Jimmy Carter

Governor

Joe D. Tanner

Commissioner Department of Natural Resources

George T. Bagby

Deputy Commissioner for Public Affairs

STATE GAME AND FISH COMMISSION

James Darby Chairman

Vidalia-1st District

William Z. Camp, Sec. Newnan-6th District

leo T. Barber, Jr. Moultrie-2nd District

Dr. Robert A. Collins, Jr. Americus-3rd District

George P. Dillard Decatur-4th District

Rankin M. Smith Atlanta-5th District

Leonard E. Foote Marietta-7th District

Wade H. Coleman Valdosta-8th District

Clyde Dixon Cleveland-9th District

Leonard Bassford Augusta-1Oth District

Jimmie Williamson Darien-Coastal District

------

EARTH AND WATER DIVISION Sam M. Pickering, Jr., Diredor

ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION DIVISION R. S. Howard, Jr., Director.

GAME AND FISH DIVISION Jock Crockford, Director

PARKS AND RECREATION DIVISION Henry D. Struble, Director

OFFICE OF PLANNING AND RESEARCH Chuck Parrish, Director

OFFICE OF ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICES James H. Pittman, Director

PUBLIC RELATIONS AND INFORMATION SECTION H. E. (Bud) Yon Orden, Chief

FEATURES

Beneficent Bobcats

GeorgiologyProvidence Canyons

Fungus Among Us

Log Cabin Bears

BackpackingBoots & Packs

T Craig Martin 2

Allen R. Coggins 7 T Craig Martin 12 Aaron Pass 14

T Craig Martin 18

DEPARTMENTS

Outdoor World

24

Sportsman's Calendar

25

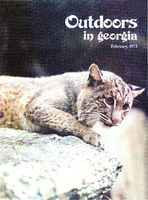

ON THE COVERS

ON THE FRONT COVER: The bobcat, native to Georgia, is much misunderstood and much maligned, but is in fact a beneficial predator. See " Beneficent Bobcats," by T. Craig Martin on page 2 of this issue. Photo by Jim Couch, with photo arrangement courtesy of Red Palmer.

ON THE BACK COVER : Fire and Ice. Top photo by Bob Busby. lower photo by T Craig Martin.

Outd()ors it? ge~rgia

February 1973

Volume II

Number 2

Outdoors in Georgia is the official monthly magazine of the Georgia Departm ent of Natural Reso urces, published at the Department' s offices, Trinity -Washington Building, 270 Washington St., Atlanta, Georgia 30334. No advertising accepte d. Subscriptions are $3 for one year or $6 for three years. Printed by Williams Printing Company, Atlanta , Ga. Notification of address change must include old address label from a recent magazine, new address and ZIP code, with 30 days notice. No subscription requests will be accepted w ithout ZIP code. Articl es and photographs may be reprinted when proper credit given. Contri bution s are wei. come, but the editors assume no responsibility or liability for loss or dam age of articles, photographs, or illustrations, Second-class postage paid at Atlanta, Go.

Staff Writers Dick Davis Aaron Pass

T Craig Martin

MAGAZINE STAFF Phone 656-3530

H. E. (Bud ) Van Orden Editor-in-Chief

Bob Wilson Editor

Art Director Liz Carmichael Jones

Staff Photographers Jim Couch Bob Busby

Linda Wayne Circulation Manager

EDITORIAL

What Better Time

We sit back complacent, and lazily repeat to ourselves, there's still plenty of time. Our only problem is that we begin to believe what we're saying instead of realizing that her~ we go again-procrastinating.

Yes, there is plenty of time left right now, but in a few short weeks, March the 21st to be exact, spring will be burstjng forth and 11 days later trout season opens and then it will be too late.

Soooo-what better time than now to prepare ourselves and our equipment for the upcoming seasons that will bring us closer to the out-of-doors.

You'll be doing yourself a big favor if you get out your camping equipment, boating and fishing gear, hiking boots-whatever, now, and make sure they're ready to go when you need them. It's a lot safer for you, your family and other outdoorsmen if your equipment is in good shape.

If you put any hunting equipment away that needed a little work, why not get it out and make sure it will be ready when you are next fall.

What better time than now

Beneficent Bobcats

By T. Craig Martin

Among the denizens of our carefully stuffed menagerie in the Outdoors in Georgia office, there stands a bobcat poised on a pine log, peering forward as if planning his stalk of some little morsel that, alas, never will succumb to his pounce. His teeth didn't survive the transition from forest to office, his new eyes lack the flash of gold and green the originals once had, and his claws are forever sheathed in paws that have lost their spring-steel speed. But he remains the most fascinating and exciting creature in the collection.

For even in this toothless and stolid state, our bobcat is unmistakably wild. Visitors usually pet the fox and coo over the raccoon, but they seem content merely to look at the cat, as if his ferocious independence has carried over from life to create an aura that protects him from human intrusion. While alive he respected and avoided man, and he would not be tamed; it seems somehow appropriate to respect him in death.

Few Georgians ever see a live bobcat, perhaps because those who do usually shoot at him, a response that would drive the most gregarious animal into solitude. This hostile greeting combines with the eat's solitary nature and more or less nocturnal habits to make him pretty much a stranger to most of us, although a few hunters specialize in stalking or calling cats and an oc-

2

casional deer hunter will catch a glimpse of one in the early morning.

Two subspecies of Lynx rufus, L.r. rufus and L.r. floridanus, live in Georgia, rufus in the mountains and floridanus in the coastal plain, but it takes a biologist to distinguish them. William Bartram's description of this "fierce and bold little animal" in his "Travels" would suit either: "They are not half the size of a common cur dog, are generally of a greyish colour, and somewhat tabbied; their sides bordering on the belly are varied with yellowish brown spots, and almost black waving streaks, and brindled."

He left out of this portrait, of course, the bobcat's most distinguishing characteristic: its strangely "bobbed" tail. This rather humorous appendage usually is about four to seven inches long, a comic addition to his two or three foot body. A cougar's tail, in contrast, is about half as long as his body, as is a house eat's. Although the tail markings are not crucial in separating Georgia's bobcat species, the black bar on the top of the bobcat's tail surely distinguishes it from its near relative, the Canada lynx, whose tail sports an all-black tip.

Bartram's colorful "not half the size of a common cur" suggests a confusing image. In fact, adult male bobcats weigh between 15 and 40 pounds, averaging about 20 to 25 in Georgia, while adult females range between 10 and 20

Phofo by leonard lee Rue II I

pounds. They are, then, larger than a cur terrier, smaller than a cur labrador. Domestic cats weigh somewhat less, seldom more than 15 pounds.

Bartram found bobcats "common enough" in the 1770s, which suggests civilization has done them no favors: recent estimates place the bobcat population at about 1.5 per square mile in the best modern habitat. They range throughout Georgia, but the Okefenokee Swamp and its National Wildlife Refuge probably harbors the largest single population. Some have claimed that the cats prefer "edge" or transition areas between swamp or river bottoms anp higher dry ground, but this preference may be more apparent than real. Certainly the rabbits and small rodents that live in such areas make the eat's hunting more convenient, but most evidence suggests that he'll live wherever he can find sufficient prey. Cats have been seen living quite happily in abandoned-but still rather openfields.

Like all non-human predators, the bobcat has been subject to some abuse because he lives by preying on other living creatures. His detractors portray him as living in rapine abandon, destroying hordes of some valuable species: the hunter invokes the image of the vicious cat pouncing on poor huddled Bambi, or, if his taste differs, describes the eat's insatiable appetite for tender young quail; the farmer imagines a bobcat in every henhouse, while the rancher screams for federal aid to protect his lambs or calves from the inevitable slaughter; and, finally, there is the grandmother's grandmother's friend whose baby was carried away by a foraging bobcat in '06.

Each of these myths, unfortunately, contains that infinitesimal grain of truth that allows men to cling to it long after rationality should have set in. The bobcat is, in fact, an opportunist; he'll eat anything he can catch and subdue, whether large or small, wild or domesticated.

If he can find an unprotected or weak fawn, he will kill it, but this happens infrequently in Georgia. W. T. Hewitt of Waycross, a dedicated bobcat hunter who works the edge of Okefenokee, says he's seen signs of bobcat attacking a deer only four times, and he's been hunting in that area for more than 25 years.

Bobcats certainly eat more quail than they do deer, but a careful analysis of bobcat feces in an area where quail were abundant showed that these birds made up only about 2.6 per cent of the cats' diet. And they eat more rabbits than quail, but the same study concluded that a good rabbit population could survive even heavy hunting by bobcats. Professional biologists in Georgia are unanimous: bobcat impact on game species is negligible.

There are infrequent reports of bobcats taking a chicken or two, and sometimes even a lamb. But Game and Fish Division biologists could report no instances of widespread predation on domestic stock in Georgia. Some western hunters of the federal Branch of Predator and Rodent Control have reported heavy attacks on stock, as have ranchers, but the professional consensus today seems to be that these reports are the result of overreaction to isolated incidents.

And that ancient old wife must have been telling tales: the authenticated accounts of unprovoked bobcat attacks on man invariably involve rabid animals. And even these instances can be counted on the claws of one paw. It is true that a bobcat will fight when cornered, as will any wild animal; and it is true that under these circumstances he amply earns his other name, wildcat. But if we respect valiant spirit in men and in domesticated animals, why not in wild creatures?

Unhappily for the mythmakers, the bobcat subsists on much less glamorous fare. He eats the most readily available prey, which, in Georgia, most often is the lowly cotton rat. He con-

~ 1 /1 1 /1 1 ~11111111111

~iii//MII I "'111/1l1l1l1l1l1l/1l1l~

III/IIIII

4

Pho tos by Jim Couch

Photo Arrangements Courtesy of

Red Pa lmer and Mac McWilliams, Palmer Chemicals

~~~~ li//l//111 //11)//1". il///1/111 1Hfill ,/I tl//lllll//11

11///ll/111

II/ li/////111

~~11/1/in ,,1)///111///". 11/1/1/PI ,/I tl/lllll//111 ~1//l/11111

5

sumes many rabbits as well, and a few birds, squirrels, snakes, and other small creatures that wander unwarily across his path.

In his realm, and against this sort of prey, the bobcat is a remarkably efficient predator, successfully completing nearly 40 per cent of his stalks. Dan Marshall, a Game and Fish Division biologist who studied the cats for his Master's Thesis at the University of Georgia, noted this success rate in the animals he observed, and contrasted it to that of wolves ( 8 per cent) and Indian tigers (8.3 per cent). Marshall noted that the only predator reported to be more efficient than the bobcat is the African wild dog, which downs 85 per cent of the game it chases.

Although he is a relatively efficient hunter, the bobcat still must work hard to survive. Marshall watched one cat sit out a thundershower, then creep through the lespedeza so slowly that it took more than 13 minutes to cover less than a yard to a cotton rat's nest. Its reward? One small rat, not a very satisfying feast for an animal that must consume about 500 times his body weight each year to live.

The bobcat's never-ending search for food does man more good than most of his human detractors are willing to admit. He, with the able assistance of foxes, hawks, and owls, keeps the rodent population within manageable bounds. And his tendency to prey on the weak and faltering protects game species from their diseased members. A rabbit with tularemia is more apt to be captured than a healthy one, as is a quail suffering from coccidiosis; either animal could transmit his illness to others of his kind and to man or his domestic stock if it does not fall to some predator. Constant predation also helps to improve game animals by insuring that weaker members of a species have less chance of reproducing before being killed.

Georgia's bobcats stalk their prey within fairly defined territories, although the females seem

,,,jj/1111

11111111111~

11/111111111

~' '" "'

6

'" ,,,,,,,Ill

~ ~'"'I'l ' ,,, ,

111/

/IIIII1!1

'

111/11111111

~'""""'

more territorial than the males. Marshall radiotracked several animals during his research, and found that while the males seemed to roam at will, the females maintained strict boundary lines against others of their sex. None of the animals ranged far, however: the most active male covered only about three miles in an average day. The females stayed within a home range of one to two square miles.

Both sexes seem to lead solitary lives after they mature, meeting briefly to mate and care for their young, then going their separate ways. The kittens are born about two months after conception ( 1 to 4 per litter), usually in the early summer. They change to a meat diet after another two months, and are on their own by fall. Hawks, owls, and foxes sometimes prey on young bobcats, but the mature animal has few enemies in Georgia.

Except man. Few men actually hunt bobcats, but it seems that anyone with a gun who sees one feels obliged to kill it. Those few who do hunt the cats must work hard these days. As Hewitt puts it, "Most of them would rather hunt foxes, because they're easier to catch. A bobcat will lose any dog trained to hunt fox after a couple of dodges, and only a few of us still train dogs to chase the cats." A very few hunters call the cats using an artificial call, but this technique is most successful at night, and has become less popular as stiff laws against jacklighting deer are enforced.

To die at the hands of a skilled and dedicated hunter is, perhaps, a fitting end for a bobcat. To succumb to a casual shot from a loafing deer hunter or casual target plinker is not. The bobcat deserves man's respect and concern, not his enmity; for it is only right that one efficient predator should appreciate another.

Perhaps it is something of this appreciation that moves our office visitors to gaze with quiet admiration at the stolid remains of a once beautiful hunter.

t\l\\\\11111

1I11~\\\1111 11\\l\\\\111 \\11!\11\ 11\\1\\UI tl\1\\\1111

''11111111

1

,;;1' /1/11:: ' 1111/1/1111

11

"1111/l/1111

,,11111/111

- - --------- - - - ---------

Georgiology

By Al len R. Coggins

Providence Canyons

It's no t the G rand Canyon, even if it ha s been called that by loca l people for many years, but it is impressive-this network of mamm o th gullies ca lled the Prov idence Canyo ns.

The formation of these 3,000 acres of canyons near Lumpkin, Georgia, occ urred ove r a very short period , geologica ll y speaking, a process which comm enced just after th e first se ttlers mo ved into the area and began pursuing the age-old practice of unrestricted farming.

Millions of yea rs ago, when the shore of the Atlantic Ocean abutted the present fall line, sediments from

the eroding Piedmont highlands washed down into the shallow sea covering this area to form the present day sands and clays. As the harder crust of surface soil where the canyons now lie began to break up in modern times, the lower, softer sediments gave little resistance to the forces of wind, water and gravity which gouged out the Providence Canyons. Even today central Georgia gully-washers continue their process of freeing grains of sand and sending them on their way to their resting place-the sea.

The people who really know the canyons, like Mr. Robert Baxter, Superintendent of the new Providence Canyon State Park, can testify to the fact that these giant gulches show different personalities each time one walks through them. Water flows over the clay-like gray floor of the canyons, sometimes in thin sheets, sometimes in mild-mannered streams. At times a stream will meander sideways across the entire width of a canyon floor in less than a day. This leaves bars and deltas to mark the path of previous flows.

Erosion occasionally loosens the earth which entombs ancient sea critters that lived and died here when marine life dwelt in central Georgia.

Scenic Providence Canyon State Park is located 40 miles south of Columbus, in Stewart County. It's eight miles west of Lumpkin, on State Route 39 connector from Highway 27. The park contains 15 separate finger-like canyons within 1,078 acres of pine and mixed hardwood forests. The largest gorge is about one-half mile long, and some of the canyons are 200 feet or more deep and perhaps 400 feet wide. Narrow columns of more resistant sandstone rise 50 feet in places, adding to the awsomeness of the scene.

The canyons are named for the ante - bellum Providence Methodist Church which still stands near the encroaching edge of a gorge. The church was built on solid ground in 1860, but erosion of the canyons

caused concerned parishioners to order it moved to its present location shortly after the Civil War. The ground where the church once stood is nonexistant today. In its place is a great abyss.

Church members face a similar problem today as the gorge continues to eat away the ground churchward. The church and its quaint little cemetery, containing several Civil War dead, will need to be moved again within a few years unless this erosion can be arrested.

There are several local legends concerning the formation of the Providence Canyons. Mr. George Lowe, a one-time resident of the community, theorizes that the canyons were started by water dripping from his grandfather's barn. Others say that a spring called Peed Spring (named for early landowner Henry Peed) started the erosion process. These theories could have some truth to them, but they do not offer the entire answer. The most widely accepted theory suggests that well established animal and Indian trails as well as roads once crossed the land which now contains the canyons. Water draining from cultivated fields, barn roofs, or whatever, probably followed these paths, eating away at the upper, more resistant soil and finally breaking through to the softer more erodable earth beneath. If this did happen,

and it seems quite feasible, the water could well have gouged out large gullies which, over a period of 150 years, could result in the present canyons. The poor farming practices of the past allowed large volumes of water to flow unchecked over easily erodable soil, thus forming a classic example of man-induced erosion.

The geology of the area is quite interesting and impressive. One can clearly see three vertical divisions of soil along the edge of the canyons. The uppermost division is called the Clayton Formation. This reddish layer averages 15 feet but can be as much as 25 feet thick. Its consolidated clay

8

and sand is much more resistant to erosion than the underlying layer.

Once this surface is broken, the easily eroded Providence Canyon sands of the middle layer are exposed to the clements and erosion proceeds quite rapidly This second 125-foot thick layer is composed of gray-white sands. The sands of the Providence Formation were being laid down during the time when the great dinosaurs reached their peak and began their long road to extinction .

The floor of the canyon is composed of a gray clay-like layer called the Ripley Formation. This formation is very resistant to water's wear and

because of this the canyons will not erode any further

Present day erosion is greatest upstream toward the head of the canyons, but lateral landslides of from 25 to 35 tons are not unusual. These slides occasionally carry large trees crashing to the canyon floor.

The canyon's colors boast a rain bow ranging from whites to reds, browns , blues, oranges and purples. Chunks of clay sometimes fall into the canyon and roll along a stream bed to form the clay balls often discovered there.

Cl imbing out of the gorges one uotices changes in vegetation that

generally correspond to differences in available soil moisture: swamp, white and chestnut oak, tulip poplars, sweetgum and willows thrive in the wet, sometimes flooded, soils along the floor of the canyons, while black, southern red and post oak, dogwood and persimmon are not as water loving and occupy intermediate slopes. Still higher, sassafras, sourwood, pines and blackjack oak occupy even drier soils.

Festoons of kudzu vine hang over the rims of the canyons in several places. Kudzu was introduced there to retard erosion several years ago because this hardy plant, a member

10

of the pe a famil y, is a rapid spreader with very broad leaves which check the impact of falling rain drops. Water thus is all owed to soak slowly into the so il rat he r tha n rapid ly runnine. off a nd causin g erosio n.

Partrid gebe rry, grasses and other low-growing herbs add a touch of gree n to the oth erwise barren grey of the canyon floor.

The rare Plumlcaf Azalea (Rhododend ron prunifolium ) is abund ant in the lowe r reache s of the canyons, al th ough thi s plant is fo und wild only in a twe lve-county area of south weste rn G eorgia and sou theastern A labama. Th ese azal eas put o ut th eir ye ll ow and o ran ge to deep sca rlet blossoms from late July to September. Ma ny people visit the canyons during

thi s time just to see this magnifi cent nora! d isplay

T he peo ple of Lum pkin and Stewart Co unty fo r ma ny yea rs car ried o n a cru sade to have th is area developed as a pa rk. As fa r back as 193 8, National Park offi cia ls visited the canyon s to in vestiga te this poss ibi lity ; b ut the aftermath of depression a nd th e o nslought of World W ar II curtailed any efforts in this d ir ectio n. None theless, th e pe rsistent cit izens con tin ued their effo rts . A re solution, in trod uced by State Senator H ug h C arter o n be half o f the people of th e 14th District in 1970, called for purch ase of the Provid ence Can yo ns site <~nd es tab lishment of a state park . Jn July, 19 71 , the citize ns ' dream fin ally began to be fu lfilled as Providence

Canyo n State P ark became a reality Sho rtly there after th e property was

purch ased and a planning fi rm was engaged to prepa re a comprehensive mas ter plan for th e pa rk . Purchases v:c re made with funds allocated by the State of G eorgia, Stewart Count y a nd the Fed eral Bureau of O utdoor R ec reat ion , but had it not bee n fo r the additio na l fin ancial assist ance of the people of Stewa rt Co unty, the park m igh t still be b ut a dre am . The ca nyons within this pa rk may someclay prove to be one of Georgia 's major to urist attractions , but, mo re import a nt, this park will preserve a Georgia site of nation al importance. Nowhere else in the southeast has such short term erosion left a more spectacular sight.

I l

Wherever we turn, there is a fungus among us. They create our bread, cheese and wine, masquerade as the delectable mushrooms in our haute cuisine, initiate the process that leads to some of our most importa nt medicines , and, finally , transmute death into a basis for renewed life in our forests, dumps, and trashbins.

If fungi - in the fo rm of blight or rust -

occasion ally destroy our crops, they always produce the nutrients that allow those crops to grow. This is, in fact, their most important service, for they dissect dead matter into its original mineral s, releasing these into the soil to be consumed by new plants.

In the process, they provide room for these new bein gs . Imagine a wo rld in which every tree Jay forever where it fell, every animal rem ained w.here it died, or each bit of trash stayed where it dropped - soon there would be no space for an ything new, and the dead would reign supreme. The fun gi save us from this imagin ary world by decompos ing the dead into their constituent parts and spreading them through the soil.

We see this process at work every time we walk in the woods. Those moldy leaves, that rotting log or stump, and that decaying rabbit all point to fungi busily transforming death into the bas is of life.

And we see parts of the fungi themselves, although usua11 y only the fl ower or reproductive organ , like those shown on these pages. The true body of the fungus (some scientists are reluctant to call it a plant) consists of microscopic threads, the hyphae, whi ch join in a tangled mass, the m ycelium; bu t th ese portions almost always are bidden fro m surface view.

The fun gi shown here are saprophytes, that is, they live on dead matte r. Others are parasites, preying on the living, while still others are parasites when they can find a live host, saprophytes when they canno t.

These particul ar fungi, brown and black members of the polyporaceae and the greenish members of the hydnaceae, grew on the same fallen log. They inhabited separate areas because each emits an enzyme that is hostile to competing species; but together they created marvelous designs on this old log near the Chattahoochee Ri ver in Habersham County.

Photos by the Author

12

13

(_)

0

....J

By Aaron Pass

Many hikers, backwoods campers and other assorted explorers have been mystified this past summer by finding small log cabins in some of the more remote areas of the north Georgia mountains. The small structures appear recently built and are so low as to prohibit standing up while inside. The guesses made so far have included trail shelters, equipment sheds, or simulated bunkers for the Army Rangers to wage mock war against. In truth, the structures are bear traps, set by wildlife biologists of the Game and Fish Division.

Most people thinking of bear traps envision massive contrivances. Large and cumbersome,

these traditional bear traps often required two men to "set" and would securely hold the biggest bear by one leg. The traps used by the Game and Fish biologist not only had to hold the bears, but be harmless at the same time.

The log-cabin traps, as well as the smaller culvert design, operate on the principal of overly large rabbit boxes. The animal enters the trap after bait, trips a release and the door slams shut. The animal is then securely but harmlessly held for later study.

Study is what the bear traps are all about. The traps are being set in conjunction with a proposed study of the north Georgia black bear,

14

and they themselves are part of a pilot study on, among other things, how to trap bears.

The habitat of the black bear ( Ursus Americanus) has for the past 70 years been shrinking before an expanding human population. For a good many years, the sighting of a bear has been a rarity More recently, bear sightings have become more frequent, and even common in some areas. This apparent increase in the number of bears in north Georgia has prompted the interest of the Game and Fish Division of the Department of Natural Resources.

Game and Fish is now in the process of initiating a full-scale study of the black bear in Georgia. Wildlife biologist Bob Ernst, the project leader, explains it this way, "If black bear is present in north Georgia in significant numbers, it is a valuable natural resource, which we should protect. In this study we hope to learn the density of our bear population, what are the preferred bear habitats, and by what measures we can best maintain these."

The study is expected to run for at least three years. It will consist of a trapping and tagging operation on three wildlife management areas and will include the use of radio telemetry to monitor bear movements. From this it is hoped that a viable population index will be established showing the density of Georgia's northern bear population. The habitat needs of the black bear will also be studied to identify food habits, denning sites, and other areas which the bears might

use. According to Ernst, "Black bears must be viewed as a limited and hence highly valuable members of the north Georgia wildlife community Should it become necessary to identify and specially protect prime bear habitat, we must know exactly what constitutes that habitat."

The work done this past summer and fall was part of a preliminary study which must precede the full scale project. This is due in part to regulations covering federal aid to states in wildlife restoration. Federal funds authorized under the Pittman-Robertson Act of 1938 are available to state conservation agencies for approved wildlife management projects. The money comes from an 11 % excise tax on sporting arms and ammunition. The state wildlife agencies are funded by the sale of hunting and fishing licenses, so in effect, it is the hunter and the shooter who pays for most wildlife work.

The pilot bear study completed this year established two prime considerations for state and federal cooperation on the comprehensive study, "Ecology of the Black Bear in the North Georgia Mountains." First, it established that there are a significant number of bears in the area and secondly, that there are reliable and effective techniques for studying a wild bear population.

The pilot study was, in effect, an experiment in the techniques of investigation. Titled "An Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Bio-Teleme-

Wildlife biologist Bob Ernst with a very groggy bear. This large male, weighing 366 pounds, was the largest trapped all summer, and had to be dragged from the trap by a truck.

15

Bear # 102, a 155 lb. male, was the first bear trapped and equipped

with a radio trackin g transmitter. This allowed an accurate tracing of his movements durin g the summer

Wildlife management personnel involved in th e bear study this summer (L-R) Willis

Foster, Biologic Aide; David Carlock, Wildlife Biologist; A. C. Abernathy,

R efuge Manager; and Bob Ernst, project leader, kneeling in foreground.

try as a Technique of Monitoring the Movements and Home Range Occupation of the North Georgia Black Bear," the study sought the best methods for accomplishing the desired results in the forthcoming comprehensive "ecology" study This summer's work centered around the trapping and monitoring techniques.

How, when, and where to trap was part of the study, as was a determination of the best type of trap to use. Three types of traps were evaluated, the log cabin type, the culvert, and the leg snare. The snare has been used with some success in other states, but was a poor producer here. The culvert trap is made from sections of 3-foot diameter steel culvert transported on a boat trailer It is moveable, cheap, and operates on the sliding door principle like a rabbit box. The log cabin trap was the most successful, but is also the most difficult to build and is permanent.

The techniques of radio telemetry were also investigated. One problem that arose was "bounce" of the radio signals in the mountain terrain . This was effectively dealt with as were the questions of how to handle and mark the trapped bears. Over the summer, 8 different bears were trapped and four others escaped the traps. One bear evidently enjoyed the proceedings so much that he was trapped twice more.

According to Ernst, the pilot project was successful , "We wanted experience and knowhow, and got both. The successful results of this study should influence the approval and the success of the comprehensive 'ecology' study next year"

Public assistance will be necessary for the coming study to be successful. Judging from the increasing number of sightings, the north Georgia bear population is on an apparent upswing. After the long scarcity many people don't know how to react to the black bear as a neighbor Since many rely on folklore and tall tales, there is an almost predictable panic reaction when a bear is sighted near a settled area. People shut themselves up and are afraid of the "savage beast." A local posse is formed and

16

with packs of dogs, they ritually hunt down and exterminate a "killer" bear

It looks great in the newspaper and, like little boys, the posse members congratulate each other on their bravery Actually, the black bear is not such an offensive beast. He much prefers

to go his own way and be left alone. On the other hand, the black bear is a relatively large and powerful animal and can be dangerous when treated carelessly or cornered.

For this reason , the study areas where traps are set are posted with warning signs asking the public to stay out. For one thing, human activity might cause the bears to leave and render the effort of building or setting the trap wasted. Of more paramount and direct importance is the possible danger to unwary passersby If, for example, a young cub were trapped , the mother would not abandon it. The protective instinct a sow feels for her young is very powerful and she will linger near the trap that holds her cub. In these circumstances, the sow must be considered very dangerous indeed. Ernst says that he and other project workers are particularly careful when they first approach a trap for this reason.

Biologist Ernst is very enthusiastic about the project and its early results. "Our ground for study is very fertile; Georgia has previously done very little in regard to bears, and not much has been done in the whole southeast."

Contrary to some erroneous local reports, the Game and Fish Division has not and will not stock any bears in the mountains. Ernst said, "We are dealing with a pure wild bear population in a wild habitat. These are not 'garbage can bears' like the ones in the Smokies. We originally thought the north Georgia bear population was very small, but our pilot study has indicated more than was expected. Hopefully the results of the forthcoming study of the black bear's ecology will tell us."

Did anyone get the number of that truck? In order to safely examine th e trapped bears, th ey had to be drugged with a

tranquilizer Sernylan was used and was reported to be extremely satisfactory as it

does not wear off abruptly . The bea rs apparently liked it as well and #102 got

himself trapped three times.

17

By T. Craig Martin 18

Blistered feet and an aching back can spoil the pleasure of a day on the trail, but the suffering often is unnecessary and usually can be avoided. Proper boots, carefully fitted, and a cautiously chosen pack will insure a comfortable evening whether the day's load involved only a good lunch or enough gear for a week on the trail.

Choosing the "right" boots is at least as individual a decision as selecting the "right" deer gun or worm rod: there are a few guidelines, but within these guidelines the range is wide and outside advice only slightly helpful. Just as a .460 Weatherby Magnum is inappropriate for whitetails, so a 5 Y2 -pound mountaineering boot is the wrong choice for Georgia trails. On the other hand, a fleaweight spinning rod won't pull that 9-inch worm through the brush at Lake George, and tennis shoes won't support feet burdened by a 40-pound pack. Once these outside limits are set, however, experience and prejudice take over as deciding factors.

For short walks with light loadsa scouting trip in deer country or one-

day hike up to that favorite trout stream, for example - almost any sturdy shoe will do, particularly if the walker is blessed with tough feet. An etched or lugged sole will help provide sure footing, and sturdy leathoc will add some support, but this type of walking is not so far removed from daily routine that it calls for protective measures.

Anything much beyond that, however, deserves more attention. Gear for an overnight or weekend trip can weigh as much as 20 or 25 pounds, and most feet can't cope with this extra load without some help-help in the form of good boots and some prior conditioning.

Some general considerations: Georgia trails, while often steep and sometimes muddy and slick, seldom are rocky, so they do not call for extremely thick soles and heavy scuff-resistant uppers; Georgia's weather is moderate, and won't necessitate extra liners or many pairs of socks; and finally, the 1954 U.S. Mount Everest expedition concluded that it took as much energy to move one pound on

the feet as to move five pounds on the back ... Which suggests a simple rule: don't buy more boot than you need.

Most backpackers prefer a rather low-cut hiking boot with a wafflepatterned Vibram (composition material) sole. Until recently, almost all these boots were imported from Europe and were fairly expensive, besides being molded on European lasts (a wooden model of the foot, around which the boot is formed), which differs from the typical American shape. But now that many American manufacturers are producing hiking boots, the price for a good pair has dropped to $20 or $25. The foreign boots cost $10 to $15 more, although a little searching may tum up a pair in the $20 range.

About six inches high, these boots weigh from two to seven pounds. The middle range - three to four pounds - certainly is sufficient for most Georgia hiking. Serious hikers look down on hunting boots and other high-top styles, but this probably is a hangover from the days when back-

19

packing was an esoteric sport. The only real arguments against high boots are that they're too heavy and th at they constrict the muscles of the calf. Sorr:e models may have too many exposed seams for really ro ugh work, but this is true of some pure hiker styles as well.

Seams, in fact, traditionally have been the key to quality in hiking boots the fewer exposed seams, the better the shoe. As in most things, cost is only a ge neral ind icator, and a fairly inaccurate one at th at; but well-made trail boots could always be identified by their lack of out side seams. Th is old stand ard rea lly isn't crucial on Georgia trails, where there are few sharp rocks to gouge and tear exposed joints and th read , although it still is a good indication of the amount of care th at went into the boot's design. And fewer outside seams make the boot easier to waterproof.

Some people fee l th at smoo th outer leather also is necessa ry for a real ly top rate boot, but this seems more of an ind ividua l preference than objective criterion. Rough-out (suede-like ) uppers resist scuffi ing much better, and seem to take waterproofi ng just as well.

But all this has to do with whether or not the boot will last, and that doesn't make very much difference if it doesn't fi t well . there's no sense being stuck with a pair of long-lasting blister factories.

T he best way to get a good fit, of course, is to find an honest and experienced salesman and put yourself at his mercy Since backpacking is fairly new in Georgia, however, knowing a little about the process may save a lot of grief. The boots should be snug in the heel and instep, loose around the toes. There should be 1/ 8-inch or less play in the heel when they're tightly laced, and your toes should never touch the front of the boot. If yo u're shoppin g in a store, always wear the socks you intend to hike in, if ordering by mail , wear them when you make the tracing of your foot. Don't pay much attention to size, for th ere doesn't see m to be much standardiza tion among va rious model s.

In the store, stand up in the boot with the laces loose and slide your foot fo rward to th e toe. If there 's about 1/2 -inch space at the back (about a finger's width) , you'll probably have enough toe room once the boots are properly laced. That is, laced loosely over the toes, but snug-

Th e large and smn/1 of hiking boots: on th e left is a conventional high top hunting boot, in the center a heavy m ountain eering

boot, and on th e right a light trail boot. (Ph oto arrangements courtesy of Nacoochee S tation Sports Shop, Sautee-Na coochee, Georgia.)

ly over the instep and the vertical portion of the shoe. When they're laced, have the salesman hold one boot tigh tly, then try to twist your foot; neither your heel nor the ball of your foot should move noticeably Then walk around some, up and down stairs, trying to force your toe forwa rd . If there's much play, those are the wrong boots for you. Be sure that there's at least Y2 -inch between the laces when they're tight at the shop ; if not, you may not be able to tighten the boots when the leather softens and conforms to your foot. And don't be afraid to show indecision . those boots are a major investment and should last you a long time, so it's wi se to be careful.

Once the boots are selected, they should be worn around the house for several days, then, if they still seem right, waterproofed before they're worn outdoors. Sno-Seal probably is the best ointment around, but it seems to stiffen the leather. Use it (especially around the seams) when rough conditions are expected, but Huberd's Shoe Oil is adequate for normal use. Both will tend to mat a rough-out fini sh, but that's better than soaking it with water.

Wear the boots as much as possible before trying any long trips. The lea1her must begin to conform to your feet, and your feet must toughen up a little before any great strain is put on them. Blisters are the inevitable result of skipping this conditioning, no matter how good the boots or careful the fit.

An aching back and sore shoulders can be at least as annoying as blistered feet, but they can be prevented. It's just a matter of having the right pack for the right load.

Packs come in nearly as many varieties as boots, but they can be divided into two general classes: those with frames, and those without. Those without, commonly called rucksacks, are the older form, and still are more popular in Europe, while the newer aluminum-framed models are the favorites here. Each type has its uses, although the skilled outdoorsman can make do with either style.

The common canvas Boy Scout pack looks much like the traditional rucksack, although the European models are somewhat more sophisticated. Essentially, it's just a bag fitted with shoulder straps and, sometimes,

20

A variety of hiking boots poised on the Chattahooch ee River. The left, center, and right models probably are too heavy for Georgia trails, while th e oth er two might not hold up well in rough m ountain work.

a waistband. The weight hangs from the shoulders in a fairly compact mass. Many -are narrow or teardrop shaped , which is ideal for hunters or rock climbers because there are no projections to catch on limbs or overhangs. Most have a single main compartment, wrth one or more outer pockets for easy access. They're made of canvas or nylon , are generally water repellent if not waterproof, and have reinforced bottoms to cope with the inevitable scuffing. A few models have flexible braces to cushion the back, and others have a modified frame that can help support the load . Rucksacks are relatively cheap, from $ 10 to $35, and are a good choice for sho rt trips and light loads. The day packs are ideal for carrying lunch,

extra clothes, ammunition, or fishing tackle comfortably and out of the way, and they cost only $15 or $20.

For long distances and heavy loads, however, nothing tops a packframe and bag combination. Unlike the rucksack, which drapes the load from the shoulders and concentrates the weight on the spine, the pack frame (with its vital waistband) puts the load on the hips and thigh s, where humans were meant to carry it.

These frames , usually welded aluminum or aluminum alloy, are contoured to fit the back and waist, although they never should touch either. A more or less elaborate system of padded shoulder straps keeps the fr ame centered, while a pair of broad nylo n bands (or, in some cases, nylon

mesh) at the shoulder blades and hips holds the frame slightly away from the body The really crucial facet of the rig, however, is the waistband , which , when tightened, supports the load and places it on the hips and legs . It does n't seem to matter much whether thi s is a full band that goes completely around the waist, or two straps connected to the frame that buckle in the front . If the frame is properly fitted , either style will provide the neces~a ry support.

This fitting should be done by someone who knows his business. The fr ame should ride fairly high , with the hipbelt circling the waist just above the flair of the hi.ps and buttccks. The backhands, which provide room for air circulation and prevent th e frame from chafing, should cross the back at the shoulder blades and

21

PIN TO HOLD

BAG

---------------

CONTOURED FRAME

PADDED SHOULDER

STRAPS

BACKBANDS - - - - - - - - - -- --

WAISTBAND

22

at the waist. None of the weight should be suspended from the shoulders have a friend hang on the frame ; if you feel any of the weight on the shoulder straps, something is wrong. Frames come in several sizes, and there's no shame in settling for something less th an "large" follow the manufacturer's advice and pick the one that matches your height.

Then there's the problem of finding a bag to put on this perfectly fitted frame. They come in several styles that can be differentiated only by personal prejudice. The main divisio ns are % -length versus full length , and single compartment versus multiple compartment. A 1-length bag is designed to leave room at the bottom or top of the frame for a sleeping bag, which is held on by a set of straps. The full length bag extends the length of the frame and requires that the sleeping bag be stuffed in. The single compartment sack is just that, a big empty sack that can be filled in a variety of ways . It provides the most usable space, and, in a full length model, room for more weight than anyone in his right mind would carry

The multiple-compartment sacks

Th e large and sma ll of packs: from left to right th ere is a day pack, a conventional ru cksack , and a fram e pack and bag with sleeping bag strapped undern eath .

A full y rigged 3/4- /ength pack and its frame. This t11 in-compartment bag /e((les room for the sleeping bag undern eath. Notice th e handy outside pockets.

23

usually have two sections, although some have three and even four. One is a large compartment that opens at the top, the other a slightly smaller area accessible through a zipper at the back. This arrangement requires a good deal less planning than the single compartment bag, for the gear is more readily available. Both types have several outside pockets for small items that must be kept handy.

For general use, the % length, twin-compartment, bag probably is a good starting point. It will serve most purpooes, and requires less experience for convenient use. It should be made of waterproof material, u sua11 y a coated nylon, although one of the very best manufacturers, Kelty Pack, Inc., makes only a water repellent bag (they do, however, offer a 4 oz. waterproof cover for the pack, a necessary addition). "Water repellent" is fine if it doesn't rain, but it's sure to mean wet gear if you're caught in a storm.

A good frame and bag is going to cost between $25 and $60, so it might be well to rent them for a while to see if you're really interested in backpacking before making the investment.

It is very easy to carry heavy loads on a packframe, but some care in arranging the weight will help. The heaviest gear should be packed clooe to the back and fairly high. This puts the weight near your center of gravity, and keeps the pack from pulling away from you. Most people seem to find the load easier to carry if it rides up around the shoulders, which is why the % length pack has room underneath for the light sleeping bag. But this high load is a little unstable, so ski-tourers and climbers often shift the bag down on the frame. A variation on this-also a standard safety precaution when crossing streams is to release the hipbelt when in precarious footing.

The packframe is quite unweildy in deme cover, and probably isn't a good choice for hunting. But there's no better way to carry gear into a camp.

Top quality boots and pack will be quite an investment, both in cost and in the time spent in making a good choice, but a few comfortable evenings in camp will make this payment seem eminently worthwhile.

the

OUTDOOR WORLD

PLANTING QUAIL FOOD

One of the methods of improving quail habitat is the planting of food patches. These patches should be laid out in strips or in irregular shapes and cover Ys to Y<l acre for each 2025 acres of habitat. These plants may be used as borders to woodlands and fields or on firebreaks when used in

conjunction with prescribed burning. Quail are mainly seed-eaters and a large number of plants are attractive to them. The table below is taken from Circular 578 of the Cooperative Extension Service, University of Georgia College of AgriCulture and lists some of the important quail foods used for plantings in this region.

-Aaron Pass

1. Kobe or Korean Lespedeza

Broadcast 30 to 35 pounds per acre from February 1 to March 1. Plant in clay, loamy or moist soils of medium fertility.

2. Hairy Vetch

Broadcast 20 to 30 pounds of inoculated seed per acre from September 1 to October 15. Pla.nJt in well drained soils.

3. Cowpeas

Broadcast 10 to 15 pounds per acre from May 1

(Tory, Iron, Clay, to June. Not productive on deep sandy soils.

Covington or Thorsby

Cream)

4. Cowpeas and Soybeans

Broadcast 15 pounds cowpeas and 15 pounds soybeans (Gatan or Laredo, other local soybeans) per acre on moderate to well drained soils of medium to good fertility.

5. Grain Sorghum (DeKalb E57, F64, Northrup King 222)

Broadcast 30 pounds per acre or plant in rows at 10 pounds per acre on moderate to well drained soils of medium to good fertility.

6. Brown-top Millet

Plant 20 pounds per acre drilled on sites as required by grain sorghum. Plant as late as possible to insure seed maturing before frost.

7. Bicolor Lespedeza* (seedlings)

Set 18 inches apart in three-foot rows, 200 to 400 feet long; four -to eight rows per plot. Pla.nJt from December 1 to March 1. Does well on all areas except deep sands or poorly drained soils.

8. Florida Beggarweed "tickclover"

Plant 10 pounds scarified seed per acre when com is "laid by" or not later than June 1. Plant only in South Georgia.

9. Benne "Sesame"

Plant five pounds per acre in rows around July. Best suited to South Georgia. Do not plant on same plot of land two or more years in succession due to wilt.

*Bicolor or other shrub lespedezas also make good cover plantings.

24

LOCAL TU CHAPTER GETS NATIONAL AWARD

In recognition of outstanding ef-

forts in the creation of a trophy trout

stream Waters Creek, the Chatta-

hooch~e Chapter of Trout Unlimited

was recently awarded the Gold Trout

Award as the nation's outstanding

chapter of TU. Formal presentation

of

the

award

was

made

by .Chris

Colt,

/

Southeastern Represe ntative o f TU

National , at the chapter's annual fall

banquet held in Atlanta.

Michael Frome, Conservation Edi-

tor of Field & Stream, was the guest

speaker at the banquet. Chris Colt

also presented Mr. Frane with the

well deserved TU Gold Trout Award

in the news media category

Joe Townsend presented the Chat-

tahoochee Chapter's Silver Trout

A ward in the professional category

to Leon Kirkland, Chief of Fisheries

of the Game and Fish Division, Geor-

gia Department of Natural Resources,

for his outstanding contributions to

trout fishing in the Southeast and the

State of Georgia during the past 15

yea rs.

Herb Beattie, President of the

Chattahoochee Chapter, presented

the Ch apter's Silver Trout Award in

the non-professional category to Kirk

Johnson of Chattanooga, Tennessee,

"mister" Association for the Preserva-

tion of the Little "T " Kirk was rec-

ognized for his fight to save the Little

Tennessee River.

Bill Surls presented the Biggest

Trout Released Award to Bo Brooks

for his 26-inch brown caught and

rel eased in Waters Creek. There is

a strong possibility that Waters Creek

will yield a 30 inch trout to take the

contest next year.

-Joe Townsend

Sportsman's Calendar

FOX: There is no closed season on the taking of fox. It is unlawful for any person to take or attempt to take any fox, within the State, by use or aid of recorded calls or sounds or recorded or electronically amplified imitations of calls or sounds.

GROUSE: October 14 through February 28. Bag limit 3 daily with the possession limit of 6.

WILD HOGS: Hogs are considered non-game animals in Georgia. They are legally the property of the landowner, and cannot be hunted without his permission, except on public lands. Firearms are limited to shotguns with Number 4 shot or smaller, .22 rimfire rifles , centerfire rifles with bore diameter .225 or smaller, all caliber pistols, muzzle loading firearms and bows and arrows.

Night hunting allowed. All counties south of the above named counties are open year round for the taking of opossum. No bag limit. Night hunting allowed.

QUAIL: November 20 through February 28. Statewide season. Bag limit 12 daily with the possession limit of 36.

RABBIT: November 20 through January 31 in the counties of Carroll, Fulton, DeKalb, Gwinnett, Hall, Habersham, and all counties north d;f those listed. Bag limit 5 daily November 20 through February 28 in all counties south of the above listed counties. Bag limit 10 daily

RACCOON: October 16 through February 28 in Carroll, Fulton, DeKalb, Gwinnett, Barrow, Jackson, Madison, Elbert and all counties north of those listed . Bag limit 1 per night per person. Night hunting allowed. All counties south of the aboe named counties are open year round fm the taking of raccoons. No bag limit. Night hunting allowed.

SQUIRREL: November 4 through February 28. Bag limit 10 daily

OPOSSUM: October 16 through February 28 in Carroll, Fulton, DeKalb, Gwinnett, Barrow, Jackson, Madison, Elbert, and all counties north of those listed. No bag limit.

TURKEY: November 20 through February 28 in Baker, Calhoun, Decatur, Dougherty, Early, Grady, Miller, Mitchell, Seminole, Thomas Counties. Bag limit 2 per year

C>utdoors

iQ ~ee~r~ia

Send check or money order to:

2/73

Outdoors in Georgia Magazine

270 Washington St., S.W., Atlanta, Go. 30334

Check one

0 RENEWAl

Paste your last magazine address label into space indicated and mail with payment.

0 CHANGE OF ADDRESS

Paste recent magazine label into space indicated, show change on form and moil.

0 NEW SUBSCRIPTION

Fill out form at right and mail with payment.

0 GIFT SUBSCRIPTION

Show recipient's nome and address in form , indicate gift signature ond moil with payment.

Attach recent magazine address Iobel here for renewal, change of address, or inquiry.

Name

Address City

Stole

Zip Code

Sign Gift Cord

0 1 year $3.00

CHECK ONE:

0 2 years $5.00

0 3 years $6.00

Some Ja)' tbe norld will end 111 fire, Some Jay in tee. From 11bat 1'11e ta.rted of deJJre I nould bold witb tbOJe nbo jal'Or fire.

But 1j it bad to pensb tnice,

I tb111k I knoJJ' enougb of bate

To .ray tbat for destructJOil ICe Ir also great

And Jrould mffice. Robert Frost