mounted warrior the most fearsome warrior of all. The

Equipment and tackle courtesy: Georgia Archery and Sport, Athens, Ga.

and Ben Pearson Archery Company

longbow was his weapon. The cross bow, although

-- powerful, was slow capable of only three shots per

minute as opposed to the 12 plus for a longbow. Sometime before the 14th century, Welsh peasants

developed what was to become known as the English Longbow. It was a powerful bow. It could drive an arrow through a 3Vi inch oak door and would pierce the armored leg of a knight, go through the saddle and blanket and end up somewhere deep on the horse's side.

A good archer was expected to put 12 arrows in a

target 240 yards away in one minute. The ultimate weapon?

So, for centuries one or the other variation of the

bow has been "the perfect weapon." The Turks among others invented a method of laminating bows with horn, making light, yet powerful bows that were capable of

propelling arrows 800 yards upwards. During this period

the bow became useful more as a sporting weapon, since the advent of gunpowder had started the demise of the bow in warfare. Yet in 1964 the Purple Heart was awarded an American soldier for arrow wounds received

in combat.

-- The recurved bow a bow that, when drawn, bends -- the tips away from the archer came about sometime

early in this century. It was also an invention of the

Turks. Several modifications of this recurved bow followed, but nothing really new was developed until the middle of this century when the compound bow was developed. At last (and again), the ultimate bow.

Now hunters are divided in their opinions of the

latest in ultimate weapons. Before this goes any further, and if it hasn't already

become obvious, I am not a fan of the compound bow. They are ugly. They remind me of a fine fly rod with a

power winch. With all the advance geometry and

physics involved, I don't see how anyone can still classify any of them as primitive weapons. Seems to me that

dragging one of those things, with the extra strings and wheels through anything but an open field would be more than I would be up to. It would probably take 20 minutes to clean the limbs and leaves out of the mechanism. Granted, as far as Rube Goldberg devices go, it's

a beauty. But to me real beauty is the graceful lines and subtle geometry of a good recurved bow. The recurved

-- bow just looks like something to hunt with not a thing

with which to impress your friends.

14

*

-

***

\ a.

v r ~~ i

--; *

w

QK& \1

C -^'Jl

^MritmW^^ ^v^^bS" TMif%&Mtf

But that's just my opinion. Yours will likely differ

and that's fine, too. In the interest of impartiality, I have spent a good

many hours over several weeks shooting compound

bows. I've used all kinds, from the most complicated

and expensive to the most simple. And you know, those who clamored for the compound bow were right. The

shooting characteristics of these bows are super. This

was not my first time with the compound bow, but it was my first time for some serious shooting wtih the newly legalized weapon. And I finally got so I could get decent groups. The contrast between the two types of bow takes

some getting used to. The flat trajectory and the increased speed are the most noticeable features other than the confusingly soft pull. In short, I like the way these monsters shoot. But I don't like it so much that I'm willing to pay the necessary price for a good compound.

With archery deer season approaching, many long-

time bowhunters will, at last, be legally enjoying using

the compound bow for hunting, and many hunters will be taking up the bow for the first time.

Outdoors it? Georgia

An adjustable eccentric wheel and an Allen wrench

used for adjusting it. These provide for the tinning and turning of compound hows for correct roll-over and a change in the percentage of weight reduction. Note the tinning marks on the wheel.

A bow press is used to hold and compress a compound bow for modifications and adjustments.

September/October 1977

Hopefully these hunters have not been taken in by all the wild claims that have been made about the wonderful attributes of the compound bow. It, like any

other bow or weapon or tool, is no better or worse

than the user. So, practice those spectacular shots

you've been told are possible with the compound. They

are possible, but it's up to you. No matter which type of bow you use, there is absolutely no difference on the

deer end of the shot. The arrow must hit the right spot. There is no guarantee a new compound bow will

A make you a better bow hunter either. study done by

an archery shop in New Jersey and published in Archery World magazine shows that since New Jersey legalized the compound bow three years ago, 67% of the hunters

have gone to the compound, but there are no more deer being killed by archers. Hunter success is about the same; the number of deer taken by first time hunters are about equally divided between recurve and compound shooters.

As for those long shots you're looking forward to making, you might be interested in the new world

record, set last September. In flight competition (for distance only) an arrow was shot 1077 yards, 3 inches.

The bow? It was a hand held, recurved bow. This mark was about 100 yards better than the best distance scored by a compound.

In the competition using hunting broadheads, the

compound was able to better the recurve by a whopping 26 yards. (459 yds. 2 ft. 8 in. to 433 yds. 1 ft. 9 in.) These bows were in the 80 lb. class.

Archery stores and sporting goods shops these days have a myriad of compound bows available. The prices range from a modest $65 to well over $250, so caution

is in order. When you shop for that dream compound bow, or any bow for that matter, find a store with a

bowhunter on the staff, and insist on good, firsthand advice. Ask to shoot the bow. Test drives are always in order. If it's what you like and want, buy it! Don't waste time trying to use your old arrows, get new ones that are matched to the bow. Then go home and practice.

It's only a few weeks till the archery season, so there is precious little time to become familiar with your new bow. Only through hours of shooting can you hope to approach the capabilities of the bow. Only a good

^ archer can be improved by a good bow. Your bow and

arrows are up to the job. Are you?

15

-

i

>

vV

.

\

'

I

-*

r

^

*k

! -

1

-

-, ;*

/i

* -'

,.

Loads for Dove

Bv Aaron Pass

--

The mourning dove "mourning" from its mournful, cooing call and dove from the German, meaning dark-

-- colored bird is one of the most popular game birds in

the South. The origins of its name give no clue to the

tremendous attention this "dark-colored bird with the mournful call" attracts each fall with the opening of dove season.

Not only is the dove popular; it is democratic. It is favored not only by the powerful and influential, but also by anyone able to afford a shotgun and a fair number of shells. Thus the traditional opening day of dove season in early September finds bankers and butchers, industrialists and shop keepers, and politicians and plebeians all squatting in a film of sweat, under skimpy shade, being bitten by the same bugs waiting for the chance to shoot at dark-colored birds.

The main reason for this egalitarianism is the difference between the dove and its habitats and the more traditional game birds. Quail exist in comparatively low densities on large tracts of land and successful hunting depends on limited competition, good dogs and access to good habitat. Doves concentrate in feeding areas,

Bob Busby

This line-up should tickle any dove hunter's fancy.

From left to right: Semi autos; Remington model 1100, Browning model 2000, Franchi 520 (also shown

X above), Winchester Super model 1, SKB 300XL,

pumps; Remington model 870, Ithaca model 37, over/under; Browning Citori.

Septerpber/October 1977

dogs are not necessary (a good retriever makes things much more fun) and the more hunters (up to a point)

the better to keep the birds moving. Few people can

afford an exclusive quail lease, but almost anyone can afford the daily rate for a dove shoot.

Also while the brushy "left-out" fields and edge so important to quail are declining in this era of big business agriculture and forestry, doves don't mind the big fields and stands of pine trees. These elements are quite compatible with the doves' needs.

There is little of the traditional mystique and snobbish hoopla associated with the accouterments of dove hunting. There are quail hunts where the absence of a necktie might not lead to expulsion but will raise eyebrows. Dove shooting is not so demanding. About the only way to violate the dress code of a dove field is to show up in white T-shirt, a red football jersey, or some other colorful attire that spooks the birds.

Seldom are the super-light doubles of the quail field seen at dove shoots. Even the affluent shooters show up with workhorse autoloaders or pumps. The reason is pure practicality. Dove fields, when they are good, mean lots of shooting in an afternoon, and the light guns, particularly fixed breech doubles, deliver a lot of punishment backward in the course of 50 or 60 shots. Most popular dove guns are the recoil buffering gas operated autoloaders, and next are the sturdy pumps whose weight is a compensation for recoil. More and more over-unders are seen since the choice of two chokes is sometimes desirable.

The argument over the optimum gauge for dove shooting (and for other wing shooting sports) is an old one and will probably go on and on. The truth is all popular gauges, 12, 16, 20, 28, and even the diminutive .410 will reliably kill doves. It is just that some do it more reliably than others.

There are dove shoots restricted to .410 caliber shotguns only. These are the supreme test of wingshoot-

ing ability, because it is damn difficult to hit anything moving with a .410. Its small shot charge, when forced down the tiny bore, comes out as a long, patchy string

of pellets providing little margin for shooter error. It also has range limitations and most successful shooting

17

This chart shows the relative spreads of the three most

common hunting chokes in this country. Improved-

cylinder offers the greatest area of usable pattern at

some loss of long range efficiency.

is at considerably closer range than that of larger gauges. If one must shoot a .410 at doves, the best place to do it is either alone or at a .410-only dove shoot

where competition from larger gauges does not make a

tough proposition worse.

The 28 gauge is a more efficient shotgun than the .410. It is not often seen because its ammunition is relatively scarce and expensive. Also it throws a light shot charge and is a pretty tough gun to shoot well.

The 12-16-20 gauge class of guns are the meat and potatoes of most field shotgun shooting. Probably about 90 per cent of everything that is shot on the wing falls to one of these gauges. The reason is simple. These are the gauges which throw an ample amount of shot in a reasonably good pattern and with which most shooters can

score a reasonable percentage of hits.

The truth is that gauges do not kill doves nor anything

else. Neither does the height of brass at the shell's base.

What does kill flying game and break clay targets is the swarm of pellets flying in a loosely organized mass which intercepts the target's flight. The hard ballistic fact of life is that the more pellets in the denser mass

provides statistically better chances for a hit or multiple

hits. The multiple hit concept is most important on game, because while one pellet will break a clay target,

18

it usually takes several pellets to effect a clean kill on a game bird.

Doves are small birds, and they are relatively fragile. There is no need for heavy pellets, but there is a need for a dense cloud of small ones. Shot sizes IV2, 8, or 9 are perfectly adequate for all dove shooting.

Every shotgun charge fired has weak spots in its pattern. This is not too important when shooting at a goose

or a pheasant because the size of the target is usually larger than the holes in the pattern. (If your shotgun consistently throws patterns with open spaces a goose could fly through, you might consider trading it before dove season.)

Shotguns in the 12-16-20 gauge class are about right for most of us. The 12 is functionally superior because it throws more shot better than either of the smaller

gauges. The 16 is almost as good, but this gauge is losing popularity because it is sandwiched between the 12 and 20. As shotgun loadings have progressed and more

diversified load combinations are offered, there is less

A difference these days between the gauges. 12 gauge

with a light load or a 20 gauge with a heavy one covers the 16 gauge's traditional niche. If you have a 16 gauge

go ahead and shoot it; the doves don't know that it's not

a 12 or 20.

The 20 gauge is a fast comer these days because modern loadings take it right up to 12's backdoor. 20

Outdoors \t) Georgia

% gauge loadings from up to 1 Va ounces of shot can be

had, although one must go to magnum shells for the

heaviest loads. Still, though, the 20 is ballistically inferior to the 12 because the small bore "strings" the

shot. That is, the same amount of shot going down a smaller tube forms a longer column and out at 30 yards the column is longer still. This stretched out pattern is apt to have more thin spots for targets, or doves, to slip

through. Actually this difference, though real, is pretty mar-

ginal in practical field shooting and a good shot with a 20 will generally top a duffer with a 12. Which goes to show that any shotgun delivering from 1 to 1 Va ounces of IVi or 8 shot can reasonably be called a dove gun.

In 12 gauge shells commonly available the best shells are the 1 Vs or 1 Va ounce loadings. The so-called

"pigeon" loads of 3Va dr. equiv. of powder and Wa

ounces of IV2 or 8 shot are superb dove loads. The high brass or "high power" express shells are really not

Guns and equipment courtesy: Chuck's Firearms, Buckhead The Gunroom, Smyrna

The wise shotgunner will check out his favorite smoothbore vAth a variety of loads to find what combination gives the best efficiency.

Septerpber/October 1977

19

necessary and deliver more recoil for no significant gain

in effectiveness. The so called 1 ounce "dove" loads in

1 2 gauge sold at bargain prices are really not such bag-

gains. They reduce the 12 gauge to the 20 gauge class.

While the patterns are theoretically superior, one might

as well go and shoot a 20 for the snob appeal.

The 16 gauge shells are commonly available in 1 and

1 Vs ounce loadings. Go with 1 Vs ounce if possible.

% Twenty gauge field loads are available in

and 1

ounce loadings. The 2% inch magnum shells give 1 Vs

ounces and the 3 inch magnum delivers 1 Va . It is doubt-

ful that the magnum shells are worth the difference in

cost and recoil.

What choke to use is an extremely variable question;

perhaps the best answer is a variable choke. It seems

that there is an unwritten law in dove shooting which

provides that the doves always fly wrong for the choke

you are using on any given day. If by chance you have

an open choke the doves can be counted on to be leav-

ing vapor trails through the stratosphere. The next time

you show up with a full choke and the birds try to land

in the eight foot tall sumac bush you are using for shade

and a blind. Actually, on some exclusive shoots, one

could move to where the doves are moving at a gener-

ally reasonable altitude for the gun at hand. Moving

about the field is generally frowned on at the many

paid, semi-public shoots these days. You stay where you

draw or are assigned, period. In such instances a vari-

able choke device is really a plus, but if that extraneous

20

t

\

"'WP^V .c-i1-*-

(Top) The variable choke offers the most versatility in

chokes but is a bit ugly. (Bottom) This lineup shows the

-- A differing payloads of, from left: .410 3 oz.,

--% -- 29 ga.

oz., 12 ga. IVs oz.

blob of metal on the end of your gun barrel bothers you,

go with modified. This is probably the best all-around

choke for today's catch-as-catch-can dove shooting.

Taking the average of all this, the seemingly optimum

dove gun would be a gas operated autoloader in 12

gauge with a modified barrel. It would be loaded with

A pigeon loads of 3V4

dr.

equiv.

and

X

\

ounces of #8

shot. This combination would carry on from opening

day through the end of the season. It wouldn't be per-

fect for all situations but would perform reasonably

well in most.

^

Outdoors ip Georgia

Hunting in Georgia

It is a simple thing to ask someone how the

hunting in any state or region is, but generally it is not quite so simple to answer. Just to say

"It's good" or "It's bad" isn't much help, particularly since "good hunting" often carries

different meanings for different people. Basically, what most call "good hunting"

involves an abundance of game animals and enough room to safely enjoy the sport. Like most species, game animals annually produce a surplus of young to insure an adequate breeding stock for the next mating season. It is from this surplus that the hunter takes his harvest ; and on this abundance he must depend

for the quality of his sport.

So he is dependent on a variety of favorable natural conditions : an ample supply of food,

water, cover, and "elbow room" are some of

these. Animals are selective, and they will live and breed to abundance only in an environment which fills their needs. To further complicate things, different animals have different needs, so terrain which offers good hunting for one species is not necessarily productive

for another.

By this definition, Georgia has good hunting for most of the game species native to the

state, for there are plenty of the natural resources that produce an abundant supply for the state's hunters each year. These resources are diverse, so they produce an enviable variety

of game. On the whole, Georgia hunting is good. The question of elbow room often concerns

the sportsman who doesn't own land. Finding a

place to hunt can be a serious problem for

many Georgia hunters, but often this problem

can be solved merely by knowing where to

look for public land.

The largest blocks of public land in the state are the Chattahoochee and Oconee National Forests managed by the U.S. Forest Service. The 781,700 acres of forest land in these areas is open for public hunting according to state regulations. Nearly 300,000 acres of this

national forest land is included in the AVildlife

Management Area system of the Game and

Fish Division, Department of Natural Resources. There are more than 40 Wildlife Management

Areas under strict supervision by the Game

and Fish Division's biologists and conservation rangers. These areas are managed to produce good conditions for wildlife. The management area system includes more than 1.5 million acres of land which, because of the strict control, produces high quality hunting for the sportsman.

More public hunting is available on military posts, although civilians must get permission from the Post Provost Marshal.

By far the greatest portion of hunting land

in Georgia is owned by private timber

companies : over 3 million acres. Many of these

companies allow hunting on their land, and a few have instituted fee hunting on some areas, using the income to manage wildlife habitat on the lands.

Overall, the prospect for Georgia hunters is

encouraging, both now and in the future.

Edited by Aaron Pass Revised 1977 by Brenda Lauth

Septerpber/October 1977

21

Wildlife Management Areas

Georgia's Wildlife Management Area System is the average hunter's

best opportunity for good sport on public land. Including more than 1.5 million acres in 48 separate areas scattered over the state, this system provides an abundance of public hunting and other outdoor

recreation.

Most areas are supervised by a refuge manager who oversees management operations and enforces wildlife regulations. As a result of these efforts, the Wildlife Management Areas usually produce better

wildlife populations than the surrounding areas.

NORTH GEORGIA Allatoona WMA: 17,000 acres near

Cartersville. Deer, squirrel, quail,

rabbit, dove. Tommy Jenkins. Berry College WMA: 30,000 acres

near Rome. Deer, squirrel, rabbit, quail. Donnie Bagley.

Blue Ridge WMA: 42,000 acres near

Dahlonega. Deer, squirrel, grouse, raccoon and turkey (spring). H. C. Cruce and W. R.

Sutton.

Chattahoochee WMA: 23,000 acres

near Helen. Deer, squirrel, grouse, raccoon and turkey

(spring). A. C. Abernathy.

Chestatee WMA: 25,000 acres near

Turner's Corner. Deer squirrel, grouse, raccoon. Roosevelt Key.

Cohutta WMA: 95,000 acres near

Chatsworth. Deer, squirrel, grouse, raccoon and turkey (spring). J. G. Dover and Hugh

Greeson.

Coleman River WMA: 1 1,000 acres

near Clayton. Deer, squirrel, grouse, raccoon. Bruce Youngblood.

Cooper's Creek WMA: 34,000 acres

near Dahlonega. Deer, squirrel, grouse, raccoon. Eugene Burn-

ette.

Coosawattee WMA: 30,000 acres

near Ellijay. Deer, squirrel, rabbit, grouse, raccoon. Stanley

Harris.

Dawson Forest WMA: 10,000 acres

near Dawsonville. Deer, squirrel,

rabbit, quail, raccoon and some

grouse. William Thacker. Hart County PHA: 945 acres near

Hartwell. Deer, rabbit, quail, dove.

Johns Mountain WMA: 23,000 acres

near Calhoun. Deer, squirrel, raccoon, turkey (spring). Raiford

Russell.

Lake Burton WMA: 13,000 acres

near Clayton. Deer, squirrel, grouse, raccoon, turkey (spring). Allen Padgett.

Lake Russell WMA: 17,000 acres

near Cornelia. Deer, squirrel, rabbit, quail, raccoon. Harold Waycaster.

Little River WMA: 17,000 acres

near Canton. Deer, rabbit, quail, squirrel. Ted Touchstone.

Pigeon Mountain WMA: 17,500

acres near LaFayette. Deer, squirrel, rabbit, raccoon. Lawton Mas-

singill.

Rich Mountain WMA: 45,000 acres

near Ellijay. Deer, squirrel, grouse, raccoon. Randal Hensley.

Swallows Creek WMA: 1 9,000 acres

near Hiawassee. Deer, squirrel, grouse, raccoon. Fred Schuler.

Talking Rock WMA: 20,000 acres

near Jasper. Squirrel, rabbit,

quail, raccoon. Danny Dobson.

Warwoman WMA: 14,000 acres

near Clayton. Deer, squirrel, grouse, raccoon. George Speed.

MIDDLE GEORGIA

Baldwin State Forest: 2,500 acres near Milledgeville. Rabbit, quail, squirrel, dove.

Big Lazer Creek WMA: 2,700 acres

near Talbotton. Deer, squirrel, turkey (spring).

Carroll County PHA: 21,000 acres near Whitesburg. Deer, squirrel,

rabbit, quail.

Cedar Creek WMA: 30,000 acres

near Monticello. Deer, squirrel, rabbit, quail, dove. Joe Bilderback. Central Georgia Branch Station: 12,000 acres near Eatonton. Deer, squirrel, rabbit, quail, dove, turkey (spring). Jerry Crews.

Clark Hill WMA: 15,000 acres near

Thomson. Deer, squirrel, rabbit, quail, dove, turkey (spring). Ronnie Thomaston. Fishing Creek PHA: 2,400 acres near Washington. Deer, rabbit, quail, squirrel, dove, waterfowl.

Oaky Woods WMA: 28,000 acres

near Kathleen. Deer, quail, rabbit, squirrel, dove. Larry Ross.

Ocmulgee WMA: 36,000 acres near

Tarversville. Deer, squirrel, rabbit, quail, dove, turkey (spring).

Bob Watson.

Ogeechee WMA: 24,000 acres near

Warrenton. Deer, squirrel, rabbit, quail, dove, turkey (spring). Joe Smallwood.

Rum Creek WMA: 5,200 acres near

Forsyth. Deer, squirrel, rabbit,

quail.

West Point WMA: 6,200 acres near

LaGrange. Deer, squirrel, rabbit, quail, dove, waterfowl, turkey (spring). James Hackley.

SOUTH GEORGIA

Albany Nursery: 300 acres near Albany. Dove. Bill Wilson.

22

Outdoors in Georgia

Aitamaha Waterfowl Area: Near Darien. Waterfowl, snipe, rabbits, dove. Eugene Love.

Arabia Bay WMA: 45,000 acres

near Homerville. Deer, squirrel, rabbit, quail. Robert Kilby.

Brunswick Pulp & Paper Area:

60,000 acres near Jesup. Deer, squirrel, rabbit, fox, bobcat, raccoon. Ross Knowlton.

Bullard Creek WMA: 16,000 acres

near Hazlehurst. Deer, squirrel, rabbit, quail, turkey (spring). Wendell Deloach.

Chickasawhatchee WMA: 24,000

acres near Albany. Deer, squirrel, rabbit, quail, dove. Keith O'Mary.

Dixon Memorial Forest: 37,500 acres near Waycross. Deer, quail, rabbit, squirrel. Wallace King.

Grand Bay WMA: 9,000 acres near

Valdosta. Deer, squirrel, quail, rabbit, dove, waterfowl, raccoon, opossum. S. L. Strickland.

Hazzards Neck WMA: 12,000 acres

near Brunswick. Deer rabbit, quail, squirrel. David Edwards.

Horse Creek WMA: 16,000 acres

near Jacksonville. Deer, squirrel, rabbit, waterfowl. Herbert Adams. Lake Seminole PHA: 5,000 acres near Lake Seminole. Deer, squirrel, rabbit, quail, waterfowl.

Bobby Stubbs.

WMA: Little Satilla

15,000 acres

near Patterson. Deer, squirrel,

rabbit, quail. Ross Knowlton.

Muskogean WMA: 19,000 acres

near Jacksonville. Deer, squirrel,

quail, rabbit, waterfowl. Stephen

Belew.

Rayonier WMA: 19,000 acres near

Nahunta. Squirrel, rabbit, quail.

Ross Knowlton.

Sapelo Island WMA: Deer. C. V.

Waters.

Suwannoochee WMA: 23,000 acres

near Valdosta. Deer, squirrel,

quail, rabbit. Jim Coleman.

Tennessee

.-/ I--4-4I

\ f "''"'CMftaKooon

North Carolina

>**3

/ .?'"f^7V_ V fa*..*, (to"..

:

\

F ......

l

-

mjL

&f^ """ AllB^oona WMA rfttf Uttl Ri4 WMA

X/

f"

-ryt\- VO >\J

1,7

GEORGIA

Areas open to public I Managed land

v~-

V -~?t*^l m rf<y Jte^-r' \ vU r\

X _< >

--

-A ""'wMa!*?-' ButlardCraa>WMA

"^Jv '

r

L,

J

j ^i ' l ^"."^^^tSSn

~ J

ibardi)landN^Joni V^ildl.URwQt..

IK ^ i 1-rX iiekiJwhlch* WMA

j

T -- V -r\ --S*-*\:-r^ I

II

\\ \S^--

LmiwV.aM^I* WMA-fB WMA

f

^VVi-,

Vd

^ ""

-Hi

-- V -^""t

la

,

Bay

Memorial For.

WMA \ JCM

*

(

L -4""\ T

I Grand li|WIM -Bsuwtnnooch**

<3W; ^ ,i-,

. L,

,, , "~7

\

Florida

Septerpber/October 1977

23

INDUSTRIAL FOREST LAUDS

Finding hunting land is perhaps the major problem facing today's sportsman. Permission to hunt on private lands is difficult to obtain, but perhaps even more difficult is finding the owner of the land to ask permission.

Many of the forest industries in Georgia have vast

acreages which they allow hunters to use if permission is requested. In fact, more than three million acres of industry-owned lands are open by permission in Georgia each year.

As a public service, we provide this list of forest

industries to aid sportsmen in obtaining permission

to hunt. The list was compiled in cooperation with the Southern Forest Institute. Hunters are reminded to respect the owner's property and to abide by any company rules.

The Department of Natural Resources, in publishing this list, does not guarantee that hunting privileges will be granted by any company or on any land. The Department reminds hunters that they must have the permission of any landowner, including forest

industries, before hunting.

No information is available from the Department about the location of this land. Maps may be available

from some of the companies.

To request information and hunting privileges from the various companies, contact:

Armstrong Cork--S. L. Anderson, Manager, Woodlands Division, Armstrong Cork, P.O. Box 4288, Macon, Georgia 31208.

-- Brunswick Pulp Land Company George M. Ference, Forest

Administration Manager, Brunswick Pulp Land Company, P.O. Box 860, Brunswick, Georgia 31521. Container Corporation of America-- Paper Mill Division, North Eighth Street, Fernandina Beach, Florida 32034; also John Johnson, Area Forester, Container Corporation of America, Waycross Area Headquarters, Box 1884, Waycross, Georgia 31501; Walt Branyan, Area Forester, Container Corporation of America, McRae Area Headquarters, P.O. Box 237, McRae, Georgia 31055; Ed Pope, Area Forester, Container Corporation of America, Cussetta Area Headquarters, P.O. Box 58, Richland, Georgia 31825.

-- Continental Forest Industries lands leased by private hunting clubs

will be posted and are for members only; land open to the public is marked with white boundary bands and signs with "Continental Can." No prior approval necessary for open company land. If land is closed it will be well marked.

-- Georgia Kraft Company Woodlands Division, P.O. Box 1551, Rome,

Georgia 30161; also District Managers, P. H. Brewster, P.O. Box 103, Coosa, Georgia 30129; C. H. Everett, 500 Spring Street, Suite 205, Gainesville, Georgia 30501; J. H. Colson, 2031 Devenshire Drive, Columbus, Georgia 31904.

Gilman Paper Company-- St. Marys, Georgia 31558; J. G. Fendig, Manager, Timber Division, Gilman Paper Company, St. Marys Kraft

Division, St. Marys, Georgia 31558; Fred Crosby, Gilman Paper Company, St. Marys Kraft Division, St. Marys, Georgia 31558;

Charles Goodowns, Route 15, Box 150, Maxville, Florida 32265; Ray Gore, P.O. Drawer 548, Day, Florida 32013. Great Northern Paper Company--W. W. War, Timberlands Manager, P.O. Box 44, Cedar Springs, Georgia 31732. International Paper Company-- Bill Tomlinson, Wildlife Specialist, Woodlands Division, P.O. Box 518, Georgetown, South Carolina

29440. ITT Rayonier-- P.O. Box 528, Jesup, Georgia 31545; also, Thomas E.

Evans, Area Supervisor, ITT Rayonier, Inc., Eastman, Georgia 31023; Raymond Johnson, Area Supervisor, ITT Rayonier, Inc., Waycross, Georgia 31501; C. B. Smith, Area Supervisor, ITT Rayonier, Inc., Swainsboro, Georgia 30401; Danny House, Area Supervisor,

ITT Rayonier, Inc., Jesup, Georgia 31534.

Langdale Company--Gene Quick, Contract Administrator,

P.O. Box 1088, Valdosta, Georgia 31601.

-- Owens-Illinois Harry Bumgarner, Manager, Southern Woodlands,

Owens-Illinois, Inc., P.O. Box 1048, Valdosta, Georgia 31601.

St. Regis Paper Company--W. J. Robertson, Chattahoochee Forest,

P.O. Box 686, Lumpkin, Georgia 31815; J. C. Biggert, Flint Forest, P.O. Box 38, Warwick, Georgia 31796; E. N. Cooper, Suwannee District, P.O. Box 115, Fargo, Georgia 31631.

-- Union Camp Corporation George Gehrken, Woodlands Division,

P.O. Box 570, Savannah, Georgia 31402.

-- West Vaco Corporation John Wilson, District Forester, Route 3,

Box 26, Winnsboro, South Carolina 39180; A. W. Craig, Route 5, Box 395A, Union, South Carolina 29379.

24

Outdoors in Georgia

COMMERCIAL SHOOTING PRESERVES

The following1 list includes facilities which were verified in 1977 or were listed by the National Shooting Sports Foundation's 1976-77 directory of commercial shooting preserves. . It is not an endorsement of the services offered by any preserve.

The commercial preserve season runs from October 1 through March 31. For hunting on preserves only a special non-resident license may be purchased for

$5.25.

Commercial Shooting Preserve Notchaway Hunting Preserve 1-75 Hunting Preserve Marsh Hunting Preserve Ogeechee Lodge

Ashburn Hill Plantation Quailridge Shooting Preserve Warrior Creek Plantation Little River Farm Edgewood Kennels and Hunting Preserve

The Home Place

Callaway Gardens Hunting

Preserve

Address 205 W. Main Street

Colquitt, GA 31737

2501 Oak Street

Valdosta,GA 31601

Route 3

Statesboro, GA 30458

Route 4, Box 392

Savannah, GA 31405

P.O. Box 128

Moultrie, GA 31768

Box 155

Norman Park, GA 31771

Route 3

Moultrie, GA 31768

75 N. Mill Road

Atlanta, GA 30228

P.O. Box 81

Calhoun, GA 30701

Hill City Rural Station

Resaca, GA 30735

Pine Mountain, GA 31822

Marben Farm Hunting Preserve Attaway Farms Redbone Farms Hunting Preserve

Riverview Plantation Sowatchet Plantation

Mansfield, GA 30255

Route 3

Wrightsville, GA 31096

P.O. Box 354

Barnesville, GA 30204

Route 2, Box 225

Camilla, GA 31730

Box 609

Bostwick, GA 30623

Pulaski Hunting Preserve

Hudmar

Tallawahee Plantation Buddy Parrish and Sons

Wayne County Hunting Preserve

Route 3

Hawkinsville, GA 31036

P.O. Box 868

GA Reidsville,

30453

Route 5, Box 204

Dawson, GA31742

Box 38

Pavo, GA 31778

Route 1, Box 62

Jesup, GA 31 545

Contact Person/ Telephone

T. W. Rentz, M.D. (912)758-3313 Converse McKey (912)242-3764 Wendell Marsh (912)587-5727 Jack Douglas (912)925-4459

F. R. Pidcock (912)985-1507

Edwin Norman

(912)769-3201

Gene Reed no phone George Ivey, Jr. no phone Wayne Elsberry (404)629-8154 W. C. Floyd (404)629-7102

Dutch Martin (404)663-2281 Atlanta 688-8542

Columbus 324-2234

B. C. O'Boyle (404)786-3331 Robert Attaway, Jr. (912)864-2318 A. N. Moye, Sr. (404)358-1658 Cader Cox, III (912)294-4904 David Morris (404)342-1574 Atlanta 523-4680

Lonnie E. Slade (912)892-9623 David E. Hudson (912)557-6441 J. E. Bangs (912)995-2265

Buddy Parrish (912)859-2411 H. E. Ogden no phone

Game

Availcible

Quail

Quail

Quail Quail, Boar, Deer, Duck,

Dove

Quail

Quail Pheasant, Quail

Pheasant, Quail Pheasant, Quail

Quail

Pheasant, Quail

Quail Quail, Dove, Deer

Quail Quail, Duck Deer

Pheasant, Quail Pheasant, Quail

Quail

Quail

Quail

County

Location Baker Brooks Bulloch

Chatham

Colquitt Colquitt Colquitt Fulton

Gordon Gordon

Harris

Jasper Johnson

Lamar

Mitchell

Morgan

Pulaski Tattnall Terrell

Thomas Wayne

Septerpber/October 1977

25

GAME SPECIES

DEER

Slim and graceful, the whitetail

deer (Odocoileus virginianus) is the classic symbol of eastern hunting

and the most popular big game animal in the state. The fact that more

than 175,000 Georgia hunters seek this elusive quarry each year is one of the brightest success stories in wildlife conservation, for it points out the effectiveness of modern

game management techniques. The whitetail deer was virtually

extinct in Georgia and most of the Southeast at the turn of the cen-

tury. By the Civil War, most of the

state had been cleared for agriculture and except for the mountains and the river bottom swamps there was almost no deer habitat left even these refuges offered little protection from heavy hunting with no control or restriction.

Since World War II much for-

mer cropland has been "let out" to grow back to forest. This return to woodland was augmented by a whitetail deer restoration program and strict game law enforcement by

the Game and Fish Division. Today

deer are numerous in all but the

metropolitan counties of the state.

Much good deer range is open to

public hunting, although middle Georgia probably is the favorite

area.

There is plenty of good deer range open to the public. Deer hunters must secure permission before hunting on private land and should check current hunting regulations for seasons and firearms limitations.

SQUIRREL

The gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) and the larger fox squir-

rel (Sciurus niger) are the second

most popular game animals in Georgia. This popularity is due mainly to their statewide abundance and easy accessibility, which encour-

ages the hunter with limited time to seek squirrels. The gray squirrel

is the best known of the two since it is found all over the state. The

fox squirrel is limited to the pine

thickets and farmlands of Central and South Georgia.

The gray squirrel feeds on the fruits and buds of hardwoods and makes his home in hollow trees, so he is a resident of mature hardwood forests. The increase of hardwood

acreage over the state has been good for gray squirrels and the population is increasing. In fact, a special early season has been established in North Georgia to better harvest this abundance. The statewide season usually begins early in October and runs through February.

There are two major differences of opinion regarding squirrel hunting. One is whether to stalk or sit. The stalker moves quietly through the woods seeking his quarry, while the sitter stays put and lets his target come to him.

The second controversy involves the appropriate armament. There are riflemen who insist that the .22 rimfire is the classic choice and the

%AAA/WWVWWWWWWWWW^A*MAftrtA/WSArtMAfl^WWW

RABBIT

The eastern cottontail rabbit (Sylvilagus floridanus) is the main

character in that traditional local